There can never be enough beauty, let alone too much. —Zora Neal Hurston

The Cultural Legacy of Adornment

Zora Neal Hurston was a writer and cultural anthropologist who began her career reflecting on the rituals and mores of working people in Eatonville, Florida. She would spend time in and around the homes of Black Floridians often commenting on the colorful and ornate nature of these humble domestic dwellings. She mused on the idea of adornment, of dressing up even the most modest residence, and theorized that people of the Diaspora, perhaps, retain an impetus to decorate the body and abode in ways that stem from cultural lineage to African royalty and a pride and care in accounting for the beautiful.

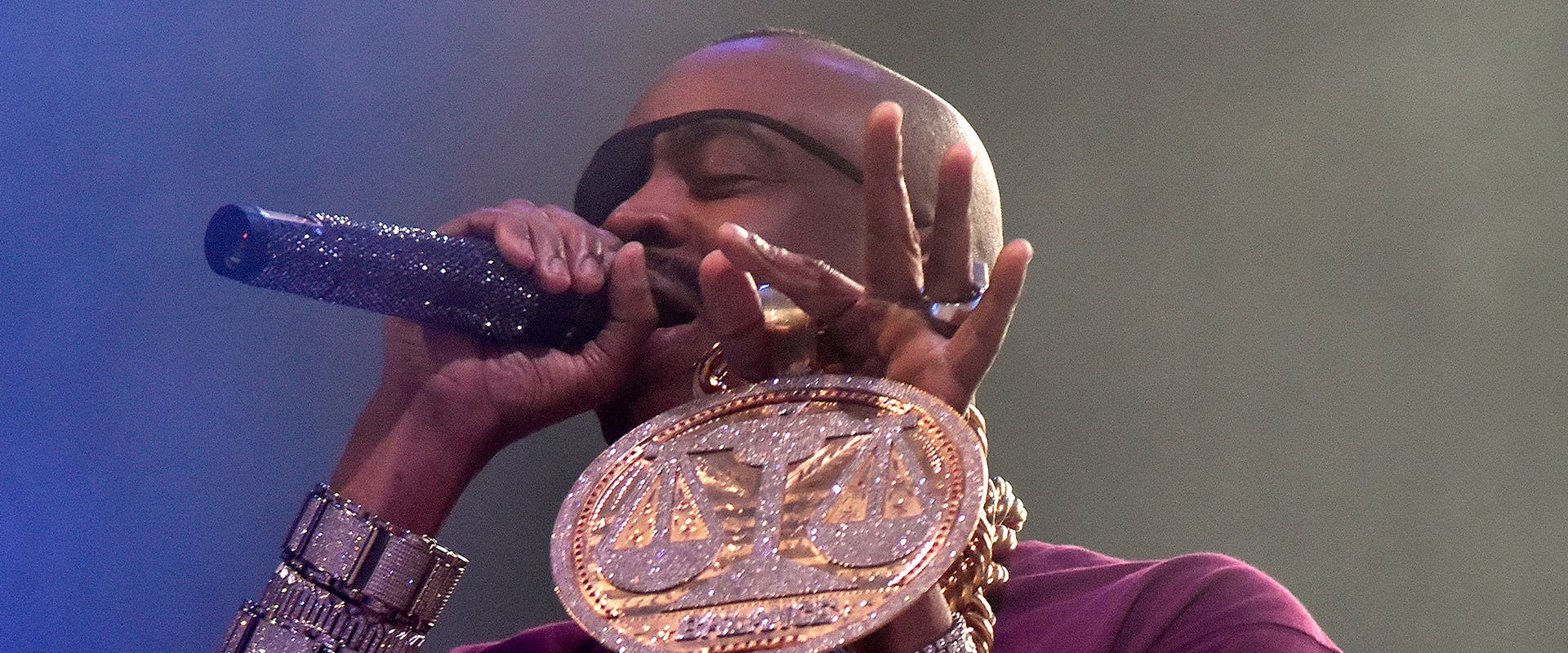

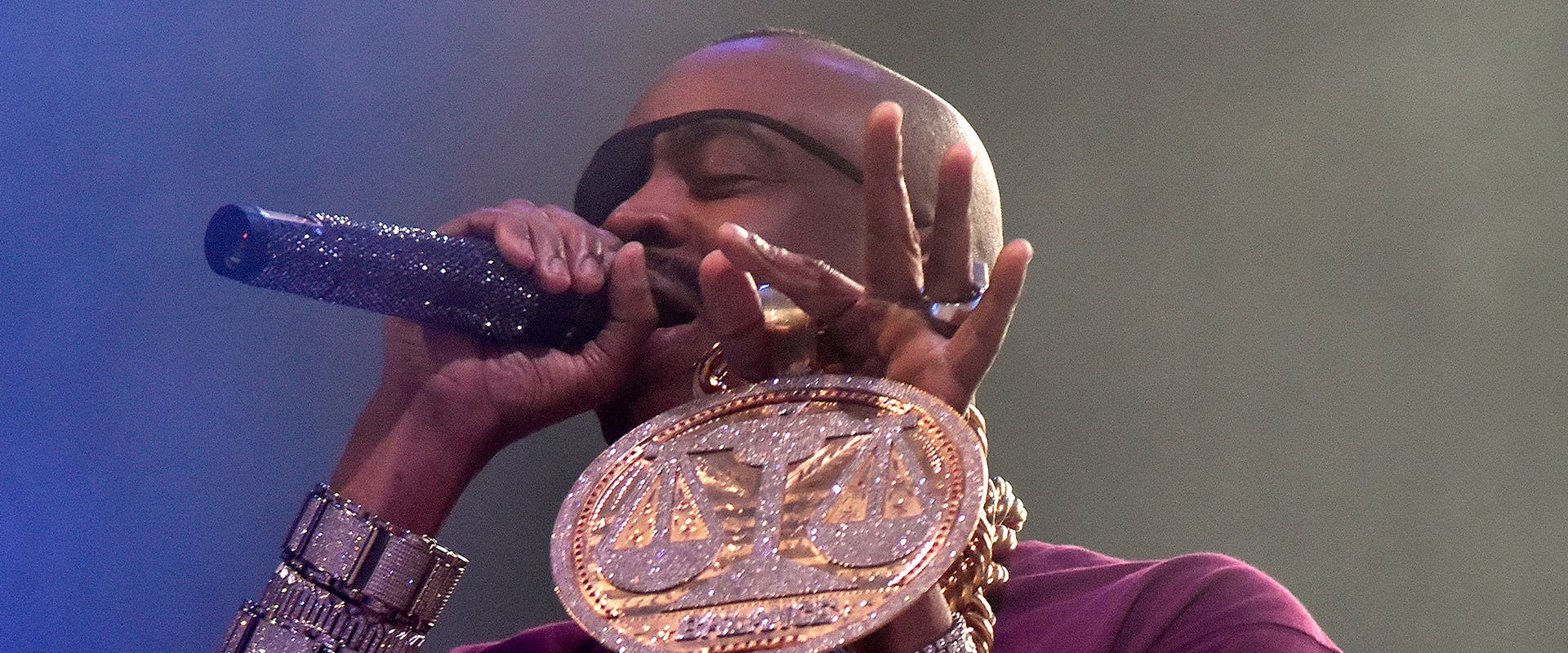

Hip-Hop of course is a Diasporic art form that takes this notion of adornment to loony tunes levels of brilliance and absurdity from Lil Uzi Vert's third eye pink diamond to 2 Chainz infinite Cuban links to LL's truck jewels. Hip Hop has stayed dipped in gold and jewelry. Now a billion dollar industry that has created generational wealth for some of its practioners, Hip-Hop has gone through stages of opulence to where the adornment of jewels is commonplace around a rapper's neck and wrist.

Labels have had their own chain as a signing bonus in certain instances. But it didn't start there. It was all a(n aspirational) dream. And there is no one, arguably, that brought the ostentatiousness and audacity and allure of adornment to the culture more than Slick Rick.

