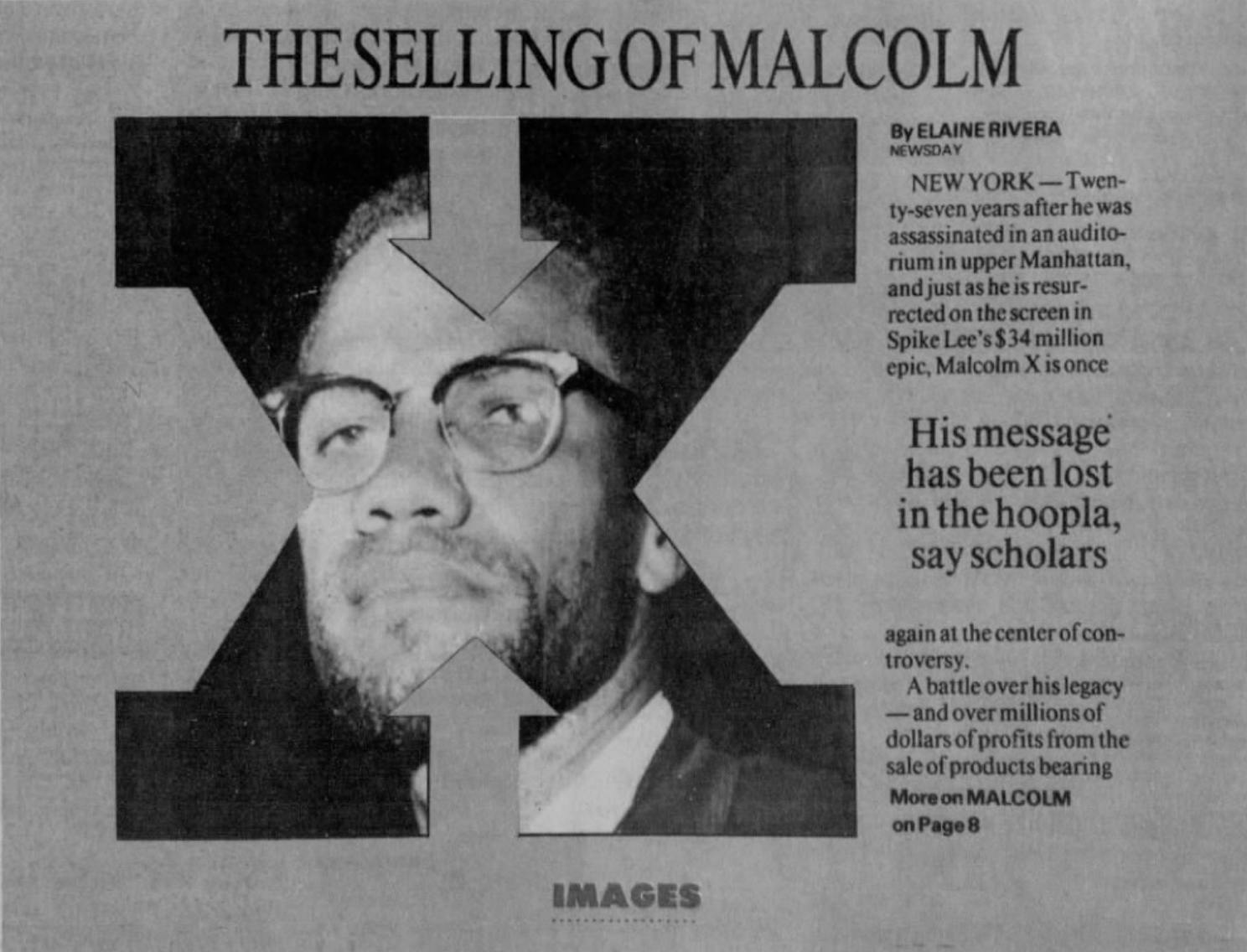

The Merchandising of Malcolm X

Who Got Rich Off All Of Those Malcolm X T-Shirts?

By Alec Banks

Published Sat, November 19, 2022 at 11:00 AM EST

Malcolm X and Alex Haley split a $20,000 advance from publisher, Doubleday, to produce what would become ‘The Autobiography of Malcolm X.‘

During the writing process, the freelance writer and civil rights activist would stay up through the night in an 8x10 foot apartment in Greenwich Village. Anyone eavesdropping by the door would have heard the sound of Haley’s typewriter, Malcom’s voice, and smelled pot after pot of coffee being brewed.

"MY whole life has been a chronology of changes," Malcolm X stated.

They did more than 50 interviews before Malcolm X’s assassination at the Audubon Ballroom in Washington Heights. In the aftermath, Doubleday cancelled their contract with Haley — citing the safety of their own staff. Barney Rosset of Grove Press — a proponent of voices ranging from Che Guevara to Ho Chi Minh — picked up the contract.

Between 1965 and 1977, The Autobiography of Malcolm X sold six million copies worldwide. The manuscripts for the book remained in the possession of Alex Haley, and when he died, they went to auction to settle claims against his estate. They were sold for more than $100,000 to Gregory Reed, a Detroit-area lawyer.

