“Despite what’s been written, there were just a handful innovating, setting the stages and spearheading the main elements that became commonplace and followed by the pack. Style just happened to be one of my things. That’s how I functioned in the everyday matrix of life.” — PHASE 2 in IG Times

In early-’70s New York City, writing on walls and trains was a pastime that had a better chance of landing a person in jail than launching a career in the arts. In fact, many of the earliest writers didn’t even consider themselves artists.

In much the same way that Hip-Hop music was thought to be a passing fad, writing was dismissed as urban blight that could be remedied by politicians and MTA workers.

In 1970, The New York Times noted that the New York Transit Authority spent $250,000 to remove vandalism — a figure that would rise to $300,000 and $500,000 in the next two years — until all 6,802 NYC subway trains would be “hit” by 1973.

CREDIT: PHASE 2 AND HERC TAGS/PHASE 2 TAG / PHOTO: MICHAEL LAWRENCE

PHASE 2, born Michael Lawrence (Lonnie) Marrow, was tall and lanky — with an affinity for Italian knits and sharkskin pants. Raised in both Harlem and the Bronx — specifically building 965 in the Forest Houses projects — PHASE was the youngest of three children (two sisters and a brother) born to an African-American mother, Adele, and a Panamanian father, John, whom he lost at a young age. The people who grew up with PHASE 2 remembered him singing in the hallway, with aspirations of being a funk/soul singer.

Like so many other kids of the era, PHASE witnessed firsthand the pitfalls of living inside the low-income residence. While future juggernauts in the Hip-Hop community like Diamond D, Fat Joe, Lord Finesse, and Showbiz channeled this experience into music, PHASE found himself enamored by New York City writing culture.

He began writing in 1971, at a time when writers were armed with markers and spray paint. They performed “single hits” — leaving behind rudimentary tags that usually included a person’s government first name and the street that they grew up on (JULIO 204, TAKI 183, JOE 182).

The very nature of PHASE 2’s moniker (sometimes stylized as PHASE II) suggested an otherworldly, almost superhero-esque quality about him. But unlike Peter Parker turning into Spider-Man, PHASE 2 was consistently in his most elevated form.

“PHASE was a fly dude,” recalls his friend, Adam Mansbach, who first met him in 1995. “He was a flavorful dude. He had style in the way he spoke, the way he moved, and the way he posted up on a corner.”

Admittedly, PHASE 2 would have been against any formal investigation into his life and career. He hated the idea that his personal narrative would ever be in the hands of another person. While his desire for privacy certainly impacted his art career, it was not something that he dwelled on.

“He wouldn’t compromise with what he believed in,” says artist Roberto Gualtieri, better known as COCO 144, an early-’70s writer who called PHASE 2 a friend for over 46 years.

Masterpieces

PHASE 2 / PHOTO: MICHAEL LAWRENCE & HERBERT MIGDOLL/PHASE 2 ON SUBWAY

John Coltrane was able to build upon the improvisational nature of jazz with 1959’s “Giant Steps.” Similarly, early writers like SUPERKOOL 223 took the basic principles of writing and created something more polished and grandiose.

In 1972, the “masterpiece” was officially born — showcasing a sense of artistry in tagging, where the letter form was multicolored and brimming with flourishes.

As The New York Times noted in its January 1973 coverage, “The masterpiece is a large, usually multicolored, inscription, applied on the side of a subway car with cans of paint spray, that may cover half or more of the car’s length. Authority officials say that such works are usually done while the trains lay idle in yards and layup areas.”

Since getting up was — and still is — about one-upmanship, these pieces grew in scale and color, aided by “racking” missions, in which several cans of paint were stolen and used to produce much more vivid abstractions on walls, trains, and buildings.

PHASE 2 was at the forefront of the masterpiece revolution.

He invented a whole menu of signature styles, which he gave whimsical names like “phasemagorical phantastic” (bubble letters with stars), “bubble cloud” (bubble letters surrounded by a cloud pattern), “checkerboard phase phantastic” (bubble letters crosshatched), “bubble big top” (bubble letters with outsized tops), “squish luscious” (swerving, speed-streaked bubble letters), and dozens of others.

“Unlike SUPERKOOL, I took an approach to piercing beyond the signature style and developed mine from simple to more formatted, more diverse, and wilder styles,” PHASE told International Graffiti Times.

PHASE 2’s energy and inspiration didn’t come from other writers as much as his own self-professed “rebelliousness in the soul.” He likened his imaginative state to being out of control and fast-paced — like freestyle dancing in a euphoric atmosphere.

“His lettering constantly changed; you never saw his tag repeat itself,” said Hugo Martinez, the founder of United Graffiti Artists, in The New York Times. “He was constantly trying to destroy himself, destroying his previous style.”

For some, the masterpiece era was proof that there was artistic merit to writing. For others, it was a signal that the so-called inmates were now running the asylum.

PHASE 2 ON SUBWAY / PHOTO: MICHAEL LAWRENCE & HERBERT MIGDOLL

Patrolman Steven Schwartz was three and a half years into his tenure as a transit cop when the masterpiece era blossomed. He took it upon himself to crack down on the writers inside the train yards on 225th Street and 231st Street. Schwartz was first drawn to the assignment a year earlier after witnessing two daring writers leaving their tags behind on the District 4 police station.

“They start out small with thin dry markers, and then they graduate to half-inch marker, and then it’s the big leagues — Red Devil, Rust-Oleum or whatever other kinds of spray paint they can steal,” Schwartz told the New York Daily News.

Writers like PHASE 2, SUPERKOOL 223, RAY-B 954, SWEET DUKE 161, PINTO 168, and KOOL KEVIN I became his sworn enemies. PHASE 2 reveled in the cat-and-mouse game between him and Officer Schwartz.

On one occasion, Schwartz was specifically looking for PHASE 2 when he descended upon a group of six writers. All of them scattered except for PHASE, who casually finished his Carvel’s ice cream cone. He wanted Schwartz to know that he couldn’t be intimidated. But instead of lobbing insults, he used the pen like a sword — leaving behind a poem for Officer Schwartz.

“If you only knew / the real PHASE 2 / the super sleuth / who’s still on the loose / you caught Cool T/ but you didn’t catch me / I got away while eating / my vanilla ice cream.”

PHASE 2’s masterpieces were revolutionary because they shifted the notion that writing was a game of repetition. While others worked diligently to make their tag consistent and repeatable like the Coca-Cola formula, PHASE enjoyed the experimental aspect of the art form.

“One of his main contributions was he was into evolution,” says ’70s-era writer VULCAN. “Things don’t stay the same; we can change them. When his pieces rolled by, you’d want to watch it every day because he was doing something different.”

Writers Corner 188 & UGA

In 1972, Hugo Martinez, a City College student majoring in philosophy, would often pass through the 91st Street Station when he was coming down from school. The names scrawled on the tunnel walls left him with more questions than answers.

As a scholar, Martinez had spent time examining gangs of the era, like the Savage Nomads and the Young Galaxies. He understood quite clearly that there was something different driving these writers beyond just marking their territory.

He eventually approached the teenagers on WRITERS CORNER 188 in Washington Heights — the preeminent meeting point for writers of the era. The spot itself bumped up against a five-story building with a six-foot-deep alley running around it.

Martinez offered these kids an alternative to writing in the streets — a space at City College to ply their trade as artists. With this promise, he was able to recruit some of the best writers in the city, including SNAKE 1, SJK 171, MIKE 171, STITCH 1, HENRY 161, WICKED GARY, BAMA, COCO 144, and PHASE 2. Following his vision, he organized them into a formal collective, United Graffiti Artists, which came to be known as UGA.

“I started United Graffiti Artists in 1972 as a collective that provided an alternative to the art world,” Martinez told New York magazine. “I saw this as the beginning of American painting — everything else before this came from Europe. These kids were rechanneling all of those hippie ideas about freedom, peace, love, and the democratization of culture by redefining the purpose of art. They represented a celebration of the rights of the salt of the earth over private property.”

PHASE 2 ON SUBWAY / PHOTO: MICHAEL LAWRENCE & HERBERT MIGDOLL

As word spread that an indoor space existed at City College that provided paper, spray paint, and markers, other writers from Brooklyn and the Bronx were inspired to join.

