“I want to clarify - it was a bandana, not a durag,” Dante Ross says with a laugh. It’s an inside joke about our time spent with Dante in the studio, and how when he brought out that durag, I mean bandana, it was a sign of serious business.

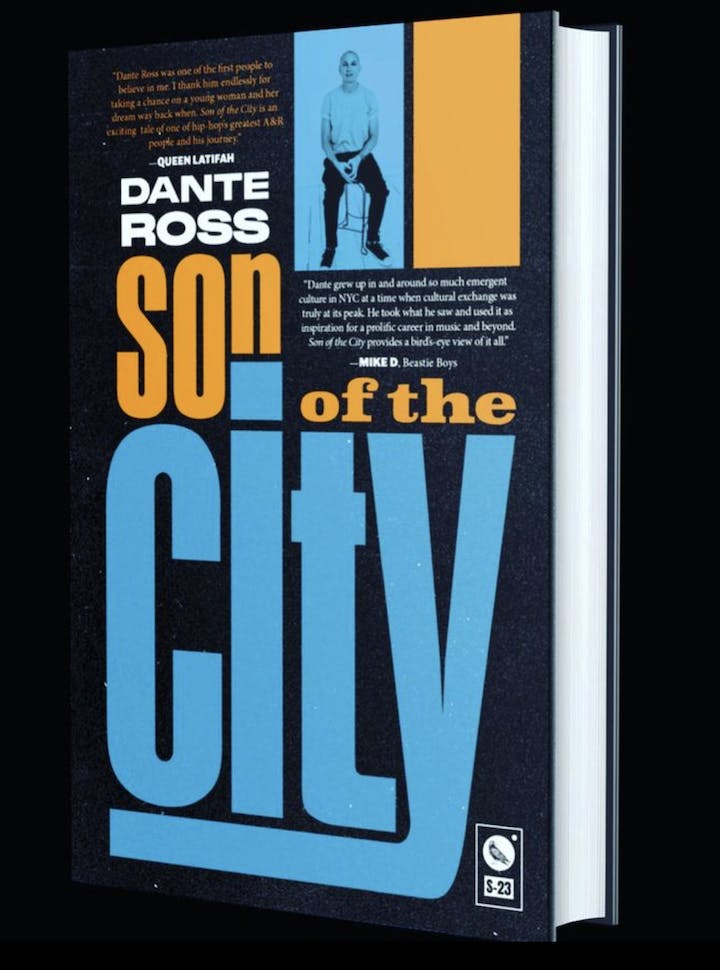

Dante has reason to smile. It’s a bright and sunny day and he is just weeks away from the release of his new memoir, Son of the City. We are towards the end of a long and thorough conversation — centered around how the book travels through his upbringing, music career, and his sobriety — through candid reflections and critical social commentary.

Donned in a Marvin Gaye hoodie and camo hat, he is sitting comfortably and waxing poetic about the notion that his whole life is about to become common knowledge.

“It's a little daunting because now the whole world's gonna have the book," he says. "I'm kind of under a microscope a little bit, which is a little scary. My biggest concern is selective memory. I did my best to avoid selective memory, but I think it's inevitable when you write a memoir.”

It is very easy to get selective memory in the music business. It’s a space that moves very quickly, and very much lives by the adage, “what have you done for me lately?” Additionally, accountability is not easy, and writing about your wins is always more fun than re-living and sharing the losses.

Where many memoirs keep character flaws to a minimum, 'Son of The City' puts them out in the open.

While he could have solely focused on his adventures in Hip Hop, he purposefully chose to pull back the curtain and show the struggles he and his family endured as a child growing up in New York City.

“I think you have to know how I was raised and what I dealt with growing up to understand why I behave the way I behave, and why I pursued the stuff I pursued, good and bad,” he says. “[My] life wasn't necessarily easy, but it wasn't tragic either. And I want to be clear about that. My life was certainly unorthodox but also a real blessing. I think I had to get sober to really understand a lot of the pluses and minuses and really get over my anger and the chip on my shoulder, which to some extent still exists to this day. But I have the tools to pick it apart. I have the tools to be more contemplative and understand why I behave the way I behave.”

