The "Cowboys" Who Kidnapped The Biggest Drug Dealers In NYC

The "Cowboys" Who Kidnapped The Biggest Drug Dealers In NYC

By Alec Banks

Published Wed, May 18, 2022 at 12:45 PM EDT

"We got stick-up kids, corrupt cops, and crack rocks." - Inspectah Deck "C.R.E.A.M."

Michael K. Wiliams' portrayal of Omar Little on The Wire was eye-opening on numerous levels. The street savvy Little took from those who couldn't turn to the police — evoking the rebelliousness of the Wild West — when vigilantism pitted the outlaw steel, against the supposedly heroic brass of law enforcement.

According to Williams, the character was modeled after Donnie Andrews, who began robbing Baltimore' drug dealers when he was still a teenager. Although one might hope that Andrews was motivated by a Robin Hood-esque spirit — in which excess was punished by a justified taxation — history tells us that greed was more of a motivating factor than chivalry ever was.

Hip-Hop has added, analyzed, and dissected the motivations of both the stick-up kid, and the drug dealer. In this often deadly game of cat and mouse, the police are characterized as neither a deterrent, nor a purveyor of justice. They're something akin to throwing water on a grease fire: a snap to judgement the exacerbates the situation. As a result, this has led some to label the New York Police Department as, "The Biggest Gang in the City." Additionally, this also suggests that having a badge gives one the opportunity to execute the perfect crime.

And as history tells us, something like this did, in fact, happen.

On February 27, 1991, New York City Police Officer Brian Walsh received a radio transmission that suspicious men were parked outside of a residence located at 6332 Carlton Street, in Rego Park, Queens.

The occupant, Jorge Davila, had been the victim of an invasion robbery several months earlier, and feared that the parked car was full of the type of men who treated locked doors like ATM machines — where one swift kick from a 40 Below Timberland boot — was as good as punching in a pin number.

Officer Walsh observed a Buick containing three males parked in front of a fire hydrant. He approached and asked the driver, David Cleary, for registration and insurance documents. Cleary said that he had borrowed the vehicle, and that he did not know who owned it.

Simultanously, something shiny in the backseat caught Walsh's partner's eye. It was metallic, but most assuredly, not loose change splayed out on the uphosltery.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

It was a bullet.

With guns drawn, they ordered Louis Ruggiero Jr. — all 6'8" of him — and Albert Van Dyke, out of the car. A search of the vehicle unearthed a loaded .357 Magnum under the front passenger seat, a walkie talkie, rolls of duct tape, and plastic handcuffs.

While the officers dealt with the Cleary vehicle, a second Buick rolled down the block. Walsh noticed that it had a similar temporary registration sticker in the windshield, and that the license plate was only four digits "off" from the first Buick. Coincidence? Perhaps. But Walsh decided to play out his hunch and ordered the second car to stop.

The second driver, Richard Olivieri, also stated that he had no paperwork concerning the vehicle, and that a friend owned it. When he was frisked, they found a fully loaded Glock semi-automatic handgun in his waistband. The passengers, Robert Aulicino Jr. and Michael Palozzolo, were also taken into custody.

There was a similarly alarming discovery in the second Buick, too: a .45 caliber semi-automatic handgun, a .357 magnum handgun, a walkie talkie which corresponded to the walkie talkie found in the first Buick, two police shields, and a pair of handcuffs.

Based on the addresses on their ID cards, all of the detained men seemed to come from different parts of the Tri-State area. Some were from the Bronx, while others were from New Jersey, Westchester, and Rockland Counties. Yet, circumstance — and perhaps opportunity — had brought them all together on an evening that would ultimately expose the DNA of one of the most ambitious and audacious kidnapping schemes ever.

There's an exchange in the film Training Day between Detective Alonzo Harris (Denzel Washington) and Jake Hoyt (Ethan Hawke). Harris instructs Hoyt to, "Tell me a story." Hoyt proceeds to detail a seemingly innocuous DUI stop where he and his partner discovered a loaded .38 and two shotguns. As it turned out, the driver was out on bail for drugs, and on his way to kill his ex-partner.

"We prevented a murder," Hoyt boasts.

Officer Walsh surely thought to himself, "What did I just prevent from happening?" And moreso, "Why do these men have police shields?

