Forever B.A.D.: 19-Year Old LL COOL J Shook and Solidified Rap's Rise

Forever B.A.D.: 19-Year Old LL COOL J Shook and Solidified Rap's Rise

By Kevin Coval

Published Sat, May 28, 2022 at 3:20 PM EDT

In 1987, popular culture in America was beginning to change.

The highest grossing actor that year was Steve Guttenberg (whose Police Academy helped intro the world to the beat-boxing sound effect machine Michael Winslow), but Eddie Murphy and Beverly Hills Cop II was coming for that number one spot. TV continued to fill the countries dreams with Eurocentric visions of hyper-capitalist soap operas like Dynasty and Dallas, but the most watched programs were The Cosby Show and A Different World, both airing, like a promise and reward, on Thursday nights.

In 1987, Magic Johnson finally won NBA MVP, wresting it away from Larry Bird after three consecutive awards for Larry Legend. Michael Jordan had, perhaps, his greatest season ever in 1987-88; and would be crowned the league's MVP in 1988, averaging 35 points per game, the same year of Mars Blackmon commercials and Mike becoming more recognizable than Mickey Mouse. '87 was a giant year for the culture; Paid in Full, Criminal Minded, Yo! Bum Rush the Show, Born to Mack, and Rhyme Pays all dropped.

But 1987 was also the continuation of a giant increase in incarceration rates. Between 1980 and 1989, the U.S. prison population grew by 115% — from 329,821 to 710,054 people — disproportionately effecting Black and brown populations and young men, 15-25, in particular. While Ronald Regan was telling Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev to "tear down this wall" in Berlin, he and Nancy and congress and development companies were building walls, en masse, creating prisons and a privatized growth industry on American soil, in the era of deindustrialization.

The Original Todd, James Smith, chose his nom de gurre as a way to not only allude to his appeal, but also to throw off a stigma associated with the burgeoning art of emceeing. In the pioneering era, MC meant, quite literally, to Move the Crowd. Party-rocking prototypical lyricists helped their DJ transition between records and kept the party going til the break of dawn because of, yes, their calls and response that alerted and kept the crowd on their toes. Many early emcees adopted monikers that referred to the(ir) bacchanalist lifestyle and had more to do with late '70s and early '80s club and disco culture than it did the young, emergent artistic movement. Coke La Rock, Kurtis Blow, the myriad of Skis (that's right, white slopes of white girl), etc.

But there are much larger forces the 19 year-old emcee from Farmers Boulevard was challenging on his second studio record, Bigger and Deffer. The first words of the project's eponymous track, come from someone outside of the community, personifying the real Orwellian threat that Black and brown neighborhoods, like St. Albans, Queens, were being watched and policed in new and insidious ways.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

"Calling all cars / Be on the lookout for a tall light-skinned brother with dimples" the "radio" voice surveys, an immediate commentary and playful resistance to the gaze and yoke of white supremacy.

The first track alone, a wildly inventive, energetic braggadocio (a genre in the poetics of emceeing), places LL COOL J in the conversation of greatest rapper alive in 1987 along with Rakim and KRS-One. "I'm Bad," the continued proclamation, an inversion of a term, used in the moment and historically, to demonize people, stemming from a Christian/Cartesian duality, and used to characterize Black folks, in particular, as a way to justify slavery.

Hip-Hop and Black diasporic linguistic practices such as signifying are, of course, responsible for reclaiming many words utilized in the lexicons of the oppressor and empowering the oppressed with the flip and utilization (see track 5 of Tribe's Midnight Marauders for example). "Bad," the term, was rescued a year earlier on Run-D.M.C.'s "Peter Piper," an ode to Jam-Master Jay ("not bad meaning bad but bad meaning good") and a generation or two prior when jazz writers and musicians began to invert the word, as in a 1927 Variety review of Duke Ellington's band playing in Harlem stating the group "is just too bad," meaning "wonderful; deeply satisfying; stunningly attractive or stylish; sexy" as The Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang says. And it is in all of these arenas, LL COOL J asserts his badness.

Bigger and Deffer is not a political record, per se, but from the album cover to its content, the specter of LL COOL J at this time, in the country's consciousness and schizophrenic history, was a singularity and force to be reckoned with. I mean—Harry Hamlin was on the cover of People Magazine's "Most Beautiful Man Alive" issue in 1987, and here is LL COOL J on his own cover of Bigger and Deffer, photographed by Glen E. Friedman, standing in front of the high school he dropped out of, in a red Kangol and leather pants, staring straight into the stark contrast, draped in impossibly giant truck jewels that gave reverence to both local drug dealers and African kings.