He started the book as a co-writing project with his father, the writer, activist, and organizer, John Ross. Unfortunately, Ross’s father was diagnosed with cancer and passed away before the two could execute their idea. Rather than give up the idea of writing a book, he turned inward and created a memoir that looks back at an exceptional life and a career spent spotting talent, developing that talent, and then doing whatever it took to amplify that talent.

His catalog as an A&R and/or producer can rival any of his peers and includes Golden Era beloveds like Brand Nubian, groundbreaking trendsetters like De La Soul, underground heroes like MF DOOM, and bonafide superstars such as Queen Latifah and Busta Rhymes. Not to mention, 3rd Bass, Santana, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, House of Pain, Del The Funkee Homosapien, Everlast, Lil Dickey, and countless others.

“It’s funny to be the artist for a change,” he tells me. “For me it was important, not to be fatalistic, but we don’t live forever.. It’s good to know that I got it all down. I got it on paper before my time’s up. I got something that will preserve my space in the culture. It’s my marker. It’s important to me. I did that. It’s an accomplishment and it feels good.”

I was able to talk with Ross ahead of the book’s release and an upcoming book tour that will see him criss-cross the country discussing his upbringing, his entrance into Hip Hop, and a career in music that spans 5 decades and countless shifts in the sound, style, and delivery methods of the music industry.

Alexander Fruchter: You are pretty open throughout the book about your faults and shortcomings. You write several times about your ego getting the best of you, or your temper getting the best of you. In a lot of music industry memoirs the author's faults are few and far between. Yours are centerstage, and working through them is a plotline. Did you plan to do that from the beginning?

Dante Ross: That was always part of it. My dad was a writer, and when I started the book, I was going to write it with my dad, but he got sick and he passed away eventually. I don't think my dad would have allowed me to write a book with him that was shining, bright, and happy all the way through, so I kind of walked into it knowing that wasn't going to fly. I read all the time. I don't like books where things are always super — when it's all wins. If there's not a dynamic of up and down, why would I read this story? Why would I want to finish this book?

All the great books I grew up reading, and all the great books I've run across the last 20-30 years all have a dynamic of honesty in it. Whether it's John Fontaine or Flannery O'Connor, or anybody that I love, there's always some kind of up and down dynamic. And by no means do I want to sound pretentious, but I think about books like J.D. Salinger’s Catcher In The Rye, steeped in failure and the greater existential question of what is it really all about? That greatly affected me when I read it at 11 or 12 years old. I've always tried to write, and been a fan of writing that has a notion of honesty to it. I have a friend of mine that's a screenwriter, Seth Rosenfeld, and when I talked to him about writing my book and stuff, and we have another friend who wrote a book that I'll leave nameless, and Seth said, "Whatever you do, don't have your book be like so and so cause if you're the superhero that wins all that time, it's not a good fucking story." And I was like, "Point taken."

Alexander Fruchter: Towards the end of the book you question if it will ever be published, and imagine reading this very personal material in a room full of strangers. How does the reality of knowing both may come true make you feel?

Dante Ross: It's a little daunting cause now the whole world's gonna have the book. I'm kind of under a microscope a little bit, which is a little scary. But I'm sure I'll take it as it comes. I'm trying not to think about it too much, I'm just trying to put my best foot forward and see where it ends up. My biggest concern is selective memory. I did my best to avoid selective memory, but I think it's inevitable when you write a memoir. When you look back on your life, there's points and times when selective memory comes into play and I really tried to challenge that, but you never know. There's this book, The Night Of The Gun, and the whole book is about selective memory in a sense, and I tried to think about that book when I was writing this.

Alexander Fruchter: This idea of writing the book with your dad was the starting point. The book ultimately became different than that. Beyond just your relationship with your dad, you spend a lot of time writing about both of your parents, their faults, your siblings, finding out that you had siblings you didn't know about. Was it important to get those family stories out? You could've written this book just about your music career without talking about your family at all and it would've been a lay-up. "Let me write about the Beastie Boys, De La Soul, getting yelled at by Lyor Cohen, and I'm good to go." How important was it to shed light on how you grew up?