By the late 1980s, the NYPD was failing to combat the open-air drug market despite enacting menacing "teams" like the Tactical Narcotics Team, or T.N.T, who formed as a response to the execution-style slaying of a rookie police officer, Edward Byrne, in 1988.

''Drugs - it's all over the place,'' said Edward McCarthy, a spokesman for District Attorney Robert T. Johnson of the Bronx. ''It's incredible; they are selling the stuff right around the courthouse.''

Before the 117 person T.N.T. unit was formed, felony drug arrests were already overwhelming the city's criminal justice system. The police made more than 90,000 narcotics arrests in New York City. Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer found a metaphor. He said it was like a balloon filled with water: ''When it's squeezed on one end, it expands in another.''

With two ounces of cocaine, two more ounces of "comeback" — ' a chemical adulterant akin to lidocaine — one ounce of Arm & Hammer, and a little water, a dealer could cook and distribute 2,000 vials of crack at between 4-$10 a vial.

By the mid-1980's, cocaine was arriving in New York by the ton through Colombia's Cali Cartel. The Dominicans became New York's chief middlemen, and the city was eventually carved up along ethnic lines — with Black dealers controlling Harlem, Queens and Brooklyn — and the Dominicans dominant in upper Manhattan and the South Bronx.

According to New York State statistics, there were 182,000 regular cocaine users in New York City in 1986. That number grew, to an estimated total of 600,000 in 1988, most addicted to the popularity of crack which bore the street name "Scotty" because the effects "beamed" a user up.

Colombia produced the snow, New York City cooked it into rock, and a group of "Cowboys" believed they could add to the recipe.

In 1990, members of the Bronx Major Case Squad first heard rumbling that there was a group of men posing as cops in order to rob drug dealers.

"People were telling us, 'The guys who took my friend out of the store in handcuffs were cops,'" said Police Captain Robert Martin, who headed up the investigation, along with Sergeant Vic Cruz.

Martin and his squad of detectives had little to go on at the time because the targets of the kidnappings wanted nothing to do with the police — thus making it a seemingly victimless crime. However, there was a pattern of strange occurrences that they slowly began piecing together.

Otmar Delaney ran an active drug business and numbers operation out of a garage in Harlem in the early 1990s. On one occasion, he was followed to his home in Yonkers by three men. They identified themselves as police officers and placed him under "arrest." It wasn't until two of the men jammed a befuddled Delaney in the trunk of their car that he suspected anything was wrong.

Delaney was driven to a dingy, Fort Lee, New Jersey motel twenty minutes away from Yonkers. His captors. Steven "Pooh" Palmer, Ruggiero, and someone only identified as "Tommy," took turns torturing him with a staple gun until he agreed to get $750,000 in cash from his half-brother.

For a brief moment, he was left alone in the room while Ruggiero stepped outside to use a pay phone, and "Tommy" agreed to get him some water.

Delaney, still handcuffed to the chair, escaped from the room, and was able to explain what happened to a truck driver who was standing in the parking lot. The two went to the motel manager's office to call the police, but when Delaney saw Ruggiero, he stole the truck driver's rig.

Chaos ensured. With one hand still handcuffed to the chair — and with the truck driver clinging to the side of the truck — the stolen bogie eventually collided with two other vehicles and came to a stop. By the time the police arrived, the kidnappers were in the wind.

The brazen kidnappers made new attempts to extort money from Delaney. These post-kidnapping extortion attempts apparently ceased when Delaney, with a false promise of payment, lured the kidnappers to a meeting that ended in a shootout.

Despite the botched Delaney kidnapping, the would-be-opportunists wouldn't be discouraged. Shortly after Christmas 1990, Ruggiero, Cleary, Castelli, Olivieri, and Palazzolo met outside of a laundromat owned by Alvin "Butch Cassidy" Goings. Goings was an alleged member of the 142nd Street Lynch Mob with notorious members like Charles Leon Brown, Ferris Phillips, Louis Griffin, and a ruthless enforcer nicknamed "Homicide Lou." He was the most high-profile target to date.

Goings was "pulled over," handcuffed, and placed him in an awaiting van. And this time, it worked.

Members of the gang were told that the ransom payment was $400,000. Some crew members believed, based on neighborhood rumors, that the payment might have been as high as $1 million.

