The $84 Million Dollar Drug Empire And The Man Who Bought The Apollo Theater

The $84 Million Dollar Drug Empire And The Man Who Bought The Apollo Theater

By Alec Banks

Published Thu, May 5, 2022 at 4:39 PM EDT

"Thinking bout Guy Fisher/Never met him, but God damn, that's my n*gga!/I figure real estate invested pie flipper/Never snitch, me, I'm in a bathrobe, fly slippers." - Cam'ron "Get It In Ohio"

In 1972, Leroy "Nicky" Barnes formed "The Council" to manage and supervise the distribution of drugs in Manhattan, the Bronx, and Brooklyn. The Council was based on a "democratic format" — with one vote per man — with each of the members a subsidiary company. Whereas La Cosa Nostra was formed upon a tenet of Catholicism, Barnes built The Commission using aspects of Black Nationalism, and Niccolo Macchiavelli's The Prince.

''We decided that we would pool our money together in an effort to purchase narcotics at a cheaper price,'' Barnes said.

Two of his alleged top lieutenants were Guy Fisher and Frank James. Barnes was almost 40 years old. Fisher was 23. According to an undercover DEA agent, Louis Diaz, The Council was taking in as much as $84 million a year.

Guy Fisher is a lesser-known piece of the puzzle when examining the heroin trade in New York City in the mid '70s. For some, "moving weight" meant transporting record crates to park jams during Hip-Hop's infancy. For Fisher, he used Barnes' tutelage and created A DJ Kool Herc-esque "Merry Go Round" between the plug, dealer, and user.

Fisher was born in July 1947. He and his five siblings grew up in the Lester W. Patterson Houses — one of the first public housing projects — in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx. At the time, it was a melting pot of different ethnic and religious backgrounds like Blacks, Puerto Ricans, and Jews. The Patterson Houses, and the rest of the South Bronx, began to change in the 1960s when drugs and crime flooded the streets and middle-class families fled.

To those who knew Fisher best as a young man, he was in and out of trouble. But, when he was free from the shackles of reform school, Fisher had a knack for selling things. First, it was shopping bags. Then, it was used clothing he bought on Delancey Street which he marked up and sold. Acquisition and product mark up were things Fisher inherently understood.

Nothing suggested that Nicky Barnes' empire was crumbling. In fact, his "Mister Untouchable" moniker seemed more like a fact, than braggadocio. He had a record of 13 arrests dating back to 1950, when he was 18. But the system rarely — if ever — got justice.

On May 8, 1975, Barnes was acquitted of a bribery charge involving a police officer. In March of 1976, he was acquitted of a murder charge by a Bronx jury. On October 26, he was arrested in the Bronx for possession of a gun, but the charge was dismissed. During that five‐year period, Nicky Barnes was charged with homicide, bribery, drug dealing, and possession of dangerous weapons. However, the only time he had spent in jail was 150 days on various charges while bail was being secured.

When The New York Times Magazine wrote the now ubiquitous "Mister Untouchable" cover story in 1977, they used a specific anecdote to illustrate just how brazen and above-the-law Barnes thought he was.

During an adjournment on charges for possession of hash, several guns, and nearly $45,000 in small bills, he entered the washroom inside the Criminal Court where he saw two narcotics detectives that he knew. After washing his hands, he said to himself in the mirror, “I need a handkerchief. Let's see, is this a handkerchief?” He reached into a side pocket and pulled out roll of bills.

“Oh,” he said. “That's not a handkerchief, is it?”

The wad went back in Barnes' pocket. He reached into the other side pocket.

“Is this a handkerchief here?” and pulled out a duplicate roll. “Now, that isn't a handkerchief either, is it?”

He shook his hands dry and walked out of the washroom.

At one time, Nicky Barnes' police file went by the name of “Operation Slick.”

The law finally caught up with Nicky Barnes in 1978. He was sentenced to life without parole for his role in the massive and far-reaching drug conspiracy. Despite Barnes' departure, officials in the Police Department's Narcotics Bureau said that Harlem was still the center of heroin trafficking in New York area.

Fisher and James became his logical successor. Sterling Johnson, the city's Special Narcotics Prosecutor, confirmed as much, stating that they “are the likely contenders to replace Barnes.”

With the added attention from both the police and the press, a more thorough composite of James and Fisher began to emerge — albeit a loose one.

Beginning in 1958, James had been arrested six times on narcotics and other charges and served a prison sentence for manslaughter. Fisher, then, 32, had been arrested 11 times, including on accusations of narcotics conspiracy, assault, and possession of a gun.

In 1974, Fisher was pulled over in lower Manhattan. After a thorough inspection, police found $103,740 in a shopping bag in the trunk. Like Barnes, Fisher was later acquitted of charges that he had attempted to bribe the arresting officers.

Fisher utilized lessons he learned from Barnes. For example, the operating cost of flooding the streets with heroin. It took 16 hours to cut 15 kilos of heroin. Instantly, the $150,000 investment was worth $630,000. The operating cost was 170,000, including the cash fees to the women and their apartment guardians. Fisher stood to make $460,000 in profits for every $150,000 he spent.

And then there were lessons he didn't want to take with him — like Barnes' opulence — which included 300 new suits, 100 pairs of shoes, 50 leather coats, and 25 hats. Fisher became something of an "every man" in the drug trade.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

If Nicky Barnes had shown what happens when you poke the bear, Fisher was attempting to stay out of the woods entirely.