Dante Ross: It was really important because that's the stuff that shaped me. There's a cathartic thing that goes on when you write about your childhood and your life as opposed to just the bells and whistles. I think that lent the book, and lends my story some humanity. I think you have to know how I was raised and what I dealt with growing up to understand why I behave the way I behave, and why I pursued the stuff I pursued, good and bad. I grew up with a lot of dysfunction, and I've preceded at various times of my life with some sort of dysfunction. So, I think it's important to tell the story as to why you operate the way you do. Life is not simple, and certainly my life is not simple. So I wanted to explain myself and in doing that I had to explain my childhood.

Alexander Fruchter: You write, "For a good deal of my life, I was pissed off I grew up the way I did." Later in the book you are thankful for the way you grew up because it allowed you to relate more to artists and exist in Hip-Hop as a white guy from New York City. At what point did you see or notice that and get past it?

Dante Ross: I noticed it early on - multitiered. One, the records that people were digging for and using for breaks, I knew all those records. So I knew them as a kid because they played them at the block parties growing up, and my sister played those records. I knew “Apache” and “Bra” and “Joyous” by Pleasure. I knew all these records cause these were the records I grew up hearing in the street.

I noticed it early on when I'm listening to De La Soul's record and I know all these samples because I grew up with all these samples. And even prior to that, going to clubs like The Roxy, they played records that I knew about. My exposure to records truly came from my childhood and where I grew up. And I think it was a blessing growing up how I grew up because I was never uncomfortable being the one white guy in the room. That never meant shit to me cause I was often the one white kid in the room growing up.

I grew up in a largely Puerto Rican neighborhood and that's just how it was. I never really paid any mind to it. It never felt any different to me. It felt like my childhood was great training for my A&R career. It also made me tough. I'm a resilient character, and that's because of how I grew up. Life wasn't necessarily easy, but it wasn't tragic either. And I want to be clear about that. My life was certainly unorthodox but also a real blessing. I think I had to get sober to really understand a lot of the pluses and minuses and really get over my anger and the chip on my shoulder, which to some extent still exists to this day. But I have the tools to pick it apart. I have the tools to be more contemplative and understand why I behave the way I behave.

My life the last 12 years has been a lot of unpacking of childhood trauma, PTSD, life experience, and accountability. As I got older and got sober, it got a lot easier to be accountable and the only way you can make peace with your past is to be accountable. I think that the book is an examination of some of that.

Alexander Fruchter: You talk a lot about your parents’ struggle with drugs and alcohol, as well as your own. And you talk about your own movement to get sober. How much have drugs and alcohol influenced your life, directly or indirectly, both the presence and now the absence of them?

Dante Ross: I think immensely. It was weed. I'm not a daytime drinker, but weed certainly navigated a lot of my behavior. I had been a daily pot smoker since I was 14 or so. I got sober at 44. It was a longtime. A fucking long long time, 30 years of smoking almost daily with a few intervals of not. Drinking on the other hand, I was not a daytime drinker, but drinking certainly navigated my social behavior. I was beyond a social drinker. Every time I went out and had one drink I had 10. Even when I was not drunk, being hungover will affect your behavior greatly. It definitely was a component in my life and behaviors. And I think for a lot of people it is. And me being sober makes me no better than anyone else. It just makes me someone who has to be more accountable for the fucked up shit he might do, or less likely to do fucked up shit because I am accountable and conscious and aware. It's not for everyone and I don't judge. Lots of people can smoke a little weed here, have a drink there, have a glass of wine at dinner. I have tons of friends that can do that. I personally couldn't do that, so I had to change the way I was living my life.

