The Day After the Sedgwick Avenue Party

The Day After the Sedgwick Avenue Party

By Alec Banks

Published Wed, May 6, 2020 at 6:43 PM EDT

For most New Yorkers, August 12 was just a typical Sunday. The front page of the Daily News reported about Mickey Mantle’s homer off Whitey Ford during an old-timers game at Yankee Stadium. Number 7 was photographed circling the bases with a wide grin on his face, perhaps relishing in the bittersweet fact that legends, as they say, never die.

This day would also mark Hip-Hop’s slow ascent from its humble origins inside a rec room on Sedgwick Avenue to becoming a worldwide phenomenon — in which superstars like JAY-Z and Eminem could pack Yankee Stadium without ever having to don the pinstripes.

The recipe for Kool Herc and his sister, Cindy Campbell, remained the same at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue after their historic August 11 party. The rec room continued to be the epicenter for parties where people could listen to the “breaks” that Herc uncovered from “Uncle Nick” at Downstairs Records inside the 42nd Street subway station.

Their success coincided with the downfall of Bronx house parties. Since the Campbells’ version didn’t rely on waiting for someone’s parents to go out of town, they were much easier to pull off. However, as word spread about Herc’s prowess on the 1’s and 2’s, the parties became too popular too quickly. After a brief tenure doing all-ages shows at the Webster Avenue PAL, Herc notably threw a boat party for Cindy’s high school — an event he fondly recalled as his favorite party ever.

“At the time, ‘Rock the Boat’ [by Hues Corporation] had just come out,” Herc said in The Record Players: DJ Revolutionaries. “And the boat got ready to dock and the water got kind of rough. And then the boat is rocking like this and I put on ‘Rock the Boat.’ [Sings] ‘If you’d like to know it, you got the notion, rock the boat, don’t stop…’ and everybody starts running from side to side to rock this fuckin’ boat.

The captain, the teachers said ‘Yo! take it off. Take that goddamn record off. And that shit made the school newspaper.”

