Ernie Paniccioli: Your Favorite MC's Favorite Photographer

Ernie Paniccioli: Your Favorite MC's Favorite Photographer

By Alec Banks

Published Wed, April 21, 2021 at 3:06 PM EDT

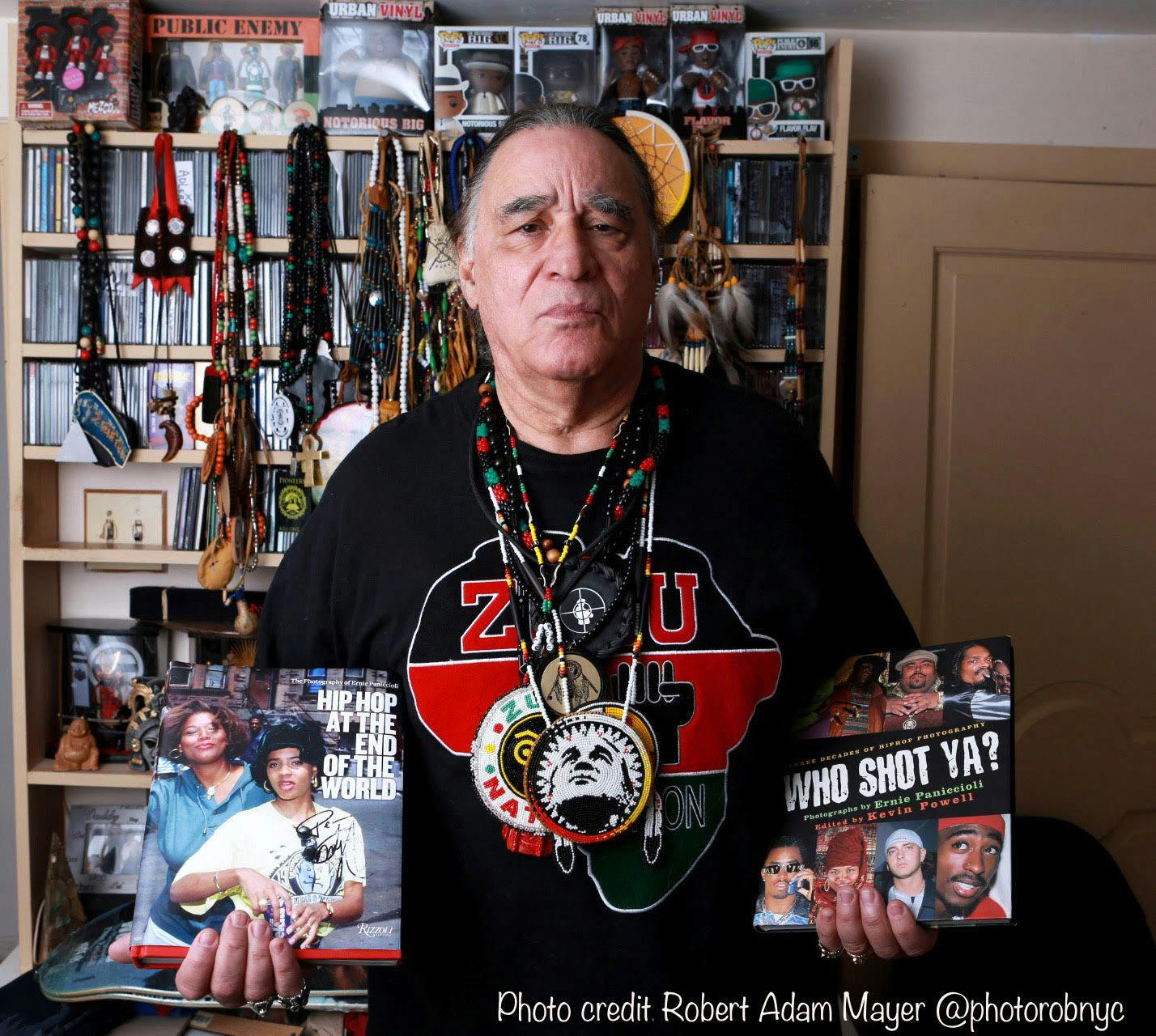

Ernie Paniccioli likes to be called "Brother Ernie."

For those who have had the opportunity to meet the hulking figure — both in physical stature and based on the strength of his body of work — the "brother" part actually comes off the tongue quite naturally. There's a familiarity in speaking with Paniccioli — as if he's a long lost relative with whom you share countless memories with.