Alexander Fruchter: Going back to what you just said about how you grew up, there's another quote I wanted to bring up. You wrote, "It's one thing to study multiculturalism in college, it's another to live it." You talk a bit about race throughout the book, one chapter in particular using the Rodney King riots as a starting point. You observe that you and your friends grew up in the same neighborhood and how your friends that were not white, how their lives went versus your own. I thought that was interesting and also I could identify a bit with that growing up on the southside of Chicago in Hyde Park. It was not Manhattan’s Lower East Side, but had some similarities and I am familiar with being the only white person in the room. You write about the urban white kid, where I think when we think of white rap fans, we're thinking of frat parties and suburban kids trying on Hip- Hop for a little bit and then getting rid of it. Your book sheds a little bit of light on an experience that might not be thought of or noticed.

Dante Ross: It's funny. I never want to be like, "I'm the funky white boy in the room." That shit's corny to me. I never cater to that or romanticize that. There are people out here that do that and I don't think it's necessary. I never tried to be anything other than what I am and who I am. And what I am is a kid who grew up with a blue collar in a Puerto Rican neighborhood and that shit shaped a lot of my experiences.

I didn't really know white culture or what people would deem white culture until I got a little older. I was lucky to go to an academically accelerated school on the west side in the West Village. I grew up on the Lower East Side. So I went across town to a nice neighborhood and I experienced a different form of life. I saw people who didn't have to worry about some of the shit I did. It said to me, "There is another world out there, that's not necessarily your world."

I think because my mom was an academic of sorts, and a hippie, she exposed me to a lot of stuff. And those things I was exposed to helped me have a much fuller life than some of the people I grew up with, unfortunately. They didn't have the same exposure level even though our economics were similar.

Because I am white, whether I want to say it or not, truth of the matter is, I've been granted some form of white privilege.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

If I don't cop to it and examine it, then I can't effect any change that encompasses white privilege. I have to acknowledge it. And there was a point in my life when I thought it was all ubiquitous. My dear friend Paul when I was like, "Yeah, I don't see color,' he was like, "Yeah, cause you're fucking white." I was like, "Oh shit, my man's completely correct. I don't see shit because I want to live in this fucking bubble. But that bubble is bullshit and if I was Black or gay or Asian or whatever, "other," I would certainly not feel that same way.’

I had to examine and re-examine some of the ways that I thought about things. I'm always cognizant of that. I think now the Hip- Hop experience is, "Look, every white kid loves Hip-Hop for a couple years." That's part of life. There's nothing wrong with that, but for me it was never an option to just try something on for a few years. It really is a deep part of my life.

Alexander Fruchter: Switching gears to the music stuff. One of the great quotes in the book is, "Sometimes in this game, you gotta be a hustler." How much of your success do you consider talent vs. your hustle and putting yourself in the right places?

Dante Ross: I think it's both. When we talk about talent, my talent is finding talent and seeing talent in others. Sure, I produced some records but I was never the world's best record producer. I have no illusions. I was not Q-Tip. He's fucking amazing. I'd seen him work and many others. I had no real illusions as being that.

I have really good instincts. And I have really good taste, and that's my talent. I can see talent in others, and I have pretty good taste. And I still have good taste to this day. That's my talent. My hustle is: I'm relentless. I didn't grow up with a silver spoon, there's no nepotism in my story, so I had to fucking hustle. So I hustle.

It's a fine balance between the two. As I got older, and it's not so easy to admit this, some of the hustle is survivalism. As I did A&R at my last little run at ADA, I had to find things that I thought would move because I had to keep a job. I had a mortgage and bills, I had all this stuff I had to deal with so I had to involve myself maybe in some stuff that in 1992 I wouldn't have signed or done. But the culture shifted a lot and those aesthetics were harder to embrace in the environments that I was working in. So it's part hustle and it's part instinct and it's mostly integrity. You always want to move with integrity and you don't want to lie to yourself. I have to compartmentalize things. I have to know what everything is for, what it is. No knock on Lil' Dicky, but I have to know what Lil' Dicky is. He's not Brand Nubian or Rakim. He's not MF DOOM. And I know this. I have no illusions. It's hustle, integrity, and honesty. Being honest with yourself and being adaptable.

If you're not adaptable, you will not survive in this business.