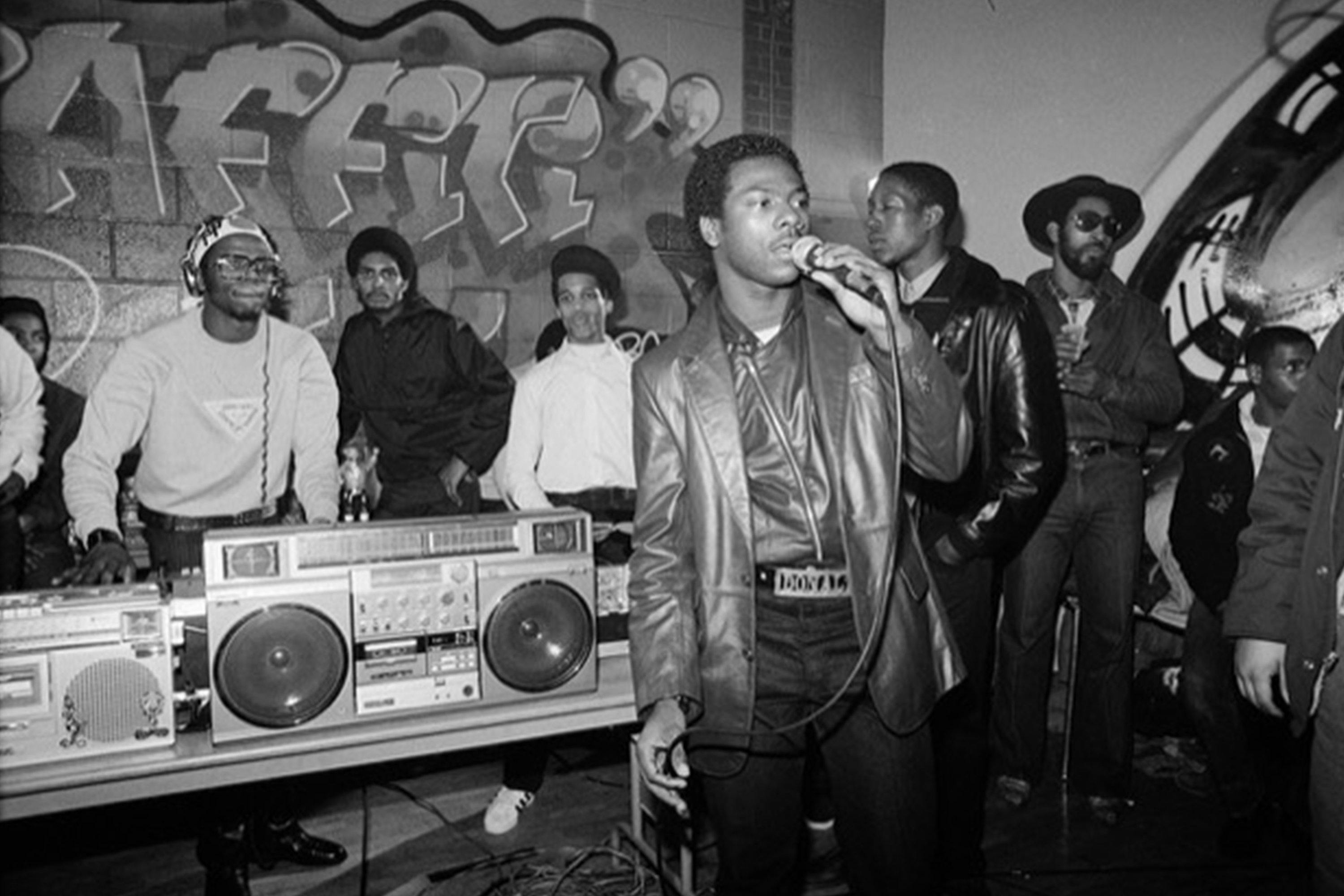

BRONX RIVER JAM / PHOTO: SOPHIE BRAMLY

Herc eventually took the parties outdoors to Cedar Park, where he tapped directly into the streetlights to power his booming “Herculoid” sound system. In May 1974, a young Grandmaster Flash saw a flyer for a show that would change his life forever: “DJ KOOL HERC and the Herculords return with…THE BAD MACHINE!!! SURE SHOCKER!!! With COKE LA ROCK and DJ CLARK KENT…a birthday celebration for…Wendy & Alvira. Saturday, May 25, 1974 CEDAR PARK REC CENTER 9:00 p.m.-??? 16-18 ONLY!!! I.D. REQ. Free admission…no guns—no alcoholic beverages—no drugs.”

“Cedar Park was almost all the way to the Harlem River and 10 blocks north of my house,” Flash recalled in his memoir. “But I was prepared to crawl there if I had to. It was late April and finally warm enough to be out all night in shirtsleeves, so I left the house in a little more than a tee, shorts, a Kangol, and sneakers.”

Flash heard Herc’s sound system before he ever laid eyes on him. He was still two blocks away when the bass from Babe Ruth’s “The Mexican” hit him in the chest like a mortar round.

“I had never heard sound — let alone music — that loud before in my whole life,” Flash said. “And though the speakers made the ground shake, I could hear the highs of the trumpets as clear as I could feel the boom of the bass coming up through my Super Pro Keds.”

As he got closer, he could see Herc. He sported a large Afro with a butterfly collar popping out of an AJ Lester leisure suit. Nearby, there were six guards who prevented people from peeking into his record crates or messing with his sound system — a perfect audio blend of a McIntosh amp with light-up displays, Gallahan subwoofers, and two Shure Vocal Master columns that covered the midrange. With a thousand watts per channel, the lights in Cedar Park would dim when the signal maxed out.

“It was the biggest phase of speakers I had ever seen,” Flash said.

Flash noticed how Herc was picking up the record needle and dropping it in the rhythm section on Coke Escovedo’s “I Wouldn’t Change a Thing” with little regard for the chorus or verses. Some records, like James Brown’s “Hot Pants” and Aretha Franklin’s “Rock Steady,” were familiar to him, while Baby Huey’s “Listen to Me” was completely new. Eventually, Flash would learn about Downtown Records and discover Billy Cobham’s nine-minute drum break on “A Funky Kind of Thing.”

Despite the Bronx’s reputation for gang activity, crews like Savage Skulls, Pearls, and Black Spades were side by side listening in peace. In total, 1,000 people — ranging in age from 4 to 40 — were sweating profusely as they pop-locked and breakdanced to Herc’s set.