Martinez urged PHASE 2 and his fellow UGA members to create canvases for a proper gallery event. In December 1972, City College hosted the first official UGA show, featuring a group work on a single 10-by-40-foot wall canvas.

As important a moment as this was in raising the profile of these writers to the level of artists, it also fostered a spirit of collaboration — and lifelong friendships — among them. Unlike relationships that involved a building up of trust, COCO 144 describes his connection with PHASE 2 as instantaneous.

“You meet someone and you know they’re going to be your friend forever,” COCO recalls. “We jived like that. He just had this really beautiful energy.”

Herb Migdoll, an arts photographer who attended the inaugural City College show, pitched the idea of bringing UGA’s work to the Joffrey Ballet. In March 1973, 18 UGA artists painted a rolling backdrop on stage during the ballet’s production of Twyla Tharp’s Deuce Coupe, which mixed classical choreography and the songs of the Beach Boys. The show’s program thanked Martinez and artists like PHASE 2, SNAKE 1, STITCH 1, COCO 144, and others for their contributions.

The New York Times noted in its coverage, “Early in the work, six genuine graffiti artists with spray cans come on to do their stuff on three panels downstage. Perhaps unintentionally, ‘Deuce Coup’ is about co-optation. Without being romantic about the frenzy of graffiti that burst upon the city, it is illuminating to find that their creators are now apt to perform onstage for others rather than just for themselves. Similarly, the Beach Boys — with their affluent images of sun, surf and cars — are a reassuring transmutation of the working‐class rock that preceded their rise in the sixties.”

The pinnacle of UGA’s success came on September 4, 1973, at Razor Gallery in Soho. The exhibition, “The Best of M.T.A.,” boasted 20 former — and active — subway writers. The show’s highlight was a 30‐foot collaborative mural bearing the names of more than a dozen artists — including SNAKE I, STICH, SPANK, SJK 171, COCO 144, AMRL, C.A.T. 87, MICO, PHASE 2, T-REX 131, FLINT 707, and BAMA.

“PHASE would come back and highlight something for someone else, and then someone else would do something around him, so there was ... I’m not going to say it’s hard to describe in words,” remembers COCO. “It’s just this experience, living this, that moment was like the perfect song. It’s like the perfect beat on that drum.”

Writing in The New York Times, critic Peter Schjeldahl singled out one of PHASE 2’s canvas works: “PHASE 2’s name is couched in fat, sensual, screaming‐pink script set in an ambience of blue billows.”

Other publications, like the New York Daily News, questioned why writing was being brought indoors in the first place.

“What am I doing in this art gallery’s steambath atmosphere looking at yards of names like PHASE II and FLINT 707 when I have been saturated by miles of names like these every day on the summer steambath called the subway,” Ernest Leogrande wrote.

Despite his less than enthusiastic tone for much of the Daily News piece, Leogrande couldn’t help but conclude by stating, “Despite the negative associations, the graffiti makes dynamic pop art.”

Though UGA would splinter over the next couple of years, it had succeeded by at least raising such questions. It also opened up commercial possibilities as writers like PHASE 2 and many others would step partway or in full into studio practices — a dilemma that extends to the practitioners of today.

According to The New York Times, by the beginning of 1975, PHASE 2 had largely given up subway writing, moving his work onto paper and canvas or into sculpture. And he continued to develop new styles, sometimes passing them off to his fellow writers.

“PHASE was a man of great integrity, and a guy who had been confronted with many, many opportunities to compromise himself and his art and his worldview for the sake of notoriety, fame, money,” Mansbach says. “And he consistently went his own way. He was a visionary guy.”