Alexander Fruchter: As I was thinking about the book and prepping for this interview, I started to see that some of the struggles and behaviors you are talking about in your life were also being mirrored through some of the artists. It's like you used the artists in contrast to each other and yourself. In one sense you say that Grand Puba could've been one of the best but he got lazy and comfortable and didn't have that outcome. In the same period you write that Busta Rhymes is the most driven artist you've ever worked with.

Dante Ross: He is. Look at where Busta is today. He had a battery in his back his whole life. I don't know what the reason is, but the guy is relentless. He wants to fucking win and he's won really big. He's always been super talented and always been driven. Master politician. Don't give him a feature cause he's gonna fucking smoke you. Busta said this to me, he looked up to Puba. He was at Elektra when everyone was like, "Puba, Puba, the God." But Busta put that shit in 5th gear and fucking passed him.

Look man, you can never fucking tip your hat to a guy like Busta Rhymes enough, or a guy lie Diddy for that matter. Some guys are just driven. And Puba wasn't driven. In my own life, I'm not that driven. Probably I have been over concerned with integrity over being driven. Hence, I've been the senior VP at a bunch of labels, I've never been the president.

Alexander Fruchter: I want to stick to the subject of groups. Some of your first activities are with the Beastie Boys. You weren’t part of the Beastie Boys, you didn’t manage them, but you were working with them, you were exposed to opportunities and then the first group you A&R’ed is De La Soul.

Dante Ross: In a weird way, and although I’m not credited, unbeknownst to me, I helped A&R 3rd Bass. It was by accident. They were my friends. Sam Sever was my friend. I put them together. I would say De La Soul is my first accredited job.

Alexander Fruchter: So you have Beastie Boys, you have De La Soul. These are two groups that make classic music. Beastie Boys are in the Rock N’ Roll Hall of Fame, I can envision De La Soul being there. They certainly deserve to be there.

Dante Ross: They’ll probably end up there one day.

Alexander Fruchter: I am a big fan of both these groups, maybe it happened behind the scenes, but there was never a public rumor of Ad-Rock having a solo album, or Mike D. with a solo album, or Posdunous’ solo album coming… There was never talk of that. You contrast those groups with Brand Nubian, L.O.N.S, some of the groups that disbanded and their egos got in the way. What do you think is the difference between Beastie Boys and De La Soul — groups that have never broken up — versus 3rd Bass, House of Pain, Brand Nubian…

Dante Ross: That’s a really good question. I think it ultimately comes down to mutual respect. And giving each other enough space. Beastie Boys made millions and millions of dollars but lived pretty humble lives. They never bought fancy sports cars, it never was rock n’ roll fantasy for those guys. They were grounded people. And De La as well.

I think it comes from their values, their aesthetic, and their mutual respect for each other. It’s a reflection of their values. Those guys were all raised pretty well, they’re all pretty evolved people, and I think they all gave each other enough room to say, "Hey, make a mistake if you want to make a mistake," or, "Live your life how you want to live your life." And I think the other groups maybe didn’t do that.

House of Pain is the exception. They weren’t quite as successful as the Beasties or De La. The Beasties are uber successful. When you’re that successful, I think it should make it easier to navigate things. It doesn’t always. The Paul’s Boutique thing was a real testament to their character artists and they sailed right through it perfectly. And De La too for that matter. De La has this huge first record. The second record is called De La Soul Is Dead. It’s like, "We’re going to shoot the myth of who we are and murder it and we're gonna do this, we don’t care if we have a hit record." It’s almost like they didn’t want a hit record. But, if they hadn’t done that, they might have self-destructed.

Both of these groups’ second albums are very important in the trajectory of the rest of their career. If Beastie Boys don’t do Paul’s Boutique, and it doesn’t flop, they don’t have the balls probably for Check Your Head, because they had nowhere to go but up. To people like me and you, that record’s great. But when Paul’s Boutique came out motherfuckers were like ‘huh?!’

Alexander Fruchter: It’s got a few songs on it…

Dante Ross: Like I said, it’s got two songs on it. And I said that as an A&R asshole, not as a fan of the record. It didn’t have hit songs. There was no fucking “Fight For Your Right To Party.” And if you listen to that De La Soul record, De La Soul Is Dead, there’s no “Me Myself and I.”