“This cat had the scene locked down,” Flash said.

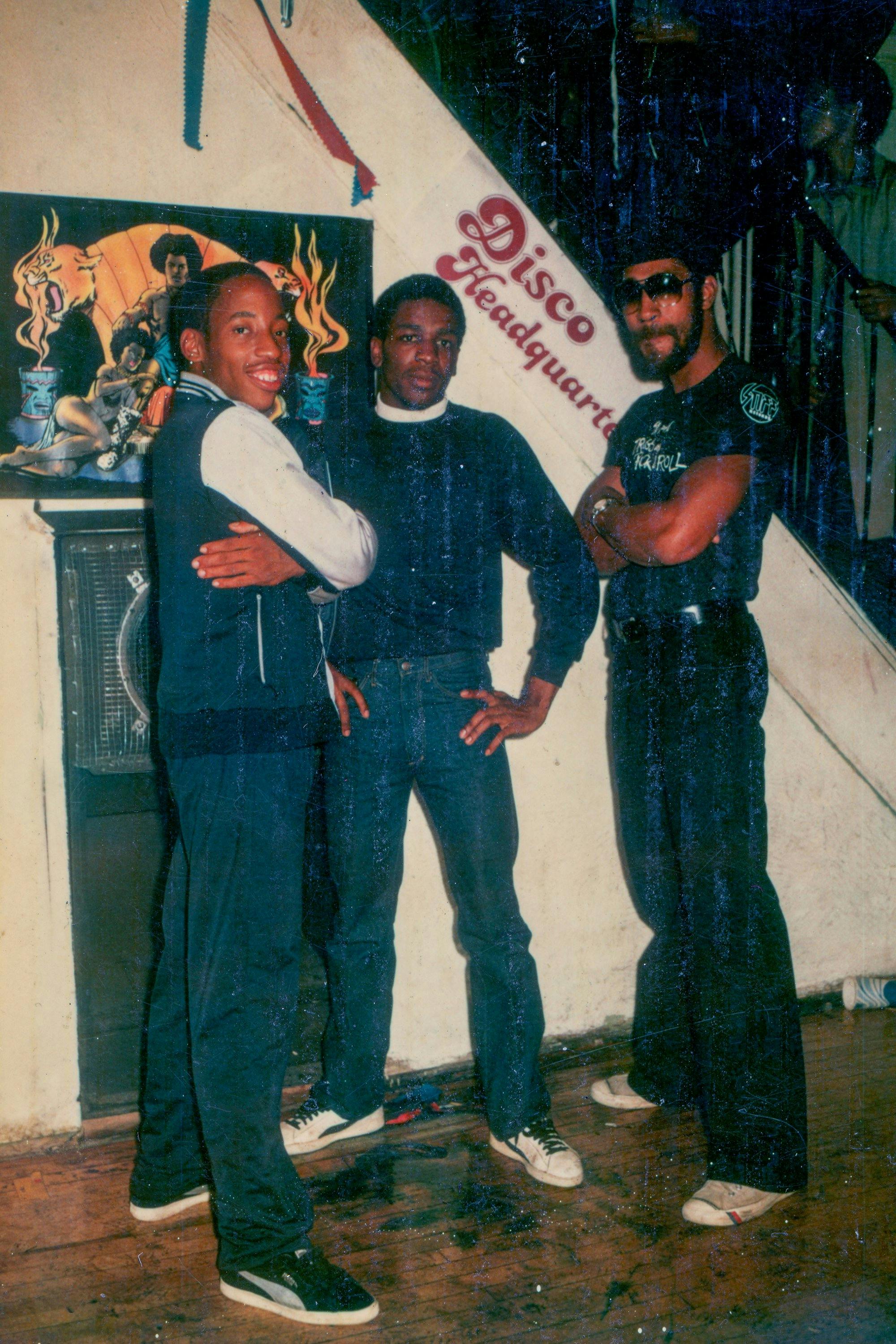

DJ KOOL HERC / PHOTO: JOE CONZO ARCHIVES.

