PHADE: Portrait of a Shirt King

PHADE: Portrait of a Shirt King

Published Sat, June 6, 2020 at 5:00 PM EDT

What do Mike Tyson, Run-D.M.C., Flavor Flav, LL COOL J, Big Daddy Kane, JAY-Z, RZA, Biz Markie, Bell Biv DeVoe, and Queen Latifah have in common? They’ve all rocked clothing touched by the Shirt Kings.

Today marks the anniversary of when the Shirt Kings first opened at the Jamaica Colosseum Mall on 6/6/86.

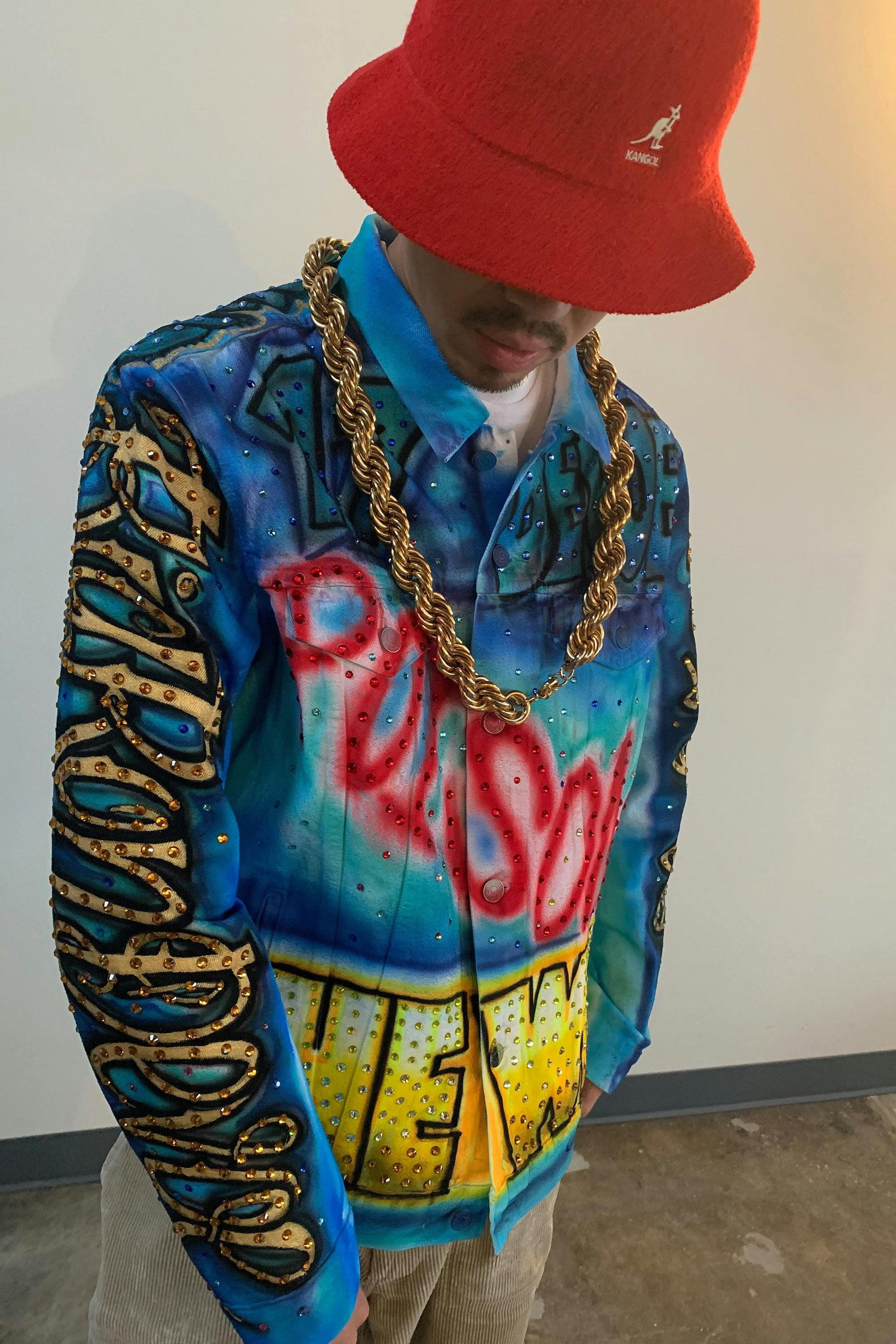

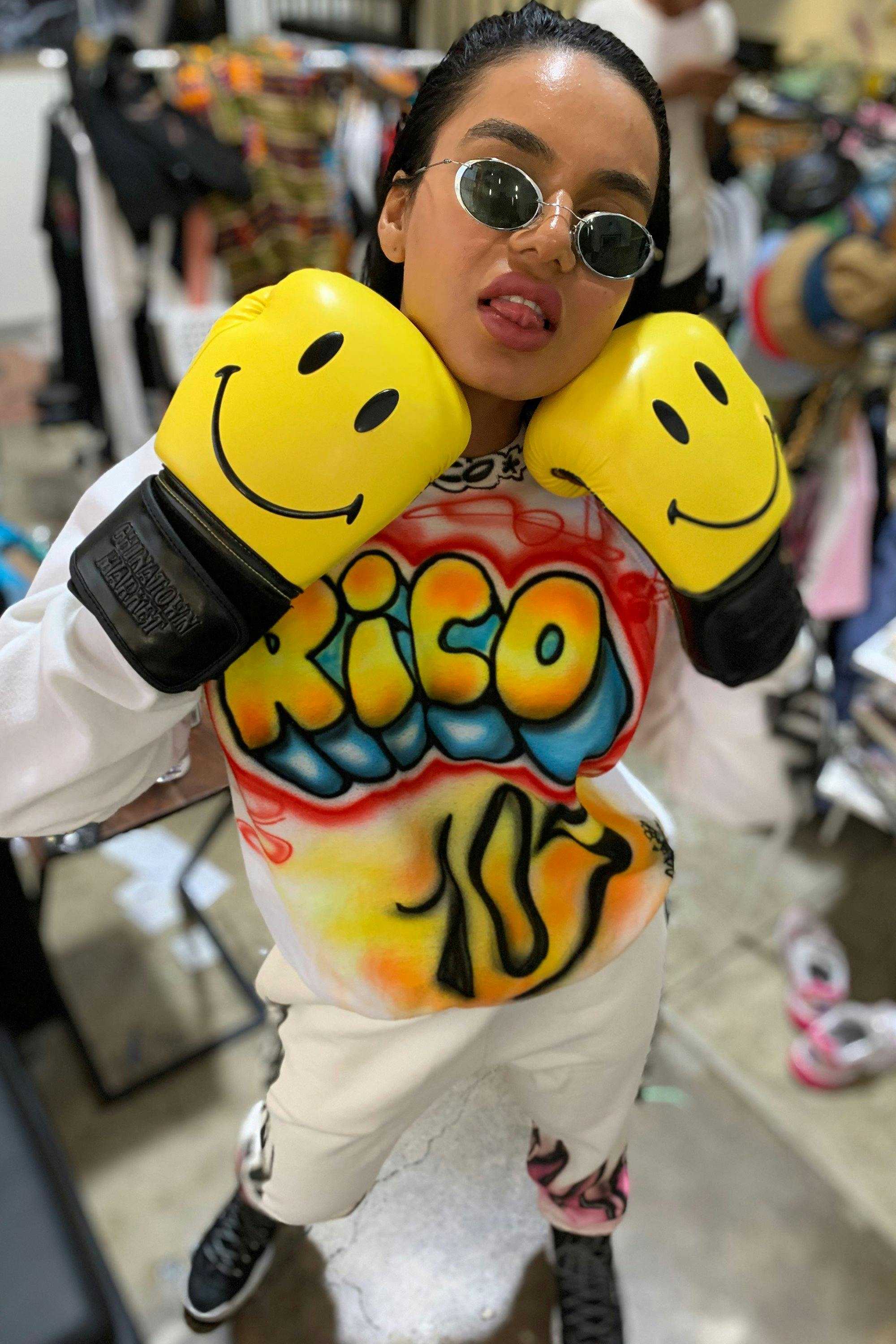

Style has always been a key component of Hip-Hop, and while every ’80s and ’90s kid in the U.S. probably had an airbrushed T-shirt blaring their name and a bad caricature from the local boardwalk or county fair, New York City kids were getting fresh custom designs splashed across shorts, jackets, pants, and sneakers — and if you were really down, you went to the Mighty Shirt Kings in Queens, at the Jamaica Colosseum Mall.

The Shirt Kings empire was built on the foundation of friendship between Edwin “Phade” Sacasa, Rafael “Kasheme” Avery, and Clyde “Nike” Harewood — three friends from Manhattan’s High School of Art and Design whose hard work, artistic gifts, and big dreams led them to become the clothiers of rap royalty.