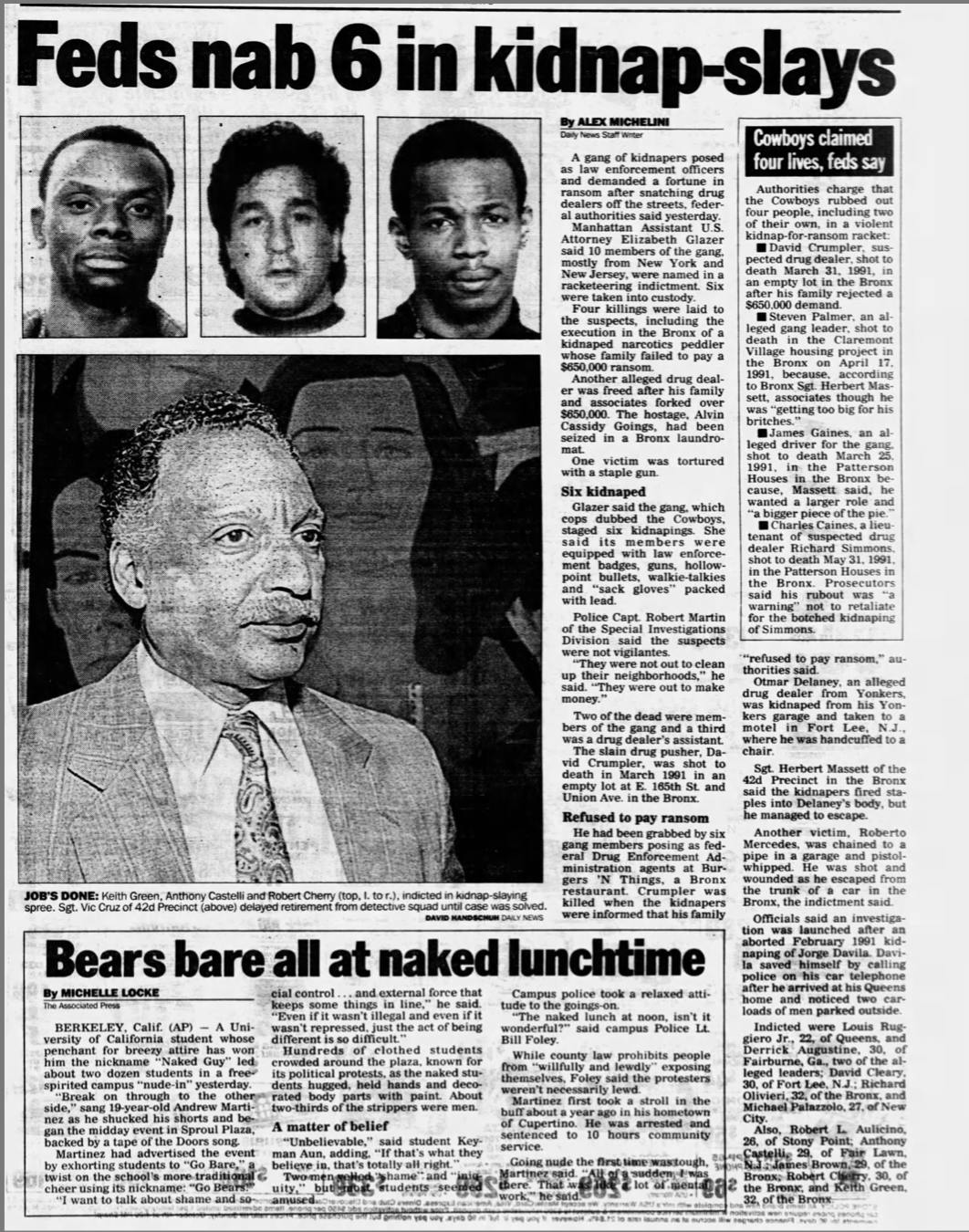

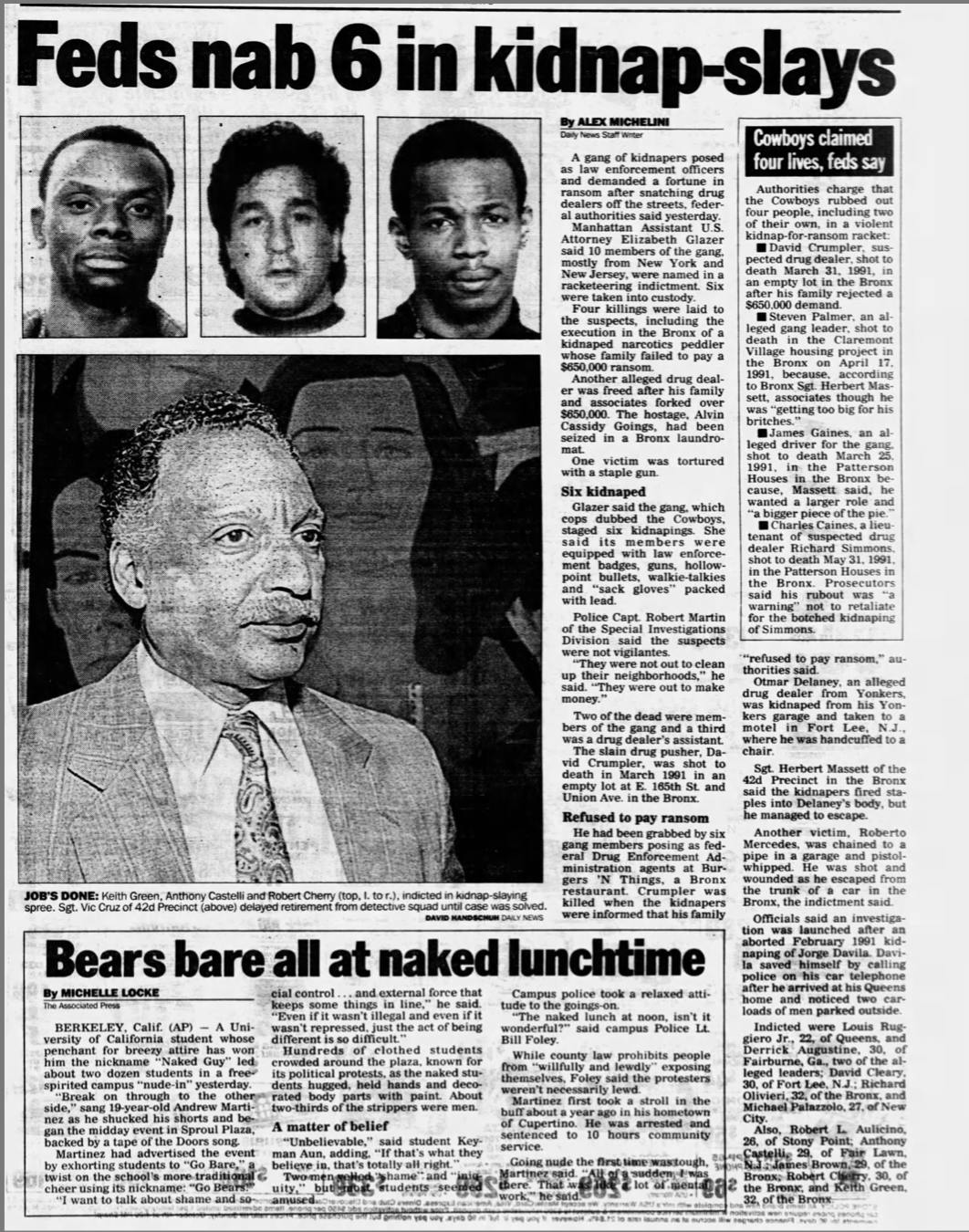

There were three more attempts on known drug dealers between January and March 1991: Roberto Mercedes, Richard "Fritz" Simmons, and David Crumpler. The latter, a restaurant owner who dealt cocaine in the Bronx, was taken in handcuffs at Burgers 'N Things to a nearby gas station. Some hours later, Crumpler's wife received a ransom demand for $750,000. Despite torturing Crumpler with a blackjack, stun gun, and staple gun, Ruggiero, Cleary, and Castelli were unable to get Crumpler, or his family, to pay the ransom.

Crumpler's handcuffed corpse was found in a vacant lot in the Bronx at E. 165th Street and Union Avenue.

On April 17, 1991, officers from the 42nd Precinct reported to what appeared to be a gangland murder on 1260 Webster Avenue next to the twenty-one story Webster Houses. There was a dead body riddled with 13 bullet holes lay splayed to a white Nissan Stanza with a blown out driver's side window. The victim was Steven "Pooh" Palmer.