The Cedar Park Jams were a Hip-Hop incubator — proof that this burgeoning musical movement was gathering momentum. But for the average New Yorker, they were simply an open fire hydrant on a hot day. Eventually, the temperature would change and people would head back indoors. Herc had to ask himself, “How do I keep the party going in an environment that exudes longevity?” He found his answer inside the Twilight Zone.

Located on Jerome Avenue, between Tremont Avenue and Burnside Avenue, the Twilight Zone was easily accessible to people via the IRT train, counting other clubs — like Soulsville/Hevalo and Hippie Campo — as neighbors. The space itself was hardly remarkable from the exterior. However, it was large enough to accommodate more people and gave Herc the ability to play boxing movies on a large screen using a Super 8 projector.

“The atmosphere at the Twilight Zone was just good people, it was elementary,” Herc told the Village Voice.

“When you were outside, waiting to see if you would get in, you had to come with it — if you got in it was about the way you speak, you got to be looking fresh, gotta be wearing the cologne, the high dress. It was maybe three, four dollars to get in. And keep it funny, keep it cool, and have a good time.”

While Herc’s initial connections to the Twilight Zone made him public enemy number one to the nearby Hevalo, the owners of that club saw him as an opportunity to make more money. Herc soon owned both the Friday and Saturday night slot at the Hevalo, where he played songs like the Whole Darn Family’s “Seven Minutes of Funk” and Johnny Pate’s “Shaft in Africa.”

“And it was there that we’d really start to see the dancers, the breakdancers in there,” Herc recalled. “I mean historically, this was Hip-Hop at the beginning and it was here that played a major part in it.”

Amongst the most noteworthy early b-boys/b-girls were Tricky, Wallace Dee, the Amazing Bobo, Sa Sa, Charlie Rock, Norm Rockwell, Eldorado Mike, and the [Expletive] Twins (later called the Legendary Twins), who performed what at the time was referred to as “Boying” and “Cork and Screw.” It was the Legendary Twins who eventually took the upright movements down to the floor — energized by Herc’s “Merry-Go-Round” technique, where he worked two copies of the same record, back-cueing one to the beginning of the break as the other reached the end, extending a five-second breakdown into a five-minute loop.

“When we used to go down on the floor, we didn’t get dirty,” the Legendary Twins recalled in the film The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy.

“We didn’t dance on linoleum, we didn’t dance on cardboards. We danced on the cement.”

While the connection between MC’ing, DJ’ing, graffiti, and breakdancing wouldn’t be examined in-depth until Charlie Ahearn released his film Wild Style (1983), there was an inexplicable link between Herc’s parties on Sedgwick Avenue, the Cedar Park jams, his sets at the Twilight Zone and the Hevalo, and an early organizational structure.

With the formation of the Herculords — consisting of Coke La Rock, DJ Timmy Tim with Little Tiny Feet, DJ Clark Kent, the Imperial JC, Blackjack, LeBrew, Pebblee Poo, Sweet and Sour, Prince, and Whiz Kid — Herc and company began highlighting both b-boy culture and early forms of rapping. For example, Coke La Rock would grab the mic and tell the crowd inside the Bronx clubs:

“There’s no story can’t be told, there’s no horse can’t be rode, a no bull can’t be stopped and ain’t a disco we can’t rock!”

Jeff Chang, author of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, said of the period after the Sedgwick Avenue party, “Many of the [Hip-Hop] pioneers point to that moment as a turning point in their lives and their neighborhoods. It was as if, by throwing their parties, they had given permission to a lot of other young folks to do the same. And so it went viral.”

As a result of Herc’s exploits, Hip-Hop was accessible to many. Grandmaster Flash eventually perfected a style of mixing so that breakbeats could be blended, Grandmaster Theodore invented the scratch, and Herc, Flash, and Afrika Bambaataa began residencies at the Bronx River Community Center, Black Door Club, and Audubon Ballroom.

By 1976, Herc was the most popular DJ in the Bronx. He acknowledged that he had competition, but he knew that he reigned supreme.

“We’re running this fucking Bronx,” Herc said. “You couldn’t throw a party on my night. I had guys had to change their dates if they found out I’m throwing a party on the same night.”

* BANNER PHOTO: PARK JAM / PHOTO: HENRY CHALFANT