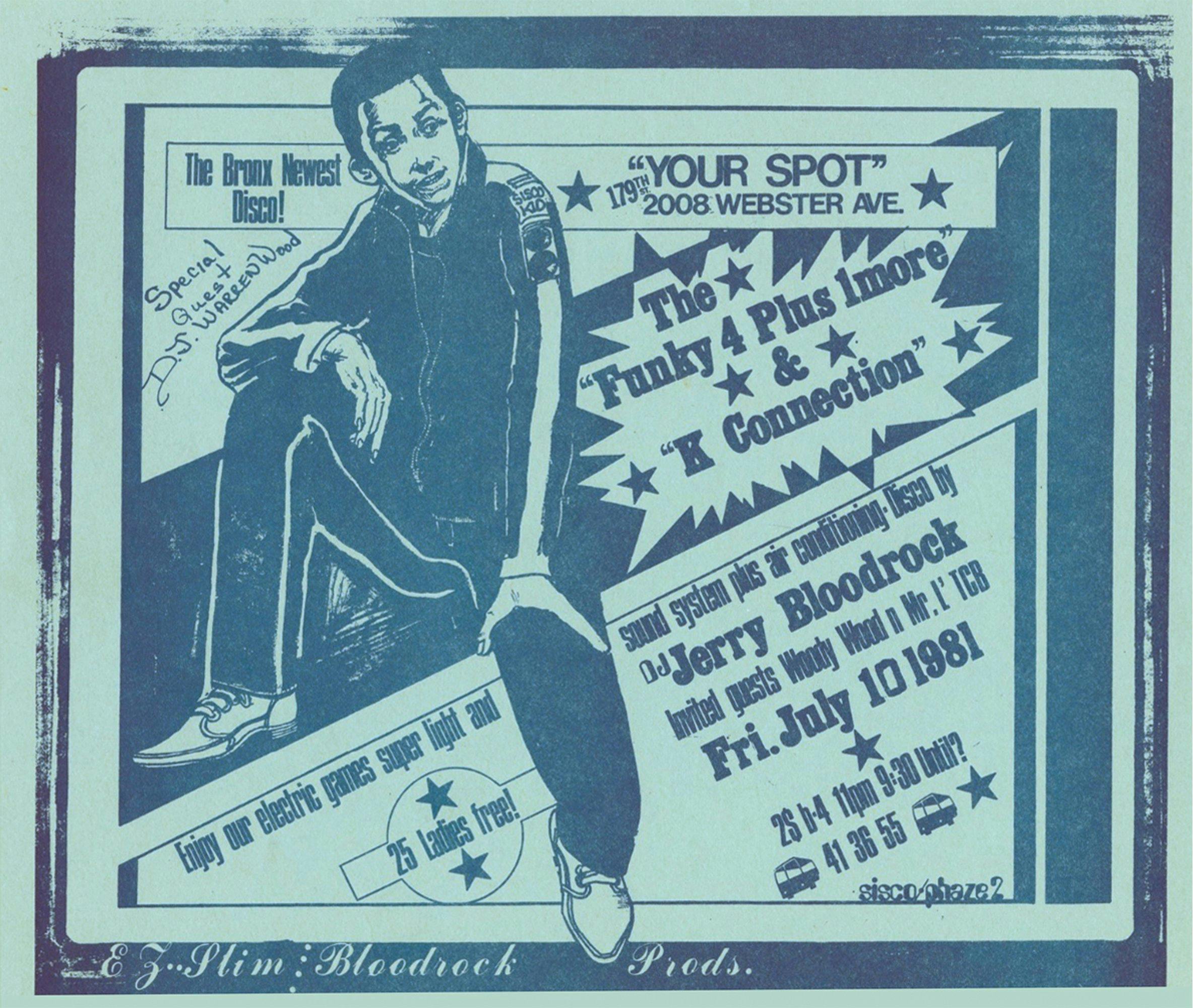

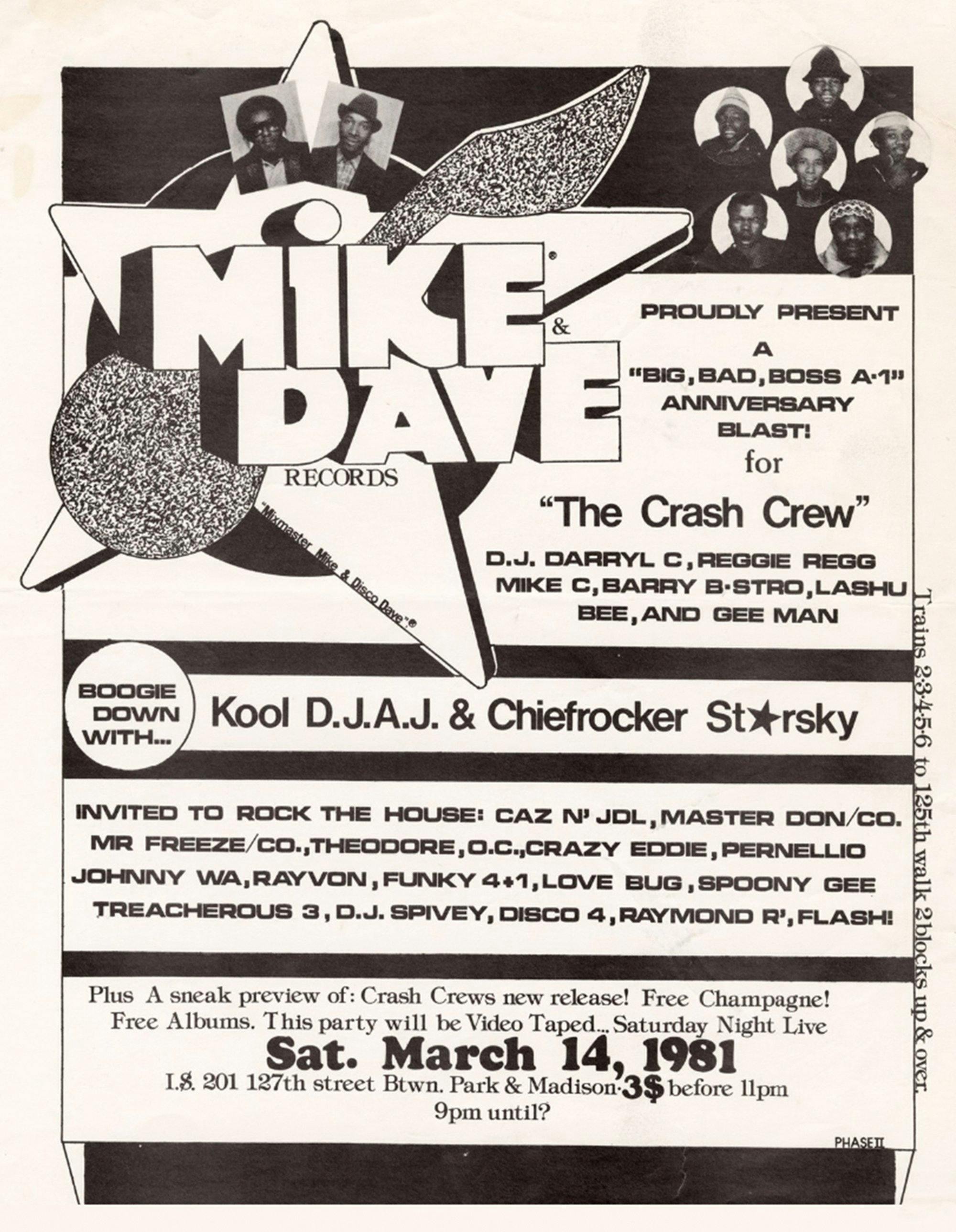

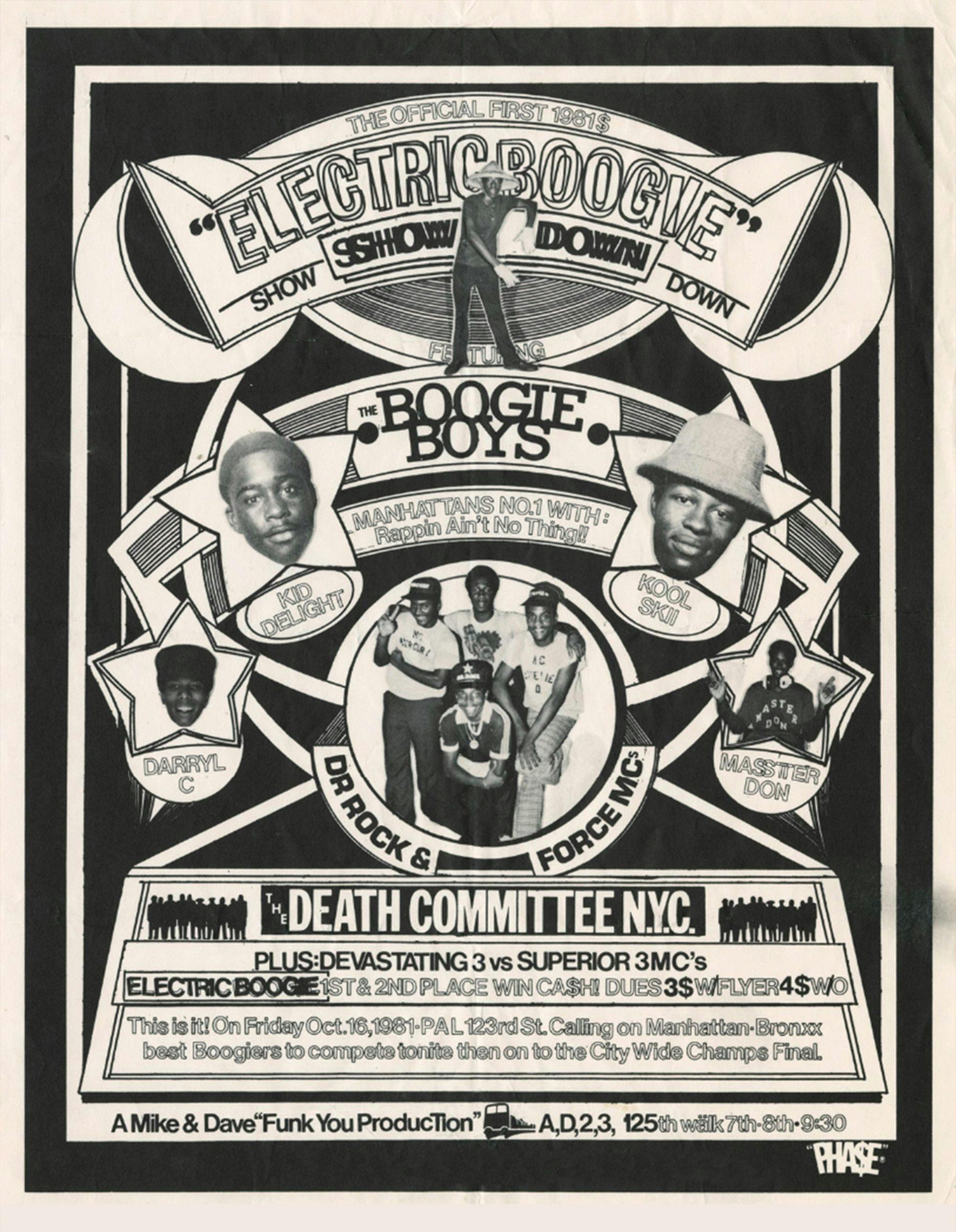

PHASE 2 FLYER

Entry into Hip-Hop

Early writers pre-dated Hip-Hop music. Would-be masters were raised on popular music of the era like rock and roll, funk, R&B, and disco, often channeling the rebelliousness they heard on record into bombing missions. As musicians got bigger and bolder with their own sounds, so too would writers seek out more grandiose styles.

PHASE 2 was someone who zigged when others zagged. As a result, he was one of but a handful of writers from that first generation who actually dipped their toes into Hip-Hop culture — both as a graphic designer connecting the colorful handstyles and bubble letters on walls and trains with the new sound of the streets, and as an actual musical talent as well.

“According to PHASE, he was DJing before Kool Herc,” Mansbach explains. “Not publicly, but just doing his own thing on reel to reel.”

In 1978, PHASE turned his artistic skill to party flyers. Artists like himself, Buddy Esquire, Sisco Kid, Eddie Ed, Anthony Riley, Brian Hicks, and Danny T. Riley were the main connection between Hip-Hop music and graphic design.

PHASE 2 helped elevate the aesthetic. He took the low-fi, photocopied flyers made from Letraset, markers, cut-up photographs, and glue and added personal homages to art deco, Jack Kirby comic books, Romare Bearden paintings, and manga. The result was lasting pieces of art for Hip-Hop pioneers like Grandmaster Flash, Grand Wizard Theodore, Soul Sonic Force, Funky 4 + 1, and Afrika Bambaataa.