PHADE documented it all in Shirt Kings: Pioneers of Hip Hop Fashion, a book of his own photographs as much an exhibit of his artistic journey — a slice of old New York so vivid you can almost smell the acrylics coming off the page.

So how did this graffiti kid born in Brooklyn and raised in the Bronx come to work with the biggest names in Hip-Hop and Hollywood, his artwork still gracing streetwear made by Supreme, Stüssy, Nike, and Champion, among others? Here, Shirt King Phade bequeaths us a story in his own words.

Photos: Phade / Shirt Kings

ZERO POINT

When my family moved from Brooklyn to the Bronx, we were exposed to the whole beginning of Hip-Hop. I was watching my brother, FLY-1, do graffiti when I was 8. Every Saturday morning there would be like 12 to 15 guys and girls and they would just go somewhere, come back. They’ll have a bunch of paint and then they’ll go somewhere again, which I found out was the train yard, which was super close by. Then they would come back running with paint all over their clothes. I was like, “What is this all about?” I was excited. I found out they were writers. They would have their little pow-wows, talking about RIFF 170 and how he was one of the style generals. But the top dog they would talk about was PHASE 2. He was the pinnacle. There were others, too, like BILLY 167, TRACY 168. But PHASE was I think one of the first guys to actually do style with arrows, and everybody followed suit. You would never see him. He was this mystery. If you knew him, you were blessed. If someone said “I met PHASE,” you were like, “No, you didn’t.” This was 1976.

I started bombing “PHASE 3” and people were like, hmmm … okay. I was the big-time toy. But I was getting out around the way and learning the ropes and meeting people.

A DJ named Jerry moved into our building. He came from Patterson Projects, where the Casanovas were, where Grandmaster Flash was. So he came uptown and his friends would hang out and I was like, my God, these guys are breakdancing, doing all kinds of weird stuff that I’ve only heard about.

I begged him to teach me how to paint on people’s pants. He said, “You need to get acrylic paint,” and I go, “Okay, cool.” I went and got some acrylic paint. I was like, “Why is it not coming out like yours?” He was like this Mr. Miyagi-type of teacher that would give you bits and pieces without the whole formula. He and his partner, DJ Doc La Rock, were showing me the secrets of using primer when I was 12.

They said, “You need to go to the High School of Art and Design.” I heard it from the school counselor, from peers, friends, whatever. But these two were giants in my world. I found out there was an entrance test and there were a whole lot of other loops I would have to go through. My mother pushed me because the requirements were to have some kind of portfolio, and she bought me a portfolio and helped me put my Mickey Mouse drawings and all kinds of stuff together.

That school opened up worlds to me. It was a melting pot. When I got there, there were writers from all over the city. Places I’ve never heard of. Places I’ve never been to. The third-floor and fifth-floor bathrooms were covered. It was like a New York City subway train. All the things I saw on the train were in the bathrooms. So I was reading names, thinking, “Hold up, this guy goes here? This guy goes here? This guy goes here?” It was a who’s who gallery, basically.

People really started giving me flak for my name, so I got in my think tank — my bed at the time — and thought about what name I wanted to write. I thought maybe I could fool them with a PHASE 4 or something? Nah. I liked the “PH” so I went down the alphabet. PHABE would only make sense if I was named Fabian. A guy in the building down the hall from me already wrote F-A-C-E … and then I went down to D and it clicked: PHADE.

I did a ghetto Google check and asked all the elders.

I asked Jerry. I asked my brother. “Has anybody ever wrote PHADE?” And they all said nobody had touched it. And then I said, you know what, let me add the number 2 because I want to be as close to PHASE 2 as possible.

Photo: Phade / Shirt Kings

DAGGER STROKES

When I got to Art and Design, I joined the MTA crew because there was an amazing artist there named Chino Malo. He was this precursor to a lot of other guys who would do characters like his, with the big sneakers and the big bell-bottomed pants and ski goggles. He was a master.

I had a partner named PACER 1, and me and PACER were bombing in this unspoken competition between us until we ran into these two other guys, CUE ONE and MON2/LC, in the 241st Street yard. We became good friends and I joined their crew, TNT. Our rivals were TMT. We kind of secretly looked up to these guys. But we never let them know. We had a race with TMT for the insides, like who will be the king of the insides of trains, and that went on for like a month. I believe we bombed them out and TNT became kings of the insides of the 2 and the 5 trains. We had a lot of firepower, some great kids from Art and Design that were tagging with me.

When I got to Art and Design, I was so intimidated by the other artists. I went into the photography department, so I had a 35-millimeter went with me everywhere I went. I caught a lot of lifestyle photos. Sometimes Henry Chalfant would be close to the platform while I’m on the other platform taking photos, documenting my crew and anything that was hot coming by.