Harlem was in a transitional period. One of the stalwarts of the community — albeit a notorious one — was gone, and a shining beacon of hope — The Apollo Theater — was shuttered after the 1,600 seat venue had fallen into disrepair.

Even with the doors closed, Harlemites swore they could still hear the crooning from legends who graced the stage like Charlie Parker, Dinah Washington, Bojangles Robinson, Bessie Smith, James Brown, Pigmeat Markham, and Lady Day. The venue remained a symbol for Harlem's resilience; during the riots of 1935, 1943, and 1966, not a single windowpane was broken.

The owner at the time of its closing, Robert Schiffman, believed that the venue was too small to compete with what Las Vegas had created. He planned to increase the size by 2,400 seats, add a 400-room hotel, and a rooftop bar called The Cotton Club — rebranding as The Savoy. The estimated price for the renovation was $30 million.

The Theater briefly reopened in 1978 under new management with shows by Ralph McDonald, War, the T-Connection and Sister Sledge, James Brown, Bob Marley, and Parliament Funkadelic. However, no one was quite clear who owned the legendary theater. According to lore, it was Guy Fisher. According to property records, the Apollo was purchased by the 253 Realty Corporation, and Elmer T. Morris signed the mortgage.

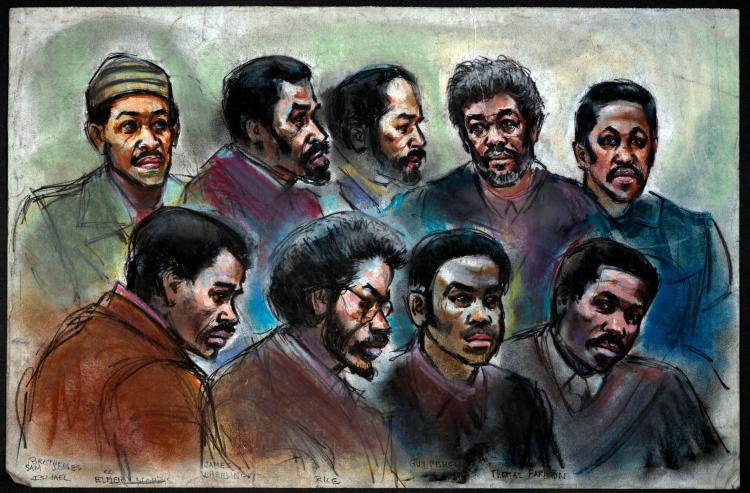

Elmer T. Morris was Guy Fisher's step-brother, and a former Tuckahoe, New York police officer responsible for providing The Council with information about suspected police informants. A courtroom sketch from 1983 shows Elmer "Coco" Morris seated two seats from Nicky Barnes (with Fisher back right).

It's unclear why Fisher didn't want his name on the lease. On one hand, it shows a level of restraint to keep his name off official documentation. On the other hand, his decision to buy the Harlem landmark seemed to evoke shades of Nicky Barnes who created a Harlem mythology by giving away turkeys during Thanksgiving.

The omission of 253 Realty Corporation from the Apollo Theater's website suggests the organization doesn't want to draw attention to this period — despite every other owner dating back to 1938 being listed. But for the years 1978 to 1981, it's like the lights went out even though the marquee was emblazoned.

Guy Fisher and Nicky Barnes represent two examples of cause and effect. When Barnes became a confidential informant, he revealed that Fisher and Samuel Jones were involved in the murders of Oswaldo Peterson and Oscar Wilson who were "terminated" at a Harlem nightclub when Council members suspected the pair of trying to infiltrate the group.

In passing sentence, Judge Pollack said that Mr. Barnes's testimony was ''convincing, devastating and indeed shocking.''

He sentenced four defendants to life without parole for their convictions on the most serious narcotics charge - operating a continuing criminal enterprise. Fisher and James, each received life without parole and 40 years. Morris got 51 years plus $50,000 on the narcotics conspiracy and racketeering convictions. The assistant U.S. attorney said the racketeering convictions against all the defendants included the charges of at least 10 murders carried out by The Council.

Unlike Barnes, Fisher refused to cooperate with the government.

“I never even gave that guy Nick a second thought," he said. "I didn’t have to sneak out a back door. I paid the price, and I had to pay.”

Fisher served 38 years of a life sentence without parole imposed in 1984. In 2020, he argued that his age, health conditions, and the danger posed to him should he contract COVID-19 while in prison — in conjunction with his decades of work to rehabilitate himself — made him a candidate for a sentence reduction. During his incarceration, he became the first and only inmate in the history of State or the Federal Prisons to receive four degrees while incarcerated (Associate, Bachelor, Master and ultimately, PhD in Sociology, 2008). Fisher's motion for compassionate release from Yazoo Mississippi Federal Prison was accepted by Judge Paul Grotty, and his sentence was reduced to time served.

"I quit the streets when I purchased the Apollo Theater," Fisher said during his first interview after being released.

When the Apollo was refurbished in 2001, the architects found that the façade’s upper stories were held together mainly by inertia. The ridged terra cotta had been painted and partly gilded in the 1980s, and behind the paint, there were holes and cracks, and all the mortar had powdered out. But the bricks...they were just fine.