And then it clicks.

Since Ernie Paniccioli's photographs are embedded in the DNA of Hip-Hop culture, he's everyone's blood relative.

Paniccioli was born in Brooklyn, New York on February 26, 1947, of Cree Native American and Italian parents. As a kid, life was difficult fo his mother and two brothers.

They were on welfare, and Paniccioli thought it would be in everyone's best interest if resources were split amongst three instead of poor. So he made the decision to lesson the burden on his mother.

"I don't know how she made impossible decisions," he says. "Like do you pay rent, or do you buy food for the kids? So I left home in 1961 so there'd be more money for them."

He spent his teenage years in Greenwich Village immersing himself in the local scene which he describes as made up of, "artists, musicians, visionaries, and miracle workers."

"People who believed that there's more to life than drudgery."

Despite being broke and often homeless, the 74-year-old Paniccioli reflects on this period with gratitude and happiness. There was real power in not longing for creature comforts that others often pined for.

"Miles Davis would be walking down the street," he says. "You might wave at him, if you're lucky he'd wave back. You might smile at him, if you're lucky, you'd get a smile back. The people that were going to shape what culture is in America, were [all] there.

In 1965 — at 18 years old and one day — Paniccioli enlisted in the Navy. While some were drawn to military service as a way of serving one's country, he saw it decidedly different.

"I didn't see it as serving my country. I saw it as escaping what to me had no bottom."

The recruiter pitched him on the ability to see the world. However, as Paniccioli tells it, he also had an ulterior motive.

"My recruiter had two beautiful daughters, one of which, had I stayed there, me and him would not have gotten along. And he knew that. He didn't know that we were already tight. But he wanted to get me out of Brooklyn, out of New York, and out of the Country, as quick as possible. He gave me the highest recommendation, that is possible for a recruiter to give somebody."

Paniccioli did his basic training at Great Lakes Naval Station — just outside of Chicago — before ending up in Norfolk, VA. He spent his time in the Navy working with analog computers on guided missile destroyers.

When Paniccioli returned to New York City he saw firsthand how Hip-Hop culture had permeated every crack. While he had no formal photography training, he felt compelled to pick up a camera. He — along with other first generation photographers documenting Hip-Hop culture like Joe Conzo and Jamell Shabazz – were there for some of the most important moments. While one might expect there to be a rivalry amongst between the photographic Hip-Hop hydra, Paniccioli tells a different story.

"I won't even say brothers. I think we're closer than brothers. there was never a sense of competitiveness. If anything, there was a sense of affection. There was a sense of brotherhood."

There's a saying in the photography world: The best camera is the one you have on you. It's so simple, yet so profound. Paniccioli credits many of his legendary photos to his ability to simply get into functions.

"[Security] knew I wasn't going to be getting into a fight, because I'm trying to talk up some girl, with her boyfriend there," he says. "I'd go in to work, and there would be no problem. That's the secret sauce. had another trick. And this worked, and this is for all you young photographers. A bunch of knuckleheads come up, and they've been drinking for two hours. You know, 'Take my picture MF.' Now, what do you do? Tell them to screw off? Tell them, 'I don't take pictures of punks, or nobodies?' Or you say, 'Okay cool,' and then you take a couple of pictures. They could be your best friends, if something pops off in that club. Because they'll come back, and they'll say, 'Hey, he was nice to us.' Plus the next time I go to the club, there might not be three of them, there might be 10 of them. So, I would always take their picture. And smile. And respect them."