DAZE and ATOM put me and Chino Malo onto that whole MTA life.

When I took over TNT I put SEEN onto it, LADY PINK, DOZE, MARE, the whole team. I was their elder, so TNT was ruling because they were younger and hungrier than me. COMET gave TC5 to L’IL SEEN. And that team morphed into TC5 — The Crazy 5. The younger ones went bananas with it. They changed it to The Cool 5. And The Cool Five was also RSC, Rock Steady Crew. DOZE was in high school with me.

Art and Design was so pivotal, because not only did I meet my friend, Clyde, who is Nike from Shirt Kings, and Rafael, who is King Kasheme from Shirt Kings, but I met Darold Ferguson: D-Ferg ... he had a brand called Ferg 54. He was A$AP Ferg’s dad.

The original Shirt Kings was just me and Darold at first. After high school I would run into him in Harlem. I learned how to airbrush in ’84 through a TC5 member, SOUND 7, while home on Christmas break. He had actually put the airbrush in my hand because I put a spray can in his hand.

When I saw the airbrush, I was like, “What the hell is that? What are you doing, man? Are you sniffing this or smoking this? What the hell are you doing? Are you creating paint LSD or some shit?”

I just didn’t get it. He was like, “Use the force, Luke. Use the force.” And I was like, “This dude is a space cadet for real.” And I locked in and drew my first shirt. It was an Ernie and Bert. He set me up with a compressor. He gave me an airbrush. He kept pushing me into destiny. Him, SPANKY, TC5, PINK, they were all already airbrushing.

I went back to school [at Savannah College of Art and Design] and became the man. Nobody was painting with an airbrush in Savannah. I would work all the fairs, but I was doing graffiti. I started doing T-shirts there. I came back home in ’84 for the summer and was teaching classes to kids, working as a camp counselor. I ran into Darold, and he was like, “Yo, I’m doing shirts too.” I had two of the young guys from the projects helping me sell T-shirts on the corner of 125th Street. Darold had a team who were painting acrylics. He was drawing those characters from that “How to Draw” animation book that everybody used to have. Then he started doing Benz symbols and BMW symbols, hand-painting them. And they were coming out amazing. I was doing mostly graffiti letters. Once in a while my own characters, but a lot of bubble-style letters. Darold was the one that said, “You need original characters,” and he was like, “What’s up with your boy Kasheme and Nike? Them dudes do characters.”

Darold also put me on to the Eisner Brothers down on Delancey and Essex Street. They supplied him with the Russell jerseys, the best shirt at the time. Champion didn’t have sweatshirts of this caliber. These shirts had like a soft-cotton Euro feel to them.

I found myself at Kasheme’s house in Jamaica, Queens, a lot. In the years that I hadn’t seen Kasheme and Nike, they both had gone into the construction business. Nike was doing masonry and Kasheme was doing flooring.

I showed Kasheme what I was doing with shirts and he got excited. He said, “I just got laid off, and with my last check I’m going to buy an airbrush.” Everywhere I went I was making money. He would be like, “Wow, it’s that easy?” I kept 10 shirts in a bag and sold them for $20 each.

ATOMIZED

Kasheme’s friend from work, Hal, was from Hollis, Queens, and was Run’s best friend. Hal set it up. We walked all the way to Hollis, Queens, and Hal was like, “I’m going to take y’all to Jay’s house.” This was early ’85. Run-D.M.C. was ruling the world at the time.

When we got to the house, Hal knocked on the door and Jay came out. And he was like, “Yo, Kasheme, what’s up?”

And I was like, “Oh, my goodness. He really knows Jam Master Jay.”

I couldn’t believe it. After introductions I went in my bag and pulled out a shirt. And Jay was like, “Oh, that’s pretty cool.”

But I had known I was going to his house, so I had made a black shirt with a gold chain on it, thinking that the black and gold would get him. I pulled out this other shirt and he was like, “Wait, wait, wait — you got something there.” That one I airbrushed and then painted the acrylic on top of the design, so it had the feel of a nice rope chain.