I think that those commercial stumbles, because artistically those records are brilliant, really helped these groups evolve and it gave them the space to become who they are.

3rd Bass was put together as a group. They weren’t life long friends. I could see why they broke up. House of Pain wasn’t built to last. They had massive success and never repeated that massive success. I think resentments evolved because of it.

Brand Nubian, Grand Puba was probably always looking to a solo record and was always a pretty self-centered person. If you listen to their first record, he has solo records on the first album. My biggest regret with that is, he didn’t need to quit Brand Nubian to do a solo record. And L.O.N.S. were also assembled by Spectrum City, Chuck D and the Bomb Squad, so they also didn’t have this lifelong friendship, and I think that’s part of the reasons that all of these groups broke up.

When I look at De La, they have been friends since high school. They grew up together. Beastie Boys have been friends since 9th grade or something. There was a mutual love and respect for each other that maybe those other groups didn’t have or not the same level.

Alexander Fruchter: It seems like throughout your career you worked with groups that were starting to form or starting to transform. Looking at MF DOOM, you worked with him and Subroc in KMD and then he had to reinvent and came back as MF DOOM. Everlast is first with Ice T, then with House of Pain and has huge success, and then that’s over and he has to reinvent and he comes back as Whitey Ford. In your own ups and downs, did you ever look at these guys as inspiration? Did you ever put it together like that?

Dante Ross: Sure. 100%. I looked at the Beasties as well. Paul’s Boutique comes out and people are like, ‘What happened to your boys?! What happened to your friends?" I’m like, "Go fuck yourself." And then they come back and they fucking come out swinging and fucking take over again. To me, that was always kind of inspirational. It’s funny, them and Rick, though not really older than me, in fact Ad-Rock is younger than me, I was always inspired by those guys and all they did.

Life is a long long game and so is your career if you’re smart. DOOM was certainly inspiring. Jesus christ, his reinvention was legendary. Though I don’t think necessarily embraced by the people who embrace him now, all the so called DOOM fans that probably never listened to him til he died, your favorite rapper’s favorite rapper. I think reinvention is always fascinating. David Bowie was probably the best rock thing in the 70’s and his constant reinvention was amazing. And then you look at Prince, his reinvention throughout his career and others, the Beatles for sure. Being able to reinvent and transform yourself musically is always fascinating to me. I love when bands do it. Even Radiohead did it and De La did it in a sense, the Beastie did it. It was inspiring. I would say certainly with Everlast, the Beasties were part of the inspiration. The fact they picked up instruments and did this thing, it was like, ‘oh, you can really think outside the box and do whatever you want.’

Alexander Fruchter: Time and time again in the book you bring up the term “Record Men,” and that being called a “Record Man” was a big thing for you. Was that always a goal for you? Do you think Record Men exist anymore?

Dante Ross: I think they do. Few and far between. Now it’s like analytics and research, not A&R. And I think I want to say Lyor is the first person I ever heard use that term. I remember he and Russell tried to hire me and eventually I did a deal with them, but when I turned them down they told me I had become a Record Man. And they were like, "You’re a real 'Record Man.’: And I was like, "Wow, that’s cool." And you know, a Record Man is a Bob Krasnow, a Seymour Stein, Diddy for sure, Matty C, Steve Rifkind. You don’t necessarily have to be an A&R guy, but you have to understand the cultures moving around you and be cognizant of it and know that you don’t know everything. These are people who are Record Men. Is the regular kid that does A&R now a Record Man? I don’t know. Maybe yes, maybe no. Mike Karen is a record man, love him or hate him. Orlando Whartonberg. There are guys out there who are Record Men, Craig Kalman, etc… It still exists. It’s not a requirement for the job anymore and I think that that style of record guy is going going gone.

Alexander Fruchter: One person you mentioned throughout the book in very positive ways is Steve Rifkind.