Hip Hop's Affair with Jewelry

Born Richard Walters, a Jamaican immigrant, whose family moved from The UK to the Baychester neighborhood of the Bronx in 1976, when he was eleven years old. While a student at LaGuardia School of Music & Art, Walters would notice the transformation of Fordham Road into an afterschool runaway. Kangols, Clark Wallabees, Ralph Lauren polos. Street entrepreneurs turned the block into a flip book of cool. Walters studied visual art in high school and was attuned to the vibrancy of styles, paying particular attention to the chains, bracelets and rings reflecting the sunshine and streetlights.

Walters became engaged in the nascent artistic form sweeping the boroughs and went on to start the Kangol Crew with Dana Dane. Soon after, he met Doug E. Fresh at a talent show and was asked to the join the Get Fresh Crew. Walters became MC Ricky D in 1983-84 and by the time his first solo album came out on Def Jam records in 1988, he was rebranded as Slick Rick. The age of the ruler, one of hip hop's greatest storytellers, was in effect. Slick Rick the name, comes from his accent and smooth delivery on the mic. A British inflection on record long before drill and grime, the emcee was signifying his cultural and colonial roots, flipping the monarchy upside down while notifying the culture of his stature. Ricky Walters became MC Ricky D who became Slick Rick the Ruler, a child king of England, and now the Bronx and West Indian diaspora.