He said, “I need two of them shirts … one for me and one for Little Jay.” I was like, “All right, cool.” And I charged him $100, and at the time I was only charging like 15 to 20 bucks. But I had done my first gallery show with PINK and a lot of people from the Lower East Side at the Rainbow Connection Gallery on Varick Street. I saw the power of the art there. Though I didn’t sell at the show, I was exposed to selling. I maintained my high prices because PHASE, DELTA and SHARP, they went with the first wave of Hip-Hoppers — I think like in ’81, ’82 — to Paris. And when I ran into DELTA he had all this money in his pocket, and he was like, “Yo, I sold a canvas for $20,000.” I knew the potential. One of my first shirts I did was for Larry Love, a dancer for Grandmaster Flash. He wore one of my shirts on stage and all I could see was that shirt. In ’83 I had also seen DOZE paint the hallway of the Roxy, and I was like, “Man, it’s happening. This is really going down.”

I’m not from Queens, but Queens was where God decided for me to plant and for this thing to begin to grow.

And Jay put the validity stamp on it. This was a huge moment for me. Run-D.M.C. were making clean money. My exposure uptown in Harlem and Bronx showed me everybody hustling. Shirt Kings was a natural evolution of my whole lifestyle. Jay said, “This is what y’all do. Go to the Ave, find a spot, and I’ll put up the money.” We walked away like “wow.” A couple of days later we signed a lease on a double booth at the Colosseum. I paid for it myself because I was making money with the T-shirts. This is hustler’s rule number one: “Take no money from nobody.” They only had a few other vendors in there at the time and they looked at us like outlaws. They put us in the back. We had this big boom box. Kasheme taped Marley Marl and DJ Red Alert every weekend. We called it Shirt Kings because Kasheme had joined the Five Percenter Nation, so he considered himself a king. We thought it sounded dope.

ETERNAL MIX

The second week that we were open, Jam Master Jay came to see us after he had been on tour for two weeks. Hollis came rolling in — the 40-ounce guys, they were the Vikings of Queens, burly guys coming down the Ave, nobody’s gonna mess with them. They came down the stairs of the Colosseum and it was like you heard the song, “Hollis, Hollis, boom-boom-boom.”

Black jackets, adidas, godfather hats, Gazelles, and Jay’s in the front wearing big gold chains.

He comes down to us and is like, “Yo, y’all did it! You did it!” He saw the vision and he gave the word and then he saw that word manifest. That made everybody in the whole Hollis crew start ordering shirts.

He was keeping it a secret for a while. People were asking him about the shirts. I knew because people would finally come to Shirt King and were like, “Hey man, I seen Jay’s shirt!”

I guess LL saw his shirt at the office or on tour.

When he came down, we could see him searching … he went to the sneaker booth, I think he went to the silver booth, the fur booth, he went to the gold booth, he went to another booth and he went to the big tent, and in my animated way, I saw him, his hat bobbin’ around going from booth to booth like a shark’s fin. He was navigating through. He finally made his way to us and we played it super cool and just kept painting. He just stood there for a long time just staring at the shirts, and I was like, “Oh my goodness, please say something. Do a rap or something.” I’ve never heard his voice so I’m thinking he’s going to yell at us. Mind you, I had heard “Dangerous” and had been watching the DJs in my project spin his music. L wanted a caricature of himself. Nike had the stronger skills in that department, so it was like okay, we want you to do it. Then Kasheme just pretty much did the design and said, “Okay, the caricature is going to be here. The car is going to be here. What kind of car do you drive? We hear that you’ve got this, you’ve got that.” LL said, “I’ve got the Audi.”

He placed an order. He spent a lot of time making a decision and we’re still seeing the effects of the fruit of him spending that time there. L was such a visionary. I wouldn’t have even guessed the things that he was going to do. He adopted us. He wore his shirt on every magazine cover you could think of.

It wasn’t like, “I’m going to do this for you guys.” It was just a Queens thing. It’s kinetic. We didn’t ask him to do it.

When people saw the LLs coming through and the Jam Master Jays, that gave authenticity to what we were doing, you know. The Salt-N-Pepas came down, the Prince Markie Dees and the Fat Boys. The Colosseum caught the vision finally and they allowed us to expand. We expanded up to Harlem, working out of a back room at Dapper Dan’s. We expanded to Miami through Luke Skywalker in ’88, Long Island, Brooklyn, Baltimore, Northrup, Atlanta, and Darold introduced me to Puffy in DC.

It’s crazy. We were fought at first — the music, the radio, people hanging out. The Colosseum tried to shut us down but they had to respect us because we were not connected to any destructive element. Finally we were like, “Nobody’s shutting us down. We’re bigger than life.”

I think LL really said it the best when he said it was the first time that he saw Hip-Hop embodied in one place. Everything was there — all the elements collided together at Shirt Kings.

* Banner Image: LL COOL J WEARING SHIRT KINGS / PHOTO BY PAUL NATKIN/GETTY IMAGES