How Answer Records Laid the Foundation for Future Battle Rap Culture

How Answer Records Laid the Foundation for Future Battle Rap Culture

By Alec Banks

Published Wed, May 13, 2020 at 3:35 PM EDT

Battling remains a core tenet of Hip-Hop. While this form of one-upmanship may seem like it’s unique to the culture, history tells us that this verbal assault was a remix of past traditions.

Answer records have their roots in the early 20th century. Unlike what we’ve seen in a Hip-Hop context, these songs weren’t laced with insults. Instead, they were serialized like a TV show — allowing listeners to follow along as the plotlines evolved, and as the point of view shifted between artists.

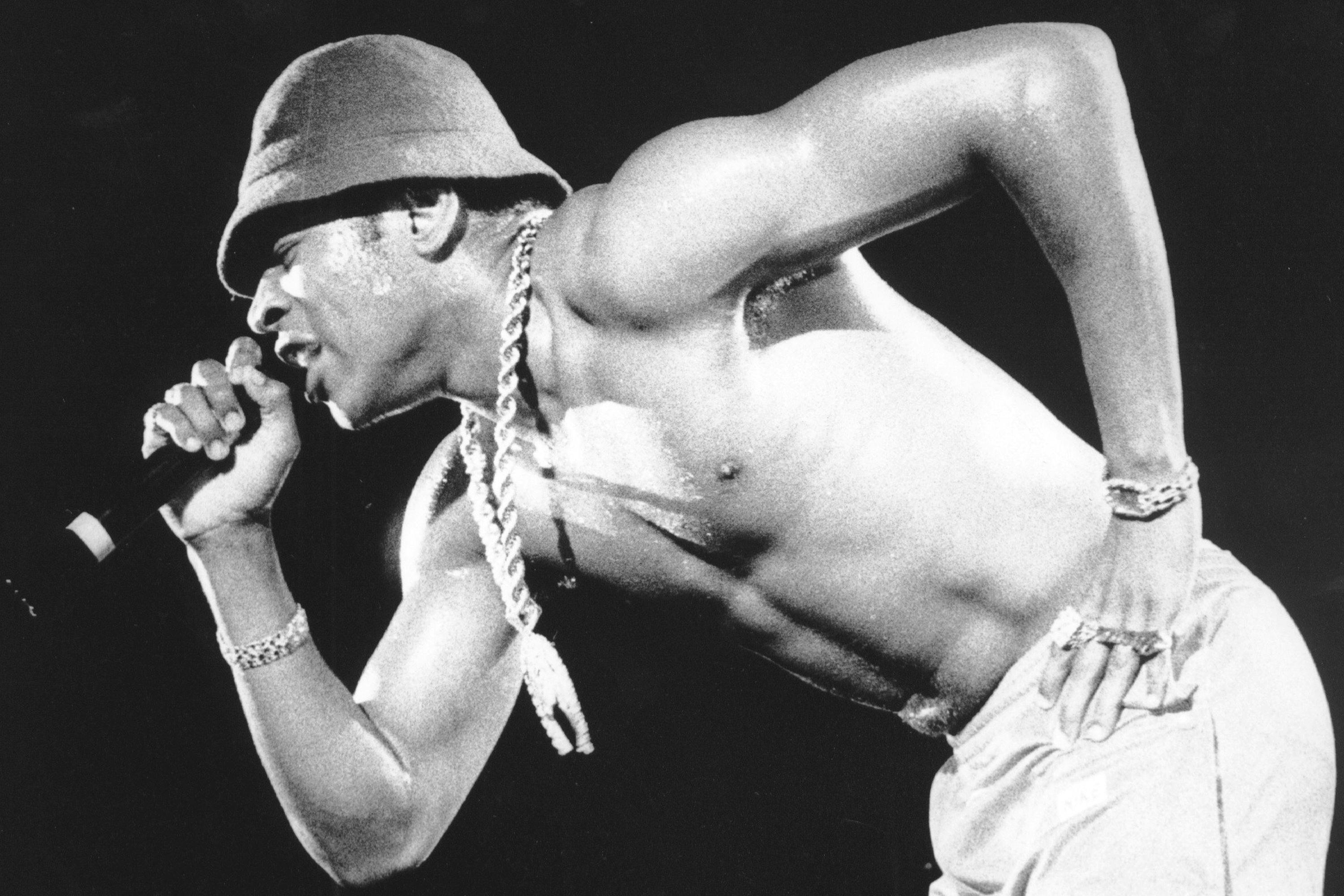

Photo by David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

For example, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters recorded “Work With Me, Annie,” which spawned Etta James’ “Roll With Me, Henry” and, later, Ballard’s final comment, “Annie Had a Baby.” We also got notable back-and-forth between artists like Ben E. King and Damita Jo, Muddy Waters and Bo Diddley, the Miracles and the Silhouettes, and Michael Jackson and Lydia Murdock.

This format not only laid the foundation for the competitive nature of Hip-Hop itself but also the legendary beefs on wax from the likes of Kool Moe Dee, Busy Bee, MC Lyte, Antoinette, LL COOL J, Ice Cube, Roxanne Shanté, and more.

Shanté recalls the answer-record phenomenon of her childhood, when men proclaimed themselves “kings” — and female artists answered right back by stating that they were “queens.” Having grown up with her mother and three younger sisters in the Queensbridge projects in Long Island City, this sense of female empowerment on a record — especially in response to a male figure — really resonated with her.

“It never dawned on me that later on in life I would actually do that,” Shanté admits.

Shanté had what she refers to as “Nipsey Russell Syndrome,” recalling the ’70s entertainer who showcased his ability to answer questions in rhyme form on programs like The Flip Wilson Show and Hollywood Squares. She didn’t necessarily know at the time how — or why — God selected her to have such a unique talent, but it didn’t take long for her to weaponize it.

Others might have turned this skill into something of a parlor trick performed on the playground blacktop, but Shanté channeled her skill into something different: battling.