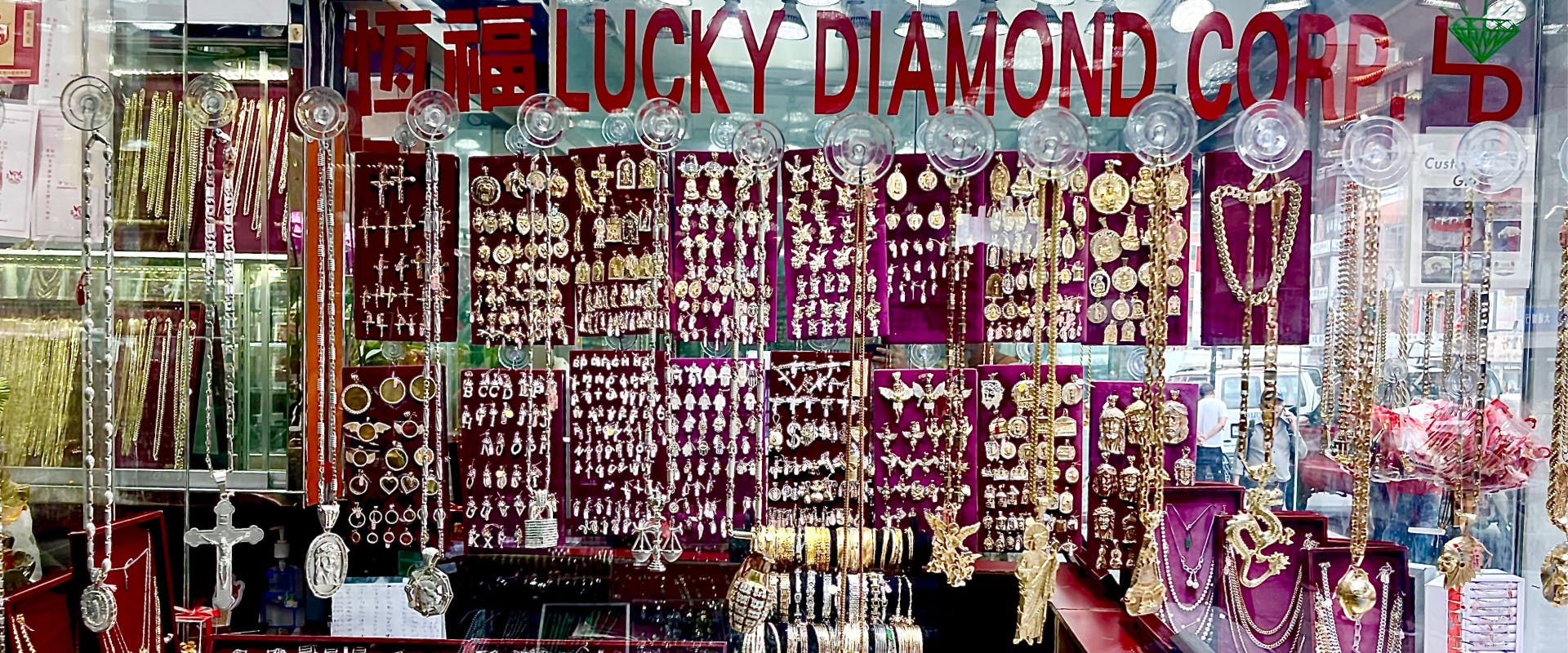

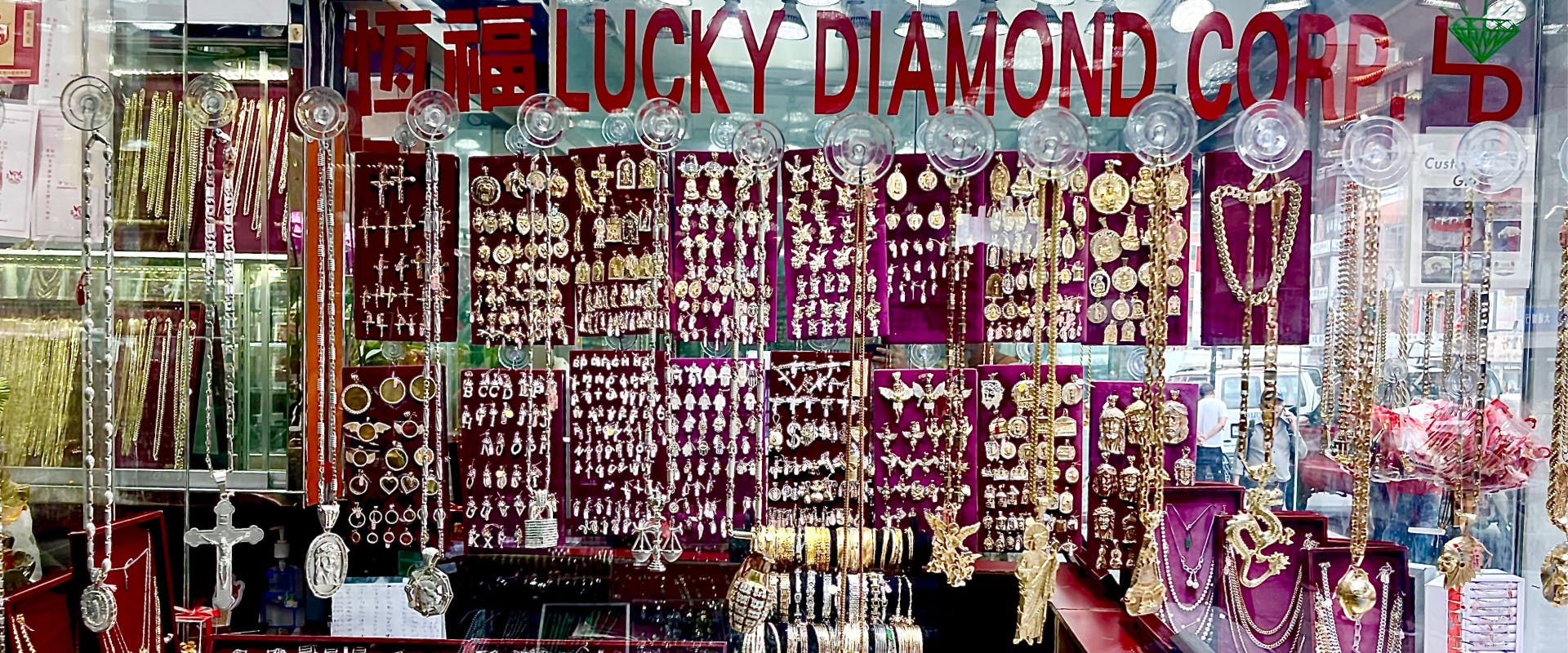

As his prominence rose, so too his ability to adorn his body in progressively large and numerous chains and jewels. He saw himself as a "jewelry extremist" building on the opulent traditions of Sammy Davis Jr. and Mr. T. Walters, as a teenager, would take the five or the six train from the Bronx to Canal Street in Chinatown and weave in and out of window foyers marveling at the enormity and glow of the gold and diamonds in the windows.