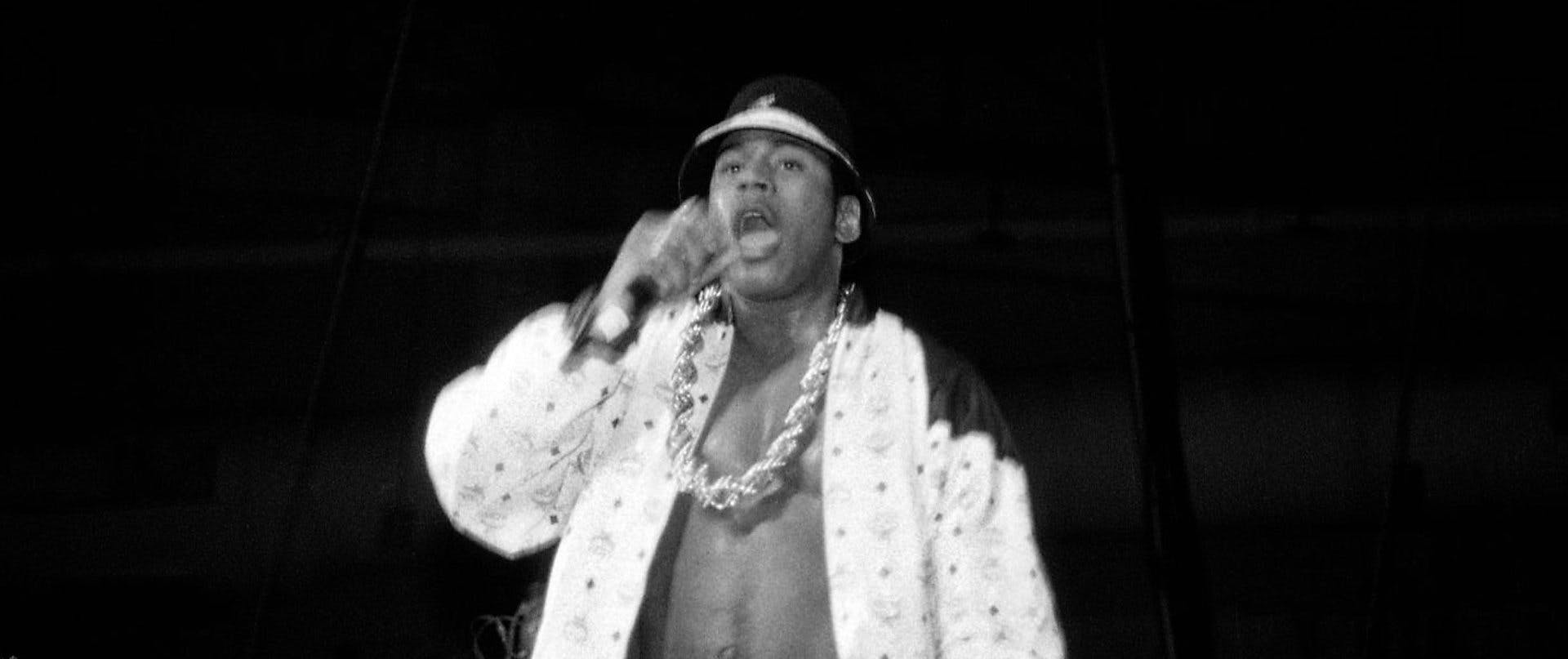

LL COOL J was perhaps advancing the insouciant rebellion of bop, confronting confidently, nonchalantly the bullying pupil of whiteness and European standards of beauty. His gaze directly back into camera and to those watching/policing him and his community is a cool that counters the constrained manicured and manipulated, cropped and advertised images corporate America was selling. A menagerie of teeny bop kids on the block, so as long as the block wasn't anywhere near the corners where young men who looked like LL COOL J stood.

His presence is compounded, in part and because of the success of the crossover rap/R&B ballad, "I Need Love." The song (which, admittedly, I rapped the first verse to Susie Soper sophomore year before she stopped me to say she wasn't interested) and LL COOL J's penchant for taking off his shirt thrust the 19 year-old into rarefied air; becoming Hip-Hop's first global juggernaut and the culture's first international sex symbol. An American Adonis; ladies from all walks of life did indeed love cool James. Making the timing of his stardom striking, juxtaposed against the increasing incarceration and arrest rates of people who looked like and were LL COOL J's age and race. America the complicated; America the contradictory.

"Bigger and Deffer than what?" is certainly implied in the title; which one might level a blue dictum (so to speak), but I think operates as well as an aesthetic assertion vying for the heart of the country. LL COOL J was making the case that this nascent art form, still being introduced to the mainstream for the first time and for years to come, was artistically iller (More powerful? Better? All of the above?) than it's then-more dominant cultural peers. I'm suggesting that Bigger and Deffer is an Ars poetica: proclaiming the arrival and preeminence of the form as high art and pop(ular) music that he "used to rock in my basement / now I'm number one." (The album was #1 for 11 weeks on Billboard's Top R&B chart and #3 on the Billboard 200 and certified platinum in November of that year.)

The emotional and narrative complexity over the course of B.A.D., covers an astonishing range, carving out new spaces for young men, in particular, to be ok with being vulnerable and cool and excellent, all at the same time or at least within the same day. There is a ton of top notch shit talking (something I would argue is a kind of linguistic celebratory practice) and exuberant praise being thrown about this record; LL COOL J loves to show love to his DJ, Cut Creator, his borough Queens, his (future) love (LL COOL J would meet his wife of 25 plus years, later that year), his emcee skills and sex workers, (I think).

This is, after all, an opus from a young superstar, so, as is foundational in the music and culture, you hear a lot of fun on Bigger and Deffer; in a moment, this budding artist is reaching a new level of fame, and his country is also hunting him and those who like him. The grim reality of the Reagan '80s looms over all of these records which is even more of a reason to turn them up and "get down to the rhythm that'll rock the walls" and tear those walls, down, forever ever.

LL COOL J interview from Dec. 19, 1987, at the Tokyo Prince Hotel in Tokyo, Japan