The book rights, pieces of unpublished chapters, and a slew of other literary assets are but a small piece of the currency attached to the Malcolm X estate. But for Hip-Hop fans of a certain age, one might be left asking, “Who made money off those ‘X’ T-shirts?”’

The fashion statement — with X's emblazoned on T-shirts, hats, and sweatshirts — intermingling with Pan-African colors, became a cultural insignia, not unlike other popular fashion marks like Nike's Jumpman and adidas' Trefoil logo.

The popularity of the X branding can be directly tied to Spike Lee's 1992 film, Malcom X, starring Denzel Washington in the titular role. Lee, who played a major role in branding Michale Jordan's shoes using his Mars Blackmon character from She's Gotta Have It, opted to promote the film through fashion.

In 1990, Lee opened up his gift shop, Spike's Joint, in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn, where he talked about the importance of Black ownership.

"We gotta start working for ourselves instead of working for other people." - Spike Lee.

In 1992, Malcolm X's widow, Dr. Betty Shabazz, turned to Mark Roesler, the chief executive of the Curtis Management Group of Indianapolis, to help determine what, and what was not, protected under the law when it came to Malcolm X merchandise. At the time, the group also controlled the estate rights for other notable figures like Humphrey Bogart, James Dean, Babe Ruth, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Mark Twain. Today, they control varied rights — including William "Buckwheat" Thomas — who remains a stereotypical caricature of Black children.

For some, the letter “X” was simply part of the alphabet, and for others, it was synonymous with the man himself. But with the popularity of Lee's film, the interest — and perhaps more importantly the money — made Malcolm X's estate that much more valuable. At the time, industry licensing veterans predicted that $100 million of merchandise could be produced in 1992 alone. At normal industry royalty rates, the estate could potentially net some $3 million.

When Lee produced his merchandise, he did it without the blessing of Curtis Management Group. The irony is that Malcolm X, like many members of the Nation of Islam, assumed the letter — now held to represent his identity — as an expression of a lack of identity. But by the end of his life, Malcolm X had also left "Malcolm X" behind, along with Malcolm Little and his street name, Detroit Red. In 1964, after a trip to Mecca, he became El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

When he was still alive, he grew increasingly concerned about the way he was depicted to the public. He named Robert Haggins as his personal photographer because he felt that the wire services often editorialized him in ways to make him appear dangerous.

With Malcolm X merchandise selling in huge volumes, Conrad Muhammad, a spokesperson for The Final Call, the Nation of Islam’s newspaper, wrote, "In 1992, Blacks again are witnessing the murder of Malcolm X, but this time it is the man's legacy the enemy is destroying; and they are doing it with the approval of black consumers."

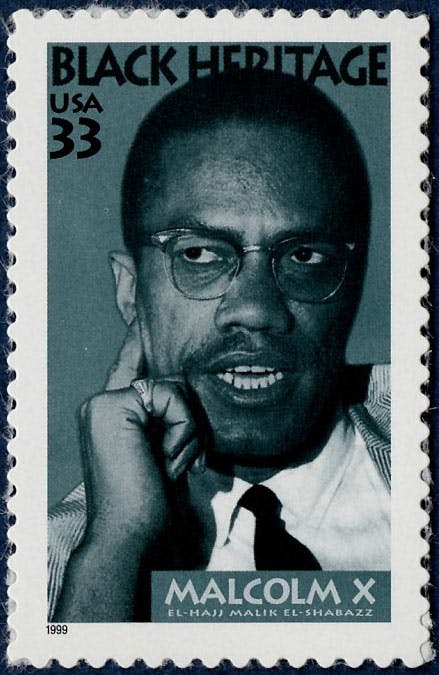

The "X" phenomenon went beyond Malcolm. Madonna thought of calling her book "X" before settling on "Sex." Cross Colours combined the letter with a cross and a circle representing the merging colors of South Central Los Angeles's uneasy gang truce. And in January 1999, the U.S. Postal Service issued the Malcolm X stamp.

In 2014, Nicki Minaj used a Don Hogan Charles photograph of Malcolm X holding a M1 Carbine — which appeared in both Life and Ebony in 1964 — for her single "Lookin Ass N---a."

The family of the slain leader did not take kindly to the controversyy. Mark Roesler called the image "dehumanizing." He added: "This is a family photo that was taken out of context in a totally inaccurate and tasteless way."

As of 2009, the marketing of "dead celebrities" was an $800 million dollar a year industry.

It's interesting to examine the "X" trademark along side the usage of the phrase "Black Lives Matter." Since 2015, there have been 15 trademark applications seeking the registration of “Black Lives Matter” for various goods and services. However, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rejected every application.

In order to function as a trademark, a slogan needs to convey the source of the goods and/or services to the public. It is a ubiquitous slogan to “raise awareness of civil rights, protest violence, and convey the message of support for the same.” Ultimately, the USPTO determined that “Black Lives Matter” belongs to the movement, not to an individual person or entity.

When the "X" phenomenon was at its height in 1992, Curtis Management Group received 90 percent of the wholesale price of an individual unit. At the time, about 40 apparel companies made between 160-170 different products. One merchant, who regularly sold leather jackets with an X on the back remarked at the time. "It's gotten to the point where there's so much out there that the kids who want the jacket, have it."