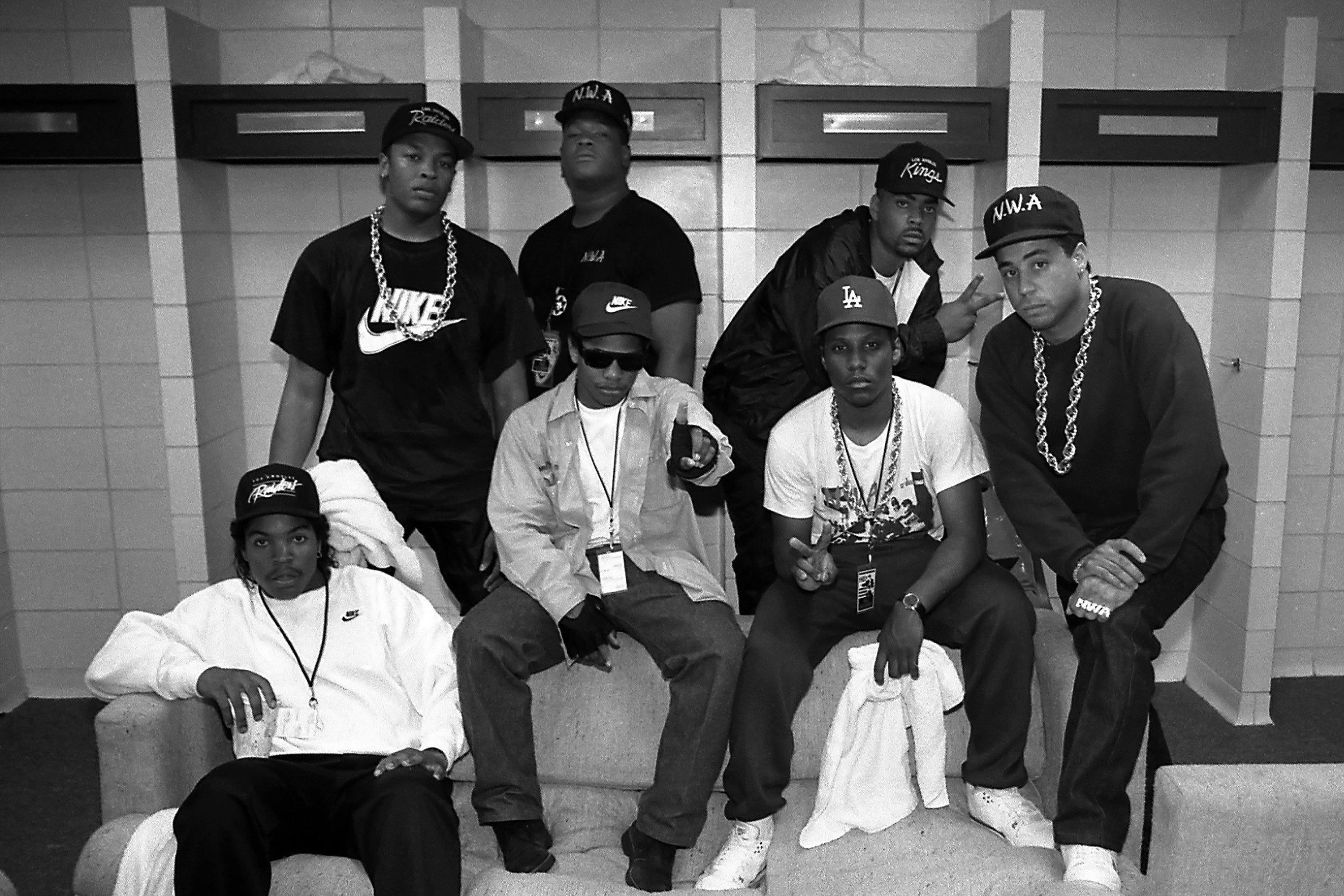

Photo By Raymond Boyd/Getty Images

As a child of the ’70s, her personality was shaped by Hip-Hop culture. By 1979 — six years after Kool Herc’s rec room party in the Bronx — a 10-year-old Shanté was battling men twice her own age. She would stand on top of a milk crate and deliver the first blow, which was usually fatal.

“It was like landing that perfect punch in a boxing match,” Shanté admits.

“And the quicker that you’re able to do it, the better. If you were able to get in there, grab the mic, spit your lyrics, control the crowd, and the other person has no comeback, that was like a first-round knockout.”

If her rival had the skill to make it several rounds, she would always have responses to everything that they said. For Shanté, she was simply carrying on the tradition of the answer records — albeit in real time — and especially relished the feeling of breaking her opponent down like Muhammad Ali.

“Ali once said, ‘There are as many people here to see you win as there are to see you lose,’” she explains.

Photo by Raymond Boyd/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Shanté had no problem embracing the role of villain. Not only was she winning; she was also turning battling into something of a family business. Her mother — along with a neighborhood entrepreneur named Petey Green — would put up money for high-stakes competitions.

“I remember my mom going and getting her ‘standup cash’ — that’s what we called it. And she’d be like, ‘Now don’t lose this shit because I don’t want to owe nobody this money,’” Shanté says.

Soon after, $50 park rumbles turned into a $1,500-a-pop business venture built upon telling someone that their breath stunk like old bus seats. Simply put, if Nipsey Russell was a syndrome, Roxanne Shanté was now the plague.

Answer records may have pre-dated Hip-Hop music, but Roxanne Shanté perfected the format. Unbeknownst to her at the time, her growing reputation in Queensbridge was going to open doors for her.

It was now time for an all-out war.

* Banner Image: Roxanne Shante / Photo By Raymond Boyd/Getty Images