Six days later, Operation Hercules was established in an attempt to understand the connection between the kidnappings, robberies, and murders, of several high-profile drug dealers in the Bronx. The first domino to fall was Albert Van Dyke, who was being held for his involvement in a kidnapping of an underworld banker in Queens.

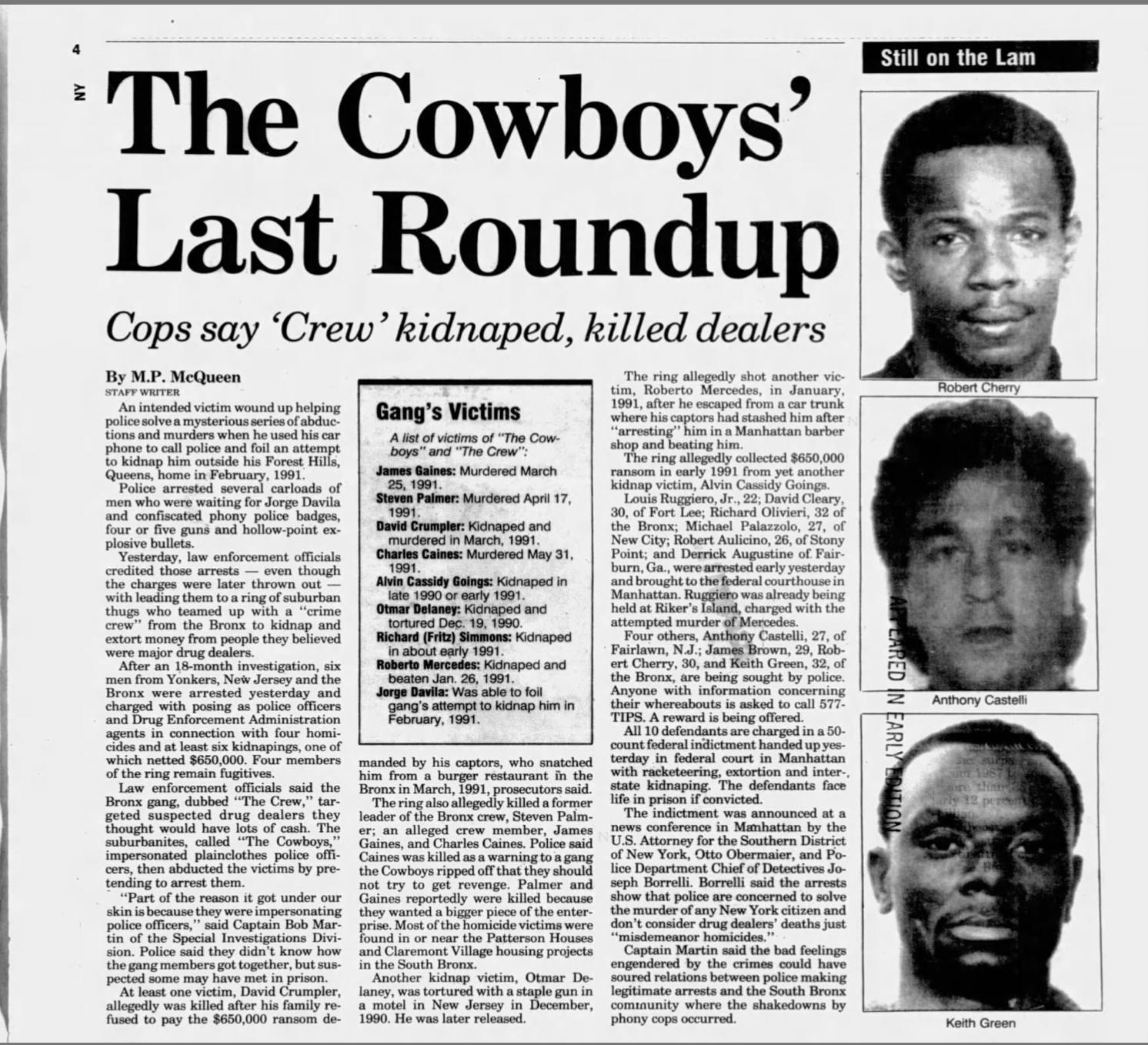

The conspiracy involved two different skill sets: the "Crew" identified drug dealers who were primed to be robbed — some of whom they had done business with. The "Cowboys" were the men responsible for impersonating police officers and the kidnapping. According to Van Dyke, Palmer and Ruggiero were the tip of the spear when it came to the Cowboys.