He'd slink through Chinatown dreaming of when he would get on and the various accoutrement he'd adorn his own frame in, wrist, neck, hands and eyepatch. The proximity of New York neighborhoods allowed immigrant and working class communities to window shop their dreams. Aspirations from 5th Ave to Orchard Street that produced a million bootlegs and sent scores of teens to bum rush department stores. Hip-Hop has always had a long relationship to luxury.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

Hip-Hop Thousandaires

In the day, Asian, Jewish, and Italian-owned stores began to cater to an emergent class of young Hip-Hop thousandaires. Some businesses turned away the young patrons of color, not wanting to associate their store with the culture or race or class of these would be buyers. But some businesses embraced the culture and saw Walters and his generation as early influencers when social media was what you could see on the street and then on the cover or back jacket of an album. Vietnamese jeweler Johnny Dang, Uzbek Jacob Arabo better known as Jacob the Jeweler and stores like Popular Jewelry and Mongolia and Golden Jade Jewelers were early and consistent sources for coming up on regalia for 80s and 90s stars.

These larger than life jewels became a motif of Hip-Hop style that some people lauded, and others hated on, making arguments against rabid consumerism and the symbolism of seeing Black folks in chains. But for many, Walters included, the adornment meant something different altogether. He wrote for The Guardian in September 2022 that, "I feel it in my DNA. My jewels are my superhero suit, an extension of my beautiful brown skin. It’s a gift from ancestors who sat on thrones and reigned with rings and rocks the size of ice cubes."

"You gotta be large" Walters said in an interview for GQ magazine's YouTube channel in November 2018. And I mean, who ruled larger in our imagination than Slick Rick. There's the towering libra scale on the cover of The Ruler's Back, his sophomore effort on Def Jam in 1991. Walters is a Capricorn but the libra scales were the biggest pendant in the window the day he went scouting for a memorable piece. On his 1999 Art of Storytelling, Walters is writing with a quill and his right wrist is dripping in diamonds and platinum. A square diamond pinky ring big enough to serve a meal on. A Rolex from Jacob he acquired in the 80's, looks like an iced-out saucer used in formal tea service.

Living Large as a Symbol of Empowerment

Living large is a way to say prominent, to announce you've made in an industry that sought to deny your genius. A way to say you've made it in a country that has consistently challenged your ability to do so. Living large is a kind of metaphysical ars poetica, ushered in by artists like Walters, to make Black life undeniably visible in a system that has sought to deny and dehumanize them. The adornment of the body is a way to resist, to pronounce loudly that one is indeed here and present and unmissable. Like graffiti and the boombox, the audacity of the jewels, of living large, is to be unmistakably present, to be shaken awake in the streets, on the train, from the comfort of your suburban home and be made to wrestle with the flyness, the 'what the fuck is that'-ness, the aesthetic ingenuity of a generation that was tired of waiting and turning the other cheek.

Living large is the flex. The fetish for the fresh. The look over here. The can't miss me. The drip. The swag. The you-ain't-never-seen-it yet you gotta have it. Living large is the encouragement to continue. To follow a dream. To live without apology, without a care. To adorn one's body and home and car and teeth and feet, in what feels fresh and cool to you. A kind of signature and fingerprint, when done right. The height of individuality. To own one's image, in a contested landscape and history. To elevate oneself. I self, lord and master. To ascend to the throne of your own life. Dipped in gold or not. Walters gave a generation permission to aspire to the flyest of heights and dream that we controlled our own world and destiny and that we were the authors of our own story and could be as vibrant and as fly and as large as we wanted to be.