Dante Ross: Love Steve Rifkind

Alexander Fruchter: Hip-Hop is now 50. You’re finally seeing where artists have aged and a certain section of artists, and the executives and people around them have also aged well. They’re not desperate or trying to appeal to young fans, they’re really just aging with their original fanbase. Steve Rifkind is having a new moment right now. I’m wondering how it feels to see that Hip-Hop is now 50, and not just the artists, but people like Steve getting flowers, getting opportunities and saying, "We don’t have to cater to anything, we’re going to our thing this way."

Dante Ross: Steve’s a dear friend of mine. His personal evolution in the last 5 to 10 years has been pretty transformative and I believe where he is career wise is reflective of that. I think Steve, like me, challenged himself in a lot of places. I think psychologically, mentally, physically I think he’s transformed a lot of himself in a positive manner and been pretty upfront about it and incurred a new sense of self-awareness and gratitude and I think what you’re seeing is reflective of that. He’s always been a gracious guy, like a really loyal person. Super loyal, fiery, and I think he's a little less feisty than he was before. He’s evolved a bunch like all of us should when we get older. It’s nice to see. I’m working on a project with him. I can’t really talk about it, but I’ve been working on it for awhile, it’s really cool to see where Steve is right now. It’s inspiring.

Alexander Fruchter: You mention in the book that outside of Charlie Brown from L.O.N.S., the artists that you’ve worked with or signed, none of them speak ill of you, some of them gave you quotes for this book. How does that rank in your achievements alongside the record results and the music? It seems like that’s even higher or makes you more proud.

Dante Ross: Yeah, it is. Because that’s forever. You know that you did the right thing for these artists by protecting their vision, their integrity, supporting them and by being in trenches with them. That’s invaluable. For me, those props are the highest level of it all. For the most part, all the guys I logged time with in the earlier days are still good friends of mine. Whether it’s Busta or Queen Latifah, I stayed friends with all of them. That stuff means a lot. And the inverse of that, the artists I signed in the last decade, decade and a half, I didn’t have those close bonds with them. I didn’t spend quality time in the studio with them. That’s not the process anymore. So, and maybe because I worked at a distributor, it’s a little less hands on, I didn’t have those experiences with those guys.

Alexander Fruchter: How does this time period feel? The time between being done with the book and waiting for it to come out. You talk about this time period a lot in the book. You knew you had a hit record and just had to wait for it to come out, what’s this in between time like for your book and how does it compare to when you were A&Ring and waiting for these projects to come out?

Dante Ross: It’s a little daunting. Sometimes I joke and say I’m a struggle rapper on an indie label. I’ve come to find out that I have to do a lot of shit myself, and that’s cool. I actually talked to Bobbito like, "How do I do this?" Because he’s always done everything himself. So, it causes me a little anxiety. I’m curious to see what the reaction will be. I have a little excerpt coming out in Rolling Stone, which I got myself, which is really cool. That will be interesting. I gotta go to New York and do a bunch of events and then I come back to LA and do a few of them. And then I’m going to go see you and go to Seattle, the Bay Area, London. It’s interesting, I got a mini-tour coming up and I’m trying to get healthier.

I look forward to it. It’s interesting. It will be an adventure. It’s funny to be the artist for a change. It’s not my first rodeo. I’ve been through the roll out on a lot of records. I used to think it was like having a baby the first time. This brings me back to that a little bit. I’m never going to write another book. It’s not going to happen. I doubt it highly. So this is my one shot. For me it was important, not to be fatalistic, we don’t live forever. I lost a lot of people the last few years including my 2 SD50 brothers and guys like Keith Hufnagel, who I thought would never die, he’s indestructible, other people who passed. It’s good to know that I got it all down. I got it on paper before my time’s up. I got something that will preserve my space in the culture. It’s my marker. It’s important to me. I did that. It’s an accomplishment and it feels good. Whether I sell 43 books or lots of books, I already optioned the book for a film/tv project. I have lots of stuff surrounding it. Bobbito told me, "Yo, don’t worry if your book sells, it’s all the shit around it." And he was absolutely right.

See Queen Latifah and De La Soul perform at this year's Rock The Bells festival.