The first wiretap order for Cleary's telephone was issued on the basis of an affidavit executed by Investigator John J. Maurizi of the Bergen County Narcotic Task Force on April 25, 1991. After reviewing Maurizi's affidavit, Judge Grossi issued an order authorizing the interception of communications over Cleary's telephone for a period of twenty days.

A wiretap intercepted anxious conversations between Ruggiero and Cleary speculating that Delaney might have killed Palmer, and between Cleary and Palazzolo, speculating that Richard "Fritz" Simmons might have done it.

In a May 22, 1991 telephone conversation with Ruggiero, Augustine attempted to encourage the belief that Palmer had been killed by one of the kidnapping victims. In addition, in that conversation, Augustine said, "I'm telling you, we need to get smart, man. One time and then leave this shit alone." Ruggiero responded, "Yup," and, "Maybe we will."

In early June 1991, Cleary was arrested in New Jersey on unrelated state charges, where he remained in jail for at least the next several months. In the summer of 1991, Augustine fled New York, in part, he said, because, "The police was looking for me, because of, you know, the kidnapping and the murder that was going on in the Bronx."

Cleary shared a cell with Vincent Moscatello in a Bergen County, NJ jail. Although they were strangers, they had several mutual acquaintances — including Castelli and Palazzolo. He felt comfortable enough with Moscatello to reveal that his group, "would arrest them, make like they were the cops," and then "would hold them, bring them someplace, hold them and they would, they would get somebody to call from that individual, to call for ransom."

The ring targeted 10 victims and expected to receive ransoms of a million dollars from each victim. Cleary said he had not participated in the ring's first kidnapping, which Ruggiero had botched:

"Louie [Ruggiero] had did a kidnapping first," Moscatello would later testify about Cleary's admission. "David didn't want to get involved at first. Louie had did the kidnapping on his own, and he had a little trouble with it. He was on the phone making a phone call to the family, and the victim that he had in the hotel was handcuffed to a chair, went running down the block past him as he was on the phone calling the person's family."

According to the government, on December 9, 1992, Derrick Augustine and his lawyer, Wesley Serra, met with the prosecutors to discuss the possibility of cooperating. He told investigators that his co-defendants, who were incarcerated with him at FCI Otisville, had solicited his help in locating Roberto Mercedes, one of the alleged enterprise's kidnapping victims.

They told Augustine that they wanted to bribe Mercedes so that he would not testify in the event of a trial. If Mercedes refused, Cleary, Ruggiero, and Palazzolo said they would arrange to have him killed.

On another occasion, Cleary told Augustine that he was reluctant to kill Mercedes because there were already "Too many bodies in the case."

On April 1, 1993, the government charged Ruggiero, Cleary, and their co-conspirators in a fifty-nine count indictment with participating in a kidnaping ring that operated from 1990 to 1991 in New York and New Jersey.

Olivieri, Palazzolo, Castelli, and Augustine pled guilty to various counts prior to trial. Brown, Green, and Cherry were fugitives at the time of trial but were later apprehended; Brown and Green pleaded guilty to the RICO conspiracy count.

In addition to the murders of Crumpler and Palmer, the ring was accused of murdering two more men: James Gaines, an alleged driver for the group, who was murdered March 25 in the Patterson Houses for wanting a "bigger piece of the pie," and Charles Caines, a lieutenant of Richard "Fritz" Simmons, who was shot to death May 31, 1991 in the Patterson Houses. The latter was supposedly killed so as to avoid any retaliation for Simmons' botched kidnapping.

"They were not out to clean up their neighborhoods. They were out to make money."

- Captain Robert Martin

Ruggiero, Cleary , and Aulicino were tried in a seven-week trial before an anonymous jury. Ruggiero and Cleary were convicted of, RICO substantive and conspiracy offenses; various RICO-related offenses; firearms offenses; the kidnappings of, and conspiracy to kidnap and extort money from various drug dealers.

Aulicino was sentenced 78 months'imprisonment, to be followed by a five-year term of supervised release. Cleary and Ruggiero were sentenced to life imprisonment, to be followed by five years of supervised release.

Today, New York City attempts to curb bad — and sometimes fraudulent cops — with its Group 51 internal affairs unit which was formed in 1994. With a dozen officers, the unit caught 100 fake cops in 2020.