“When I went to Grandmaster Flash’s manager to suggest making flyers to advertise their jams, there really wasn’t anything like that happening, and that’s why I suggested it,” PHASE 2 told Eye on Design. “What you did have were big Merengue posters by Salsa Kenny and Izzy Sanabria, but we weren’t really promoting jams on any real level like that. I thought that it made sense to, so I started doing flyers for Flash, and then the wave came behind it.”

The process was relatively the same each time. PHASE 2 considered the number of acts on the bill, which would inform the typeface, font size, and how many photographs to use. The result was something distinctly his own — “Funky Nous Deco” is what he called it — with personal touches like Chartpak markers, jumping letters, doubled words, stars, circles, squares, and figures portrayed in silhouette.

PHASE 2 FLYER

“We could, in effect, make mediocre talent seem like superstars just by manipulating words, using photos, and presenting it extravagantly,” he wrote in the November 1993 issue of The Source.

PHASE 2 furthered the culture by making logos for Cash Crew and Tuff City Records, as well as the poster for 1982’s New York City Rap Tour. The latter was a pivotal moment in Hip-Hop that saw the Rock Steady Crew, the Dark and Lovely Double Dutch Girls, Grandmixer DXT, Afrika Bambaataa, FAB 5 FREDDY, the Infinity Rappers, FUTURA, DONDI, RAMMELLZEE, TAKE 1, and Little Norman travel to England and France, providing the culture its first international exposure.

"PHASE 2 comes along," FAB 5 FREDDY says. "We rhyme. We graffiti. We break dance. All this shit is going on stage simultaneously like a fucking wild free-for-all. We don't think anybody is going to understand it — because nobody has heard anything about rap — but fucking people love it. That plants the seeds of Hip-Hop in France, which has remained the second biggest market to this day."

By 1981 PHASE was using multiple styles and estimated that he was producing 75 percent of all the Hip-Hop flyers in circulation in New York City at the time.

“He said the feeling of [making a flyer] was like you’re almost an addict to drugs,” says Pete Nice, one third of the Hip-Hop group 3rd Bass.

“One guy said that he would go to his crib, see his mom, and he would be working on a flyer. They’d go out to play ball in the park and come back and eight hours later he’d still be there working on the flyers.”

While PHASE 2 will be best remembered for his visual contributions to Hip-Hop, he was one of the few writers to cut an his own rap record. He met Aaron Fuchs, owner of Tuff City, while the record executive was working on a record with Barry Michael Cooper (who would go on to write the screenplays for New Jack City, Sugar Hill, and Above the Rim). Fuchs suggested that PHASE 2 should contribute a rap verse. He agreed and they recorded a song called “Beach Boy” under the moniker “Verticle Lines.”

The fact that PHASE was down to record a verse doesn’t surprise Mansbach. Since he moved seamlessly between the Uptown and Downtown crowds, it was a skill that PHASE 2 simply picked up along the way.

“When someone was like, ‘You should rhyme’ or ‘Can you rhyme?’ He was like, ‘Of course I can rhyme. That’s like asking if you can breathe air,’” Mansbach says. “Just like every kid in New York had a tag — whether they were skilled or not — everybody who was down had a rhyme, at the very least.”

PHASE 2 followed up that project with “The Roxy,” a collaboration between him and experimental punk-jazz-funk group Material that honored the historic New York City venue. While the record wouldn’t receive major acclaim, PHASE 2 contributed to the cultural revolution simultaneously occurring in 1982 that included “Planet Rock” by Afrika Bambaataa & the Soul Sonic Force and “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five.

There are also persistent rumors that PHASE recorded other material under the moniker “Fabulous Phazio” with a group called the Wicked Wizards. For those who knew PHASE for decades, his love for Hip-Hop was consistent.

“I saw it early in his life and I saw it later in his life,” COCO 144 says. “It was what he lived for.”

PHASE 2 / PHOTO: COCO 144

‘Wild Style’

In 1979, filmmaker Charlie Ahearn released an unlikely take on the kung-fu genre. He shot The Deadly Art of Survival on Super-8 film and cast untrained actors in all of the major roles. During filming on the Lower East Side, Ahearn witnessed firsthand the artistic merit of writers like LEE, who was continually pushing the boundaries on mural painting. As fate would have it, Ahearn’s interest in using unseasoned actors — and his interest in writing culture — would go a long way in bringing Hip-Hop culture to a worldwide audience.

At the same time, FAB 5 FREDDY was considering how he could further legitimize the burgeoning graffiti movement. As an avid reader — with a particular interest in art history — he understood that for something to be "culturally complete" — it need to coalesce with other elements.

"There needs to be music, a visual art, and a form of dance," FAB 5 FREDDY says. "I thought, 'Wait a minute. Well, the graffiti is the visual art. This budding rap music and DJ'ing is a form of music, and this breaking is dance.' I thought, 'Wow, these things are united.' Then I said, 'Maybe the best way to get this narrative out would be to make a movie. We could tie this all up together and create a narrative that makes this real.'”

Like Ahearn, FAB was equally enamored by LEE's work. He made it a mission to track down the artist. FAB laughs as he recalls showing up to LEE's school. The legendary writer assumed he was a cop looking to arrest him.

"A big part of LEE's amazing run was never getting busted during the time when he was doing all those whole cars," FAB says. "Once he realized I wasn't a cop, I started sharing all these wild ideas and we became close friends."

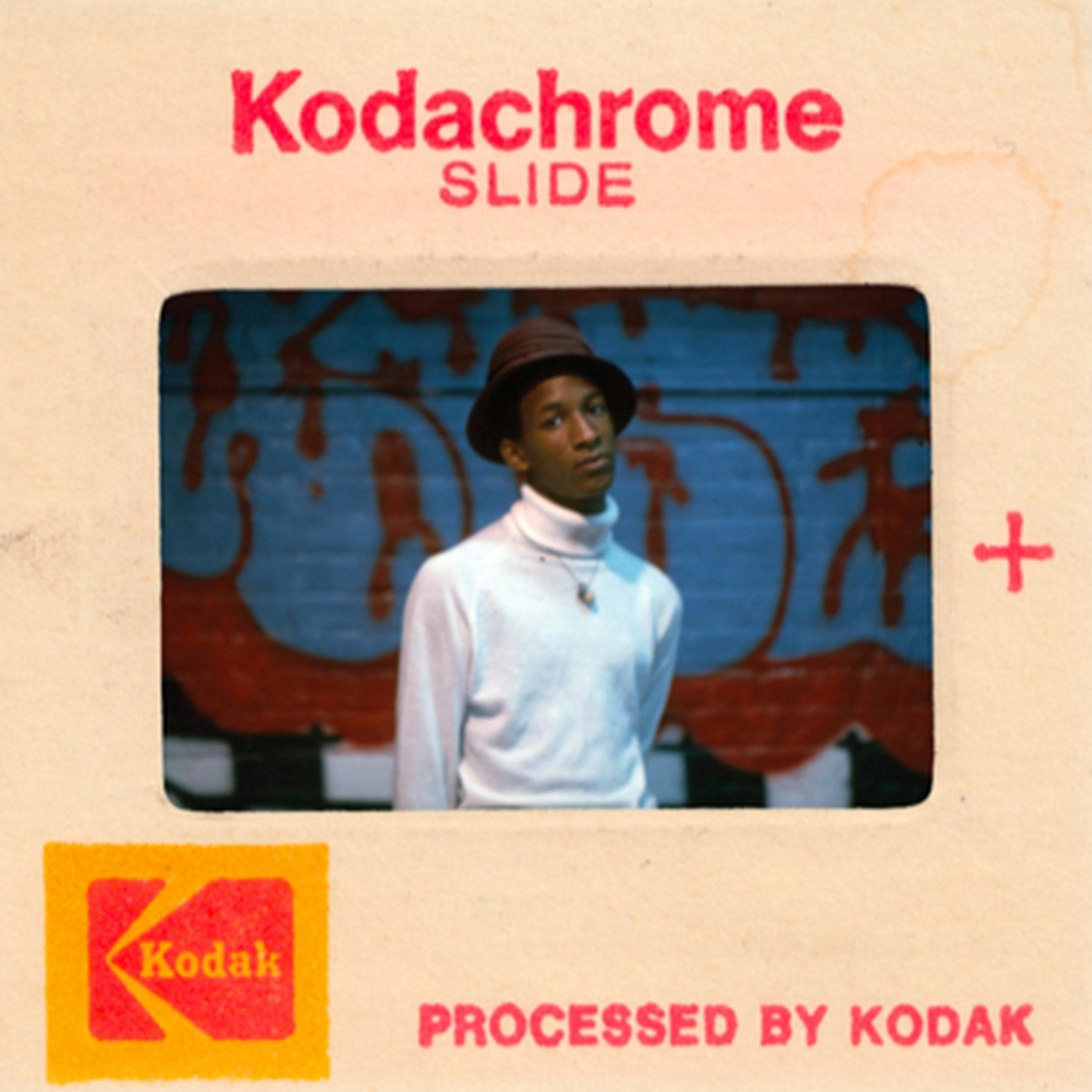

In subsequent months, Ahearn spent time inside the Ecstasy Garage Disco in the Bronx. He did photo slideshows while watching Hip-Hop performances by luminaries like Grand Wizard Theodore and Busy Bee. During one of Ahearn’s slideshows, PHASE 2 approached him with three different slides; a car, a train with bubble letters, and a picture of him posing at the Razor Gallery. Like so many others, Ahearn was drawn to PHASE’s energy and art — likening his style to one of the most recognizable artists of all time.

“PHASE 2 had this thing that reminded me of Picasso circa 1910-1911."

- Charlie Ahearn

FAB had seen the posters for The Deadly Art of Survival and believed Ahearn would be the perfect director to bring to his film idea to life. Since FAB seamlessly moved between the Uptown and Downtown crowds, he found himself at the Times Square Show which boasted avant grade filmmakers, artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, and musicians. As fate would have it, Charlie Ahearn was also in attendance. FAB 5 FREDDY pitched him his idea. Ahearn was particularly struck not only by the possibility, but that FAB personally knew LEE.

Since PHASE 2 was widely known throughout the city, FAB imagined a prominent role for him in the film. They set a meeting. FAB's first impression was that PHASE 2 was relatively shy, and spoke in a low, whispery tone. Yet, he was the perfect embodiment of who they wanted for a character named "Phade."

Ultimately, PHASE 2 didn't appear in the film. But for FAB 5 FREDDY — who went on to play Phade — the homage to PHASE 2 is unmistakable.

"When me and Charlie were on one of our many research trips to the Bronx, I remember meeting him and his whole style is so dope," he says. "That became a big inspiration for my Phade character in Wild Style. As we got to know him, he was such a significant connection to everything that I had envisioned."Ultimately, Wild Style was instrumental in bridging the gap between writers from New York City and the rest of the world. Audiences felt like they were watching a documentary, not a fictional film.

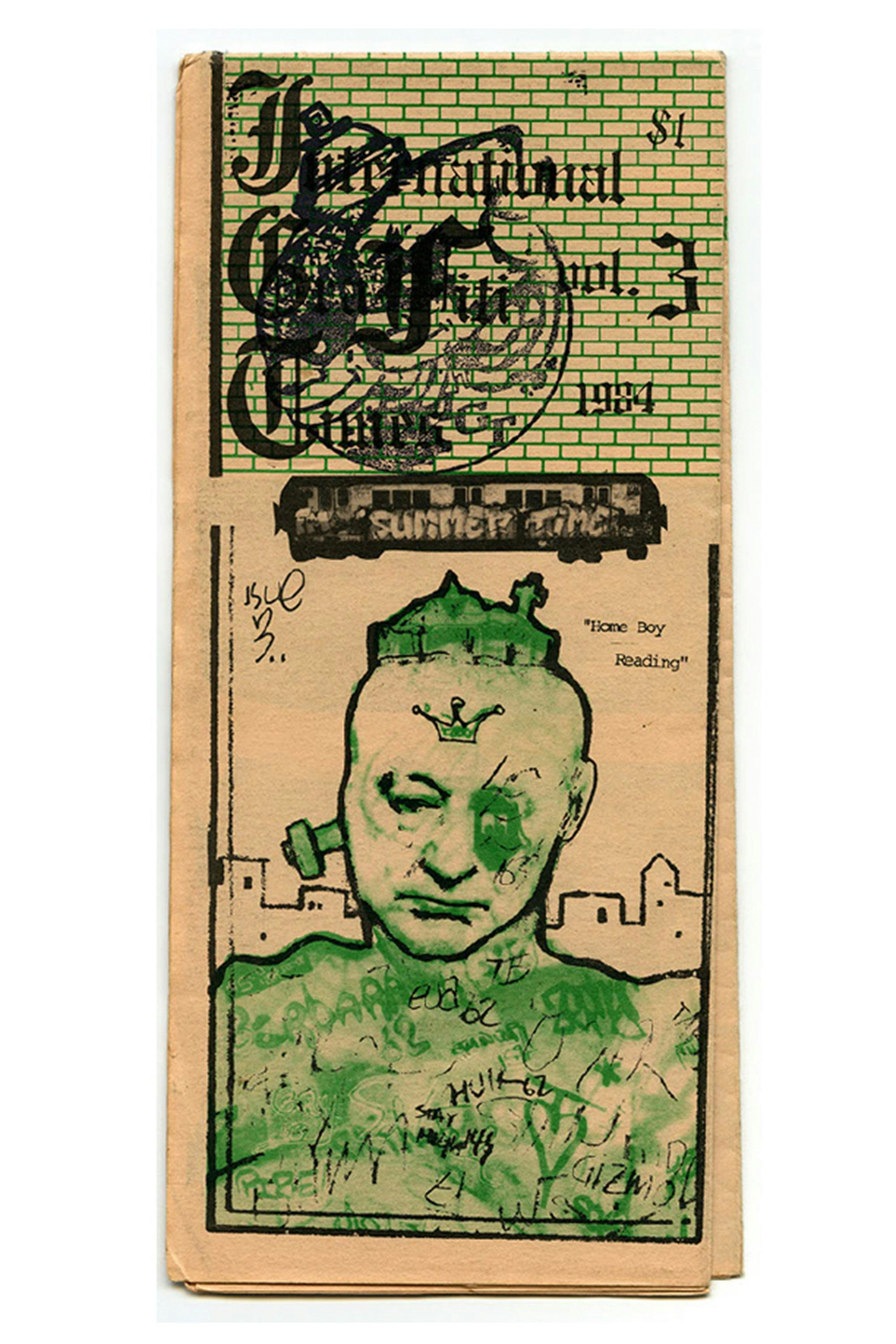

IGT NEWSPAPER

‘International Graffiti Times’ & the ‘G-Word’

In late 1983, downtown artist and photographer David Schmidlapp, who produced photomontages of street fashion for the style section of the Soho Weekly News, published the first issue of International Graffiti Times. The front cover of IGT’s first issue depicted an image of a bloated Mayor Ed Koch, the sworn enemy of graffiti, covered in tags.

Schmidlapp and PHASE 2 first met when the artist was interviewed for the second issue of the zine. Their lengthy chat spanned several pages and showcased PHASE 2’s unique viewpoint on not only art but life itself.

PHASE 2 eventually served as the publication’s art director from issue #8 in 1986 to its final issue, #15, in 1994. He introduced a cleaner and more legible design without undercutting its density and dynamism and expanded to include multi-page features (some printed in full color). A perfect example was the PHASE 2-crafted photomontage entitled “Renegade Culture/Situation Stylers,” which combined extreme detail and a tight page design.

“IG Times was an incredible undertaking that he and Schmidlapp put together,” Mansbach says. “It changed format over the years, but for most of its run it was a broadsheet — like the size of The New York Times. You could fold it out, take it apart, and it was this incredible mix of art and journalism written by PHASE on whatever struck his fancy. A lot of this [was] historical record correcting and not of just essays and treatises on the nature of rap, of Hip-Hop. That print run is really, really significant. And what do they say? Velvet Underground only sold 10,000 records, but everybody who bought one started a band? IG Times was a little bit like that. The DNA of IG Times really worked its way into all of the underground magazines of the mid ’90s, which was a really fruitful time for independent Hip-Hop journalism.”

Even before IGT started, PHASE 2 was contemplating the so-called “G-word.” He wholeheartedly rejected the idea that the word “graffiti” captured the spirit of what “writers” like him and his peers were doing. In fact, if a journalist used that word during an interview, PHASE 2 would just hang up the phone.

“PHASE 2 and anybody associated with him won’t have anything to do with you,” VULCAN says. “You’re not going to interview him. You’re not going to write about him. He’s not going to talk to you. You’re a dumbass. That’s how it is. You could be writing for 30 years, but if you’re saying that word, you’re a dumbass.”

Many early writers like PHASE 2 and VULCAN attribute the usage of the offending term to Richard Goldstein’s March 1973 piece in New York magazine called “The Graffiti ‘Hit’ Parade.”

Although Goldstein’s piece was complimentary of what was occurring at the time, Mayor John Lindsay was simultaneously on the warpath against a whole community he classified simply as “vandals.” As a result, writers like VULCAN and COCO 144 believe that the G-word is one laced with negative connotations.

“How can this word define these beautiful murals on the sides of trains and on handball courts and still mean the same thing as a scribble in a bathroom stall?” VULCAN asks. “How could that be the same word? There needs to be a different word, if you accept the word.”

For many of the early generation of writers, there was no room to compromise — even if that meant losing out on the connection between the streets and the lucrative mainstream art world.

“Saying the G-word is like saying the N-word,” VULCAN says. “That’s basically it.”

PHASE 2 never softened on his interpretation of the G-word — a view that lifelong friend COCO 144 has tried his best to carry forward, even though it hasn’t been easy. For them, “writing” meant “aerosol art.” But for the rest of the world, they couldn’t understand why the G-word was something that wasn’t complimentary or descriptive of the movement.

“It was sort of like a slave mentality — to label or call ourselves something that was given to us by the media,” COCO 144 says.

‘Stress’ and ‘Elementary’

PHASE 2 / PHOTO: MICHAEL LAWRENCE & HERBERT MIGDOLL

Alan Ket was still in high school when he began contributing to International Graffiti Times — which eventually rebranded to just IGT as a result of PHASE 2’s mission to remove the G-word from the conversation completely. As an impressionable kid, Ket witnessed firsthand PHASE’s brilliance on the printed page. When he launched his own project, Stress Magazine, in 1995, he knew he had to get PHASE 2 involved.

“I invited him to be a columnist,” says Ket, who would go on to found the Museum of Graffiti in Miami. “He contributed to every issue.”

Unbeknownst to Ket at the time, PHASE 2 refused to have his work edited. It wasn’t that he had a distrust of his colleagues. Rather, he often found that journalists took his words out of context. A PHASE 2 column always ran just as he wrote it.

“He understood the power of words,” Ket says. “He understood how to position himself, and he understood how to be a protector of culture.”

At that point in his career, PHASE 2 had become something of an international man of mystery. He had traveled the world several times over and earned a reputation among serious art collectors in Italy, the Netherlands, and Japan. Whereas stateside people may have thought that he was unmotivated when it came to his studio practice, Ket is adamant that he was very active in Europe.

“He was making art and participating in things, but they were very much in Italy alone,” he says. “He was also writing for an Italian Hip-Hop magazine in the ’90s. So he was active with Hip-Hop culture. I have tons and tons of his writing exclusively in the ’90s where he’s talking about Hip-Hop culture, b-boy culture, rap, aerosol art, and all that stuff. He was fully invested in it and very passionate about it.”

Since he and PHASE 2 were friends, Ket was one of only a handful of people who had access to PHASE’s fine art practice at the time. Ket described the work as very “geometric” in nature, looking as if it could have been made in a future in which the cosmos and Wild Style graffiti collided.

“There was a mix of organic-like, creature-looking stuff,” Ket says. “He loved Japanese culture. Particularly all that monster and robot stuff. Some of his stuff looked like it belonged in that world.”

Adam Mansbach was another person who had a strong — albeit unique — working relationship with PHASE 2. In the ’90s, Mansbach and Ket partnered on a Hip-Hop magazine called Elementary. Their goal was to add more journalistic and long-form qualities to a format that had primarily been defined by shorter “bursts” by contributors.

While PHASE 2 had certainly established a precedent when it came to his own writing, Mansbach was the rare creative who was allowed to edit his work.

“PHASE was an uncompromising guy when it came to telling the truth as he saw it about the culture and all threats — internal and external — to it,” Mansbach says.

“I was a fiction writer. I was somebody with a kind of journalistic background coming in. And I think Alan thought that maybe PHASE would let me edit him, and for whatever reason, that turned out to be true. It largely consisted of me being like, ‘PHASE, my man. What you’re saying is 100 percent right on, accurate, completely perfect. Could you, however, not say it in all capital letters?”

Their relationship grew from one centered on work to an actual friendship. He and Mansbach would have long conversations on the phone. Mansbach vividly recalls discussions about people taking ownership over styles of lettering PHASE thought he invented, the complicated history of WRITERS CORNER 188, and things that happened to him as far back as 1973. He would go over to PHASE’s house and watch him meticulously craft collages for hours on end with scissors and glue. For him, it was but another facet of the artistry that PHASE 2 possessed beyond putting paint on canvases.

The Guernsey Auction

In 2000, the first major auction dedicated to writing occurred in New York City at Guernsey’s Auction House — an institution best known for selling Rembrandts, Renoirs, and a $3 million baseball. The collection featured everything from canvases, sculptures, and subway signs to the actual doors from the 51X Gallery on St. Marks Place — a locale that became famous between 1979 and 1984 as a meeting place for artists.

“It’s an extraordinary range of material, said Arlan Ettinger, president of Guernsey, when speaking with the New York Daily News. “We’ve been told that we’ve assembled 90 percent of the major names in graffiti art.”

Those names included Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, LEE, TAKI 183, DONDI, CRASH, TRACY 168, BAMA, COCO 144, DAZE, and PHASE 2. The latter’s collaboration with Douglas Abdell — a sculptural depiction of the letter “A” — was expected to go for at least $250,000.

In addition to the sculpture, PHASE 2 was selling pieces from ’81, ’82, and ’93 for $3,000-$4,000. The general consensus among critics was that graffiti was the last great art form of the 20th century.

“He wasn’t represented by a gallery up until recently,” Ket says. “You can’t just find his work — like it’s fairly impossible to find. You really have to do detective work to find out who might have owned it.”

Ket’s museum in Miami boasts a number of artifacts from the late artist, ranging from skate decks to end-to-end burners across the walls. It represents work from the ’70s into the 2000s. He says PHASE 2’s artwork remains very collectible to this day. But the real challenge remains discovering where it is, who has it, and dealing with the hefty price tag. The curator is adamant that despite his work being coveted, he never wanted the fame or infamy of artists who successfully transitioned from the street to galleries, like Banksy or KAWS. Rather, he wanted to let the work speak for itself. As people peruse the museum, they’re left with a quote from PHASE 2: “We created an art form that came from the letter.”

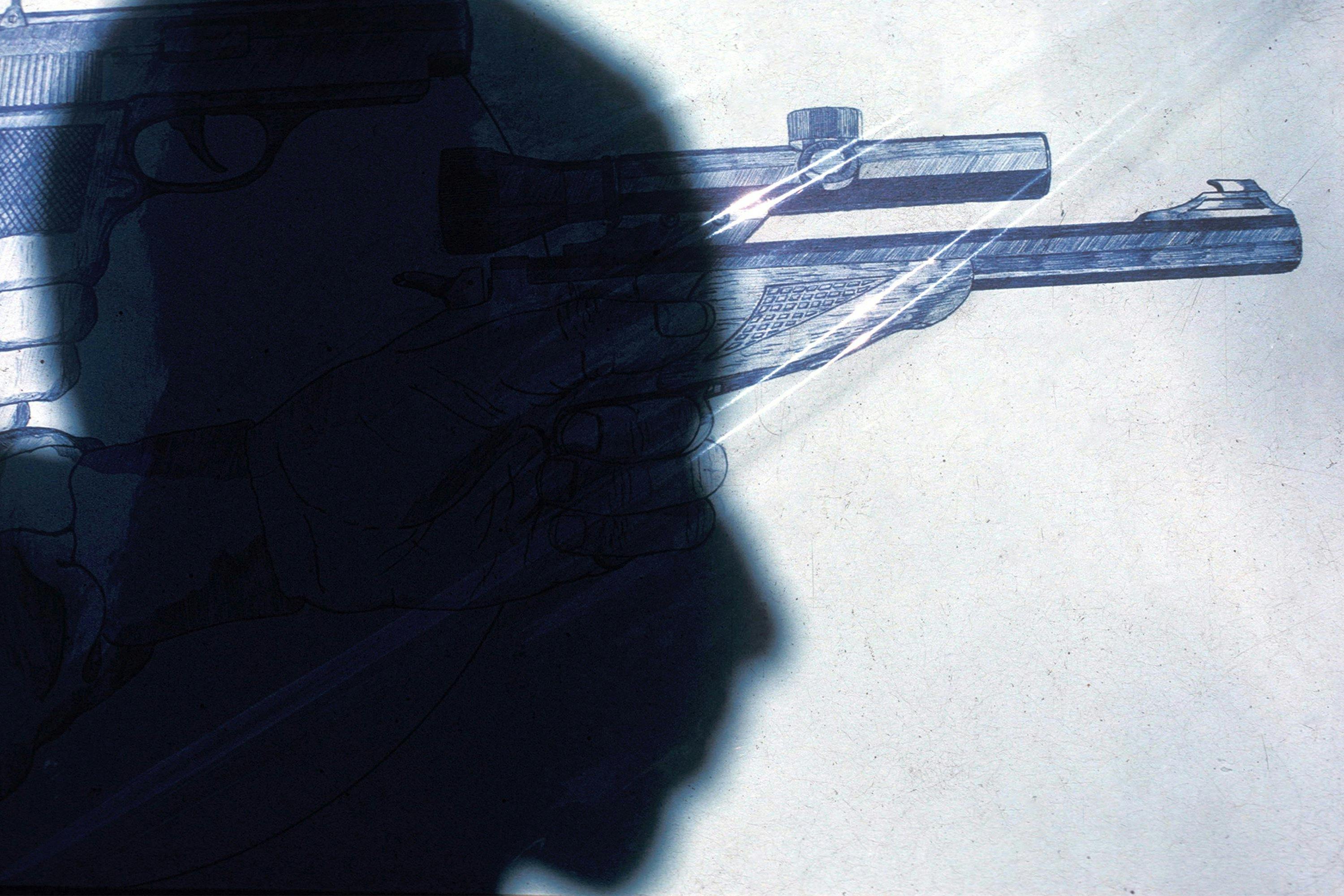

PHASE 2 GUN / PHOTO: COCO 144

Going International

While the American audience has certainly accepted the legitimacy of writing as an art form — strengthened by Roger Gastman’s recent bicoastal exhibition, “Beyond the Streets” (2018-2019) — it was a long and winding road to get there.

In Europe, audiences were more accepting — aided by the impact of Hip-Hop-centric films like Style Wars, Beat Street, and Wild Style. As a result, they recognized the brilliance of someone like PHASE 2 before he was truly recognized for his skill on American soil.

“What we did in the early ’70s in New York was not celebrated like it was in Europe,” says COCO 144. “I sort of put it in the same category as the jazz and the blues. The jazz and blues wasn’t accepted widely in the States until it went to Europe, so I feel the same thing happened with the writing culture.”

Since New York was — and still is — the mecca of the culture, fans understood that PHASE 2 was there from the beginning and kept upping the ante on what was possible not only on the street but also in one’s studio practice.

“He never stopped painting,” Mansbach recalls. “He never stopped getting better and innovating and flexing. I’ve seen giant walls that he did just in one color or two colors. No real fills, just outlines. Just to kind of show how hard he could rock by giving himself those limitations. We have a tendency in this culture to kind of very tightly box in the period of someone’s innovations, but the truth is with a lot of great artists and musicians, they keep innovating beyond that little sliver that we grasped. Louis Armstrong is considered to be the great trumpet player of the ’20 and ’30s — he’s better at playing the trumpet in the ’50s. And by the same token, PHASE continued to evolve.”

COCO 144 recalls long conversations with PHASE when the artist was living in Europe. He jokes that they couldn’t just talk for 15 minutes and hang up. These were chats that lasted hours and hours and would leave his face sweaty in the place where the phone pressed up against his cheek. As PHASE became more internet savvy, long emails also began rolling in.

He visited his friend in Milan back in 2003. Although PHASE was treated like a “celebrity” by people on the streets, COCO says he always remained humble. He witnessed firsthand as PHASE was undergoing something of a metamorphosis with his fine art.

“It was extremely detailed and going into areas that I just did not understand,” COCO 144 admits. “One of the names I used to call him was ‘Mathematics’ — short for ‘True Mathematics.’ He was calculating things. I can’t even find the words for it. He was always building, calculating, and balancing things that geniuses do.”

Father and Friend

PHASE 2’s 32-year-old son Kay’aan has fond memories of his father. As a child growing up in New York City, he heard whispers about his legendary art career. He watched as PHASE left for international trips throughout Europe and Asia. Days later, the postcards would start arriving. Since he was so young, it was hard to see his father as anything beyond a traditional caregiver and provider. But as he got older, he gained a better understanding of PHASE’s place in Hip-Hop culture.

Kay’aan’s very existence is a testament to the strength of New York City writing culture throughout the ’70s and mid ’80s. His mother, S.PAT 169, and PHASE 2 met through their shared love of aerosol art.

They’d literally climb into the train yard together,”

- - Kay’aan

S.PAT 169 was one of a handful of early female writers to make an impact, along with BARBARA 61, EVA 62, MICHELLE 62, BARMAID 36, BIG BIRD 107, IRENE 159, TASH 2, T.T.SMOKIN 182, CHARMIN 65, STONEY, and GRAPE 1.

His mother shared stories with him about PHASE’s love of both art and Hip-Hop culture. His father would sit around the table armed with markers, rulers, and other tools necessary to make a flyer for a popular act.

“When Hip-Hop was first becoming a thing, he stayed up late at night doing it,” Kay’aan says.

Although PHASE 2 wasn’t always present as Kay’aan grew up, he was consistently in his life. When PHASE provided instruction — everything from how to hold a spray can to the insignificance of tags that served no real purpose — Kay’aan always hung on every word.

They loved venturing to Chinatown to eat at vegan restaurants. (PHASE 2 was a big proponent of eating healthy and was one of the only people he knew who was experimenting with a plant-based diet.) After dinner they’d check out the shops and storefronts, where PHASE would buy beads to make necklaces for his friends. These handmade pieces of jewelry became tactile reminders that PHASE 2 held you in high regard.

Chinatown also enriched their shared love of kung-fu films. The subtitled movies — popularized in Hip-Hop culture by the Wu-Tang Clan — were so important to PHASE 2 that he made these Chinese sequences part of his voicemail message in the early ’90s.

“He was way ahead of his time with that,” Kay’aan says. “He loved Bruce Lee. You could see it in his art. Creative is not even the right word. He was on a different level. He’d always have his backpack and he’d be getting different little things — always from Chinatown.”

As Kay’aan got older, the postcards were replaced by long text messages, and from time to time, he might even be treated to his pop’s latest rap verse. As a burgeoning MC himself — operating under dual monikers Scama and Skmatik — Kay’aan thought about doing a mishmash of his father’s MC style with some more “contemporary” rhymes of his own. While these collaborations never came to fruition, the father-and-son tandem did create a painting together, which remains a tangible expression of their shared love of art.

Although PHASE 2 is a familiar name to fans of Hip-Hop culture, Kay’aan feels that the contemporary generation doesn’t fully understand his father’s contributions. He admits that, even within his own scope, PHASE 2’s career seems something of a mystery.

“People are going to read this story that don’t know about it,” he says. “They don’t know about him. Then they’ll spread the word, and it will keep my father’s legacy alive.

"He always gave me advice. I would always do my own thing. I’m not going to say rebellious, but I was defiant. I never really listened to anybody. He always instilled morals, values, and principles in me. He definitely taught me a lot.”

PHASE 2 FLYER

A Love of Flyers

In November 1993, three titans of Hip-Hop — Afrika Bambaataa, Grandmaster Flash, and DJ Kool Herc — graced the cover of The Source’s 50th issue. It was a celebration of Hip-Hop history and the “True School” individuals who helped take the culture from rec rooms and park jams to the heights we see today.

Nestled inside the issue was an essay by PHASE 2. While those who had the privilege of corresponding with the artist throughout his life often speak of his love of all-capital letters and a stream-of-consciousness style to his prose, PHASE’s thoughts were concise and easy to understand.

He questioned why the celebration of Hip-Hop never included “the fellas who stayed up until the wee hours knockin’ out flyers for ‘cat fronts’ and makin’ it possible for promoters to ‘hype’ their parties through our slick innovation?”

It was out of character for PHASE 2. Those around him spoke of his distaste for self-promotion. However, he wanted to make it clear to a specific audience — one that could support a publication wholly dedicated to its interest in Hip-Hop culture — that they needed to respect the foundation.

For PHASE, a “funky flyer” creatively supplied a fantasy for those who had attended a party, while also promoting an aura for those who had missed out. PHASE had been one of those young kids in 1972 when acts like Kool Herc and Gregory Disco Wiz rocked a party at the Hevalo. He recalled leaving the venue and receiving a flyer from an artist named Kareem, depicting Kool Herc pulling a rabbit out of a hat.

“The flyer is fresh, to the point, and unique,” PHASE 2 wrote.

These flyers were equal parts tactile memories and legit works of art. By 1981, he was a self-professed “flyer junky” who saw how his own work — and other notable flyers, like Buddy Esquire’s for the Breakout Jam and Sisco Kid’s work with DJ Charlie Chase — became as important as the music itself.

“Forget about the money, it was chump change,” he wrote. “You didn’t do all that work for the money. You did it for the results. That bottom line was knowing if a party was packed, you did your job. Whether the show was for yours or someone else’s, you knew what the motive was and just went with it. You ate and slept flyers; you couldn’t escape it. Don’t let anyone tell you — because they sure can’t tell me — one million hours and tons of flyers later that what we did wasn’t a part of this culture. I say this these guys had any sense, it would still be.”

As PHASE 2 got older, it became his mission to preserve the classic Hip-Hop flyers he made in the late ’70s and beyond. These pieces of paper — many of which were over 40 years old — pointed to specific moments in time during Hip-Hop’s formative years. While many historians see Kool Herc’s flyer for the inaugural Sedgwick Avenue party as the end-all be-all when it comes to matching a historical date with the ephemera to promote it, the works created by PHASE 2, Buddy Esquire, and Sisco Kid were equally important.

Others shared PHASE’s passion for preserving the key acts, venues, and artists who helped grow the culture — many of whom were inspired by his essay in The Source.

3rd Bass’s Pete Nice and Paradise Gray, a founding member of the X-Clan, had already spent ample time and effort preserving what was happening between 1983 and 1992 for a book project. After speaking on the phone, Nice and PHASE 2 had their first in-person meeting outside the New York City Public Library in the spring of 2017. These outdoor meetings throughout the city became regular rituals for the duo, and PHASE regularly brought a treasure trove of flyers with him.

“We just sat out there on a table looking at everything, and then I brought some stuff along too and I was fucking his head up with things that I had found through Sure Shot La Rock and other people,” Nice says.

They bonded over their shared love of flyers. This led to a formal agreement to move forward on a dedicated book project. Over the course of several years, Nice and PHASE 2 shared thousands of emails and texts. Individual archives were photographed and PHASE began the process of writing critical essays. In true PHASE fashion, they were mostly half-finished thoughts that aimed to set the record straight when it came to writing culture, flyers, and Hip-Hop in general.

“He’s probably the most integral Hip-Hop historian — or the earliest historian of Hip-Hop.”

- Pete Nice

Their conversations spanned several hours per phone call as they contemplated the arduous task of distilling an entire art form into several hundred pages. Although it was tedious work, both Nice and PHASE 2 reveled in the minutia — discovering classic flyers from other artists that had been pilfered from PHASE 2 originals he had forgotten about.

“There was this flyer that shows an ill, beautiful drawing of Dr. J with his Afro and he’s holding his hand up and he’s palming the ball and it was slammed, and it says ‘Slam Dunk Disco’ on top of it,” Nice says.“[PHASE] pulls out a 1979 Wicked Wizards flyer with the original drawing of Dr. J and it’s his drawing.”

Just as Nice and PHASE 2 were really starting to hit their groove, the artist’s voice weakened in tone, and he eventually stopped responding. Eventually, word reached him that PHASE had been seen out in public and looked visibly weak. When people asked him what was wrong, PHASE tried to pretend it was an all an act.

“He apparently lost the use of his writing hand — that’s why he couldn’t text,” Nice says. “That’s why he stopped emailing, and then just totally went incommunicado with everybody.”

Eventually, PHASE 2 responded via a WhatsApp message with a music video for the Double X Posse’s “Not Gonna Be Able to Do It.” As Nice looks back, he now recognizes that his friend was trying to tell him something that he couldn’t find the right words for.

Museum of the City of New York

When Martin Wong was diagnosed with AIDS in 1994, he made the decision to donate his entire collection of writing-culture ephemera to the Museum of the City of New York. This included more than 300 objects — including some 50 artists’ black books along with more than 100 canvases and over 150 works on paper — from luminaries like Basquiat, DAZE, FUTURA 2000, Keith Haring, and PHASE 2. At the time, the artwork by people who had been pioneers in the medium wasn’t necessarily collectible. Yet Wong had the foresight to compile the work, and the Museum of the City of New York gladly accepted it.

Wong ultimately succumbed to the complications of AIDS in 1999. He was 53-years-old. Friends, colleagues, and art enthusiasts gathered at the Museum of the City of New York for a memorial service, and to showcase a few of the pieces from Wong’s donated collection.

PHASE 2 was part of a panel discussion during the memorial. According to the hazy recollections of a few associates, PHASE was his truest self that day — verbally sparring with city officials about the merits of the art form itself.

While PHASE’s museum legacy is long and complicated, his connection to the Museum of the City of New York can’t be ignored.

Sean Corcoran, curator of prints and photographs at the museum, fell in love with writing culture as a young child. He fondly recalls going to Yankees games in the Bronx. When the home team was getting battered, he and his family left the games early, and he specifically looked forward to seeing all the colorful marks left behind on the 4 train. Years later, Corcoran would study art formally in college and landed a job at the museum in 2006. Like so many admirers of writing culture, he was enamored by Wong’s collection.

PHASE 2 had a reputation for finding you before you found him. Corcoran was of course aware of his work but was genuinely surprised when he received an all-caps email from the artist. Their bond was ultimately forged in an unlikely way over the next several months.

“It wasn’t about Hip-Hop and writing, it was about soul records from the ’60s and ’70s,” Corcoran says. “Even if we hadn’t talked for a while, every once in a while on my Facebook Messenger, some random YouTube video of a ’70 soul thing would just pop up.”

Corcoran was eventually invited to PHASE’s de facto office outside one of a number of vegan restaurants in Chinatown, like Buddha Bodai. The conversation rarely touched on aspects of his career. Both men were satisfied to talk soul records, or how Corcoran had named his son and daughter after Miles Davis and Mavis Staples, respectively.

Corcoran always knew that he wanted to do something with Martin Wong’s vast collection. In 2014, he formally presented “City as Canvas: Graffiti Art From the Martin Wong Collection,” which featured works between 1978 and 1994. PHASE 2 was well represented. Corcoran admits that people recognized his importance but may have been dissuaded from working with him because it wasn’t always easy.

“As somebody who is showing artists’ work all the time — particularly within this genre — I consider his work to be among the most important,” he says. "I don’t think he has shown as much as he deserved to be shown, for one reason. You have curators who would meet him and say, ‘Oh, he’s too