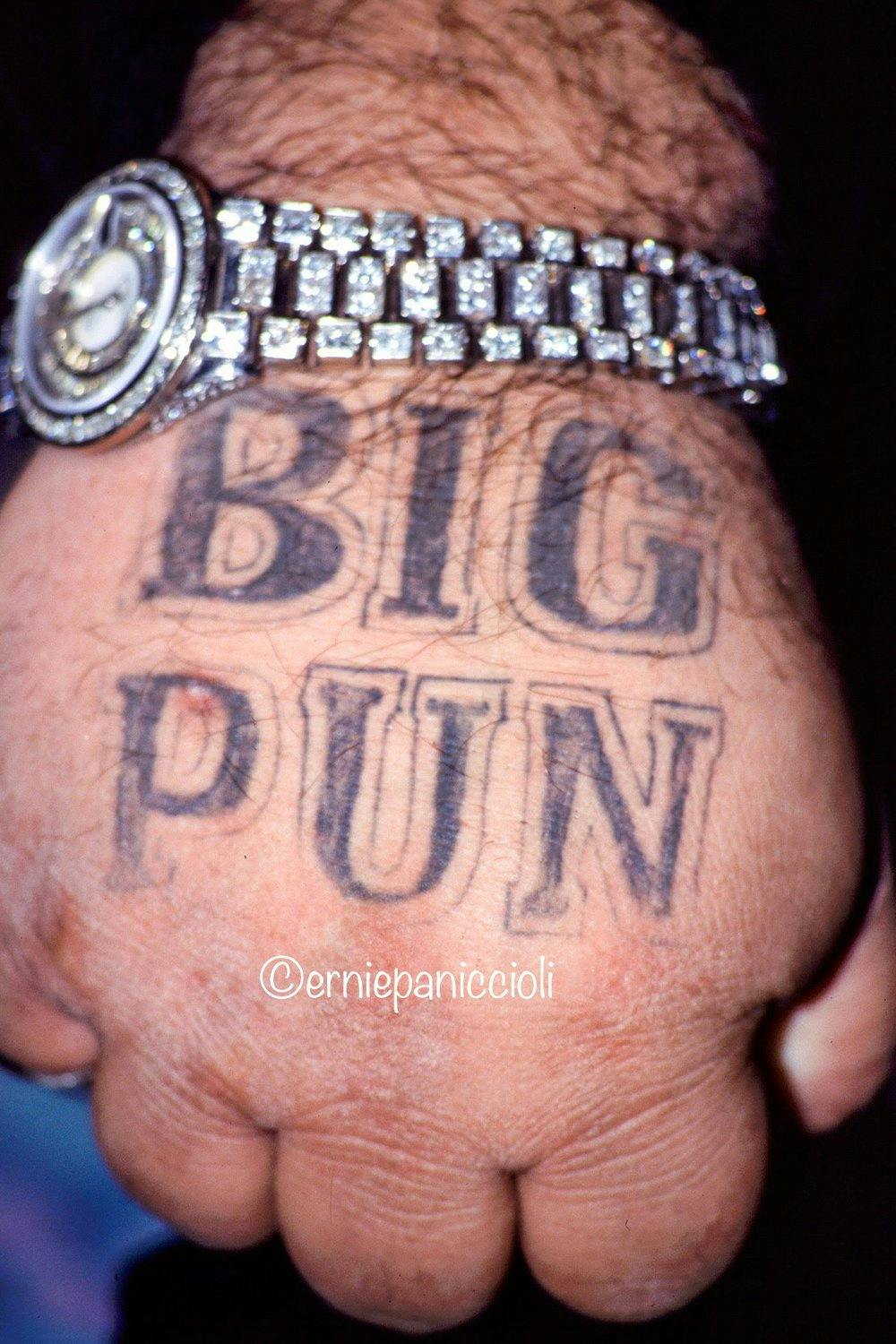

These are simply Paniccioli's tricks of the trade. All of his learnings occurred first hand in the heat of the moment. He specifically cites a time at the Apollo Theater when he was documenting a Big Pun, Raekwon, and Guru performance as an example of how kindness was a more important tool than anger.

"This throng of knuckleheads tells me, 'Get the... out of here!' And I said, 'Excuse me?'one of them pushes me."

"And I had my man with me. There was like seven of them. But we're at the Apollo. The Apollo's sacred. There are a lot of young people there. And inspiration came to me. And during the break, I asked the leader... The obvious leader, because he had the biggest mouth. I said, 'Do you have a sister?' And he says, 'Yeah, why?' I said, 'When you were a kid, did you have posters on your wall?' He said, 'Yeah, why?' I said, 'I shot those pictures.' I said, 'When your sister was mad, did she tear them pictures off the wall?' He says, 'Yeah, how did you know?' I said, 'I've been around a while.' And he looks at me, he stands up. I thought he was going to punch me. He looks at me, and tells his gang, "See that guy? Surround him, don't let nobody mess with him. Let him take his pictures.'"

People responded to Paniccioli's grace and kindness. As a result, he was able to see sides of artists that might not be consumer facing.

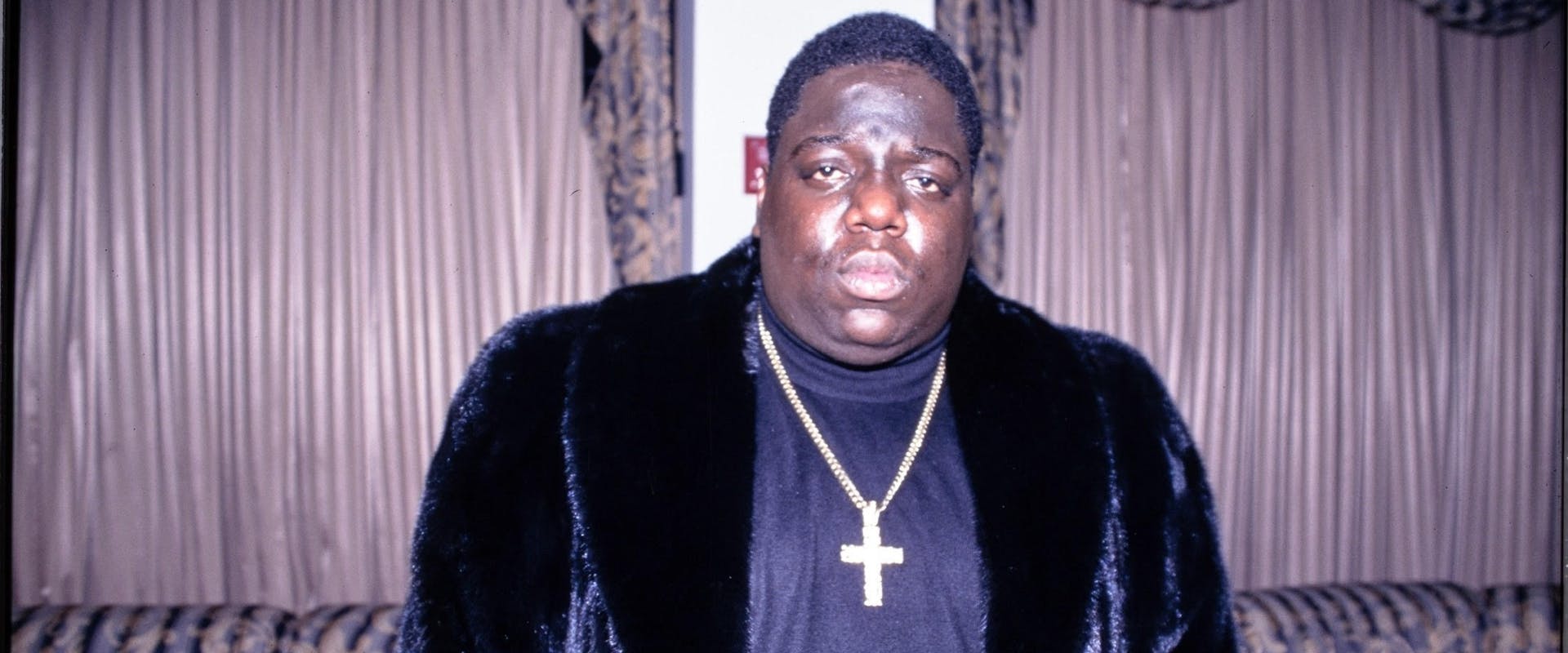

"Biggie would hide my camera bag," he says. "And I'd go out for a minute, come back in the room, and my bag's missing. And I said, 'Biggie, where is my bag?' He'd curse. He'd say, 'I'm a rapper, not a bag holder. Why, because I'm Black, I've got to hold your bag? Who do you think my name is, 'George?'" And he'd go through this whole thing. And he'd step to me. And then I would look him in the eye, he'd break up laughing, and he'd point under the couch.

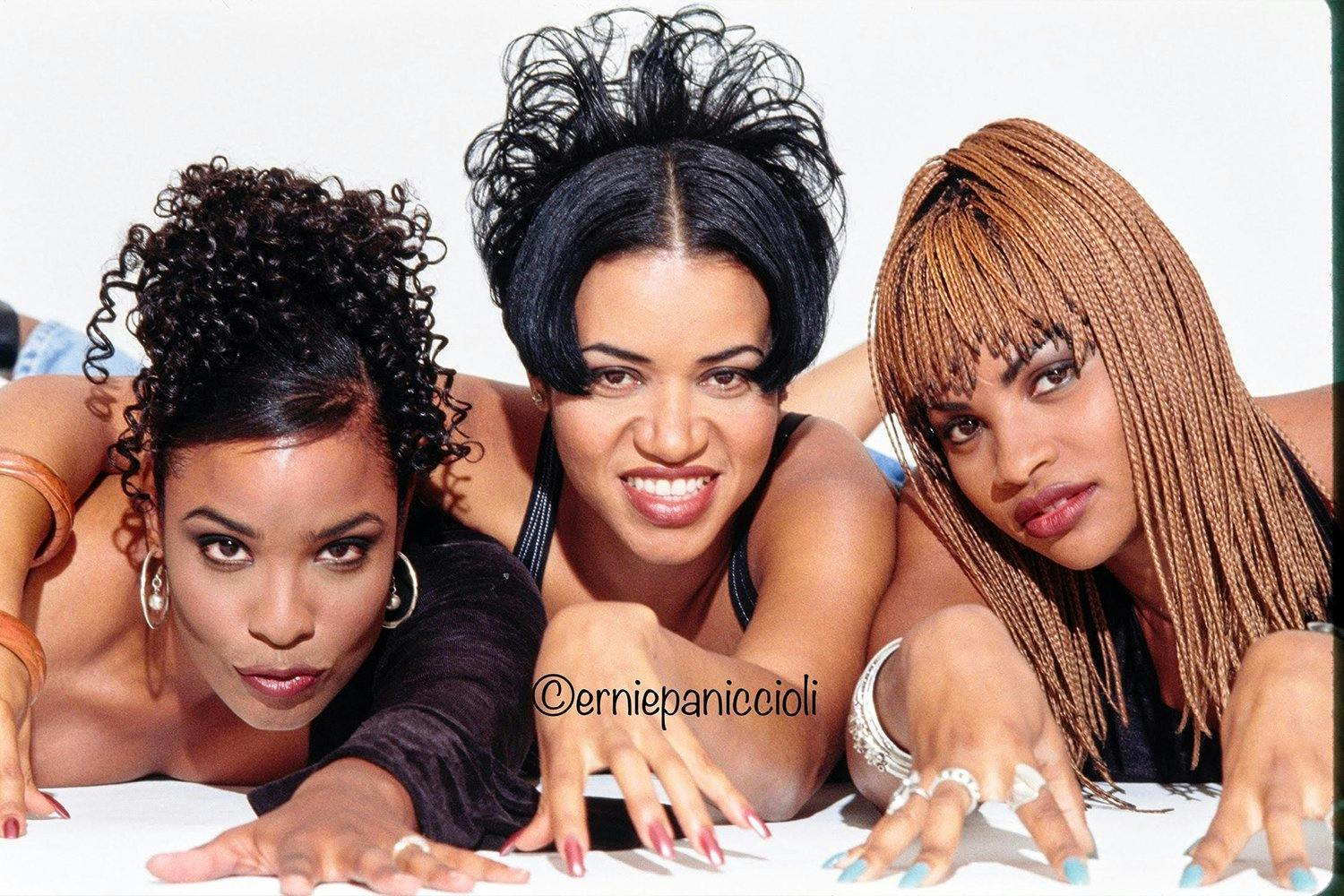

With the ability to make artists comfortable, Paniccioli even crafted an aesthetic that was inspired by baby photos taken at Sears.

"I told Naughty by Nature I wanted them to lay on their stomachs. and Treach looked at me like I was crazy but he trusted me. I said, 'One of the things that I don't like about your pictures is you're always looking tough. You've got beautiful faces. Nice cheekbones, nice features. Lay on your stomachs and look at me the way you would if you were trying to talk to a woman.' It's just the three of them, looking incredibly vulnerable, and incredibly real."

Ernie Paniccioli's entire photo archive can be see for free at Cornell's massive digital library. For fans of the culture, it's not only a trip down memory lane, but it's a testament to the career of one of Hip-Hop's finest. He wants those who look at his pictures to understand an important aspect of how he approached his life's work.

"Blues came from the slaves," he says. "Reggae came from shantytown. And Hip-Hop came from people who had nothing. And I came in. And I tried, because I made a vow early on, that when I photograph people, I would find the god in them. The beauty in them. The royalty in them. And I kept that promise for 40 years. Because when I was a kid, the only time you saw anybody Hispanic, or Native, or Black, or brown, was either in handcuffs, or acting like, "Yes Ke-mo sah-bee, no Ke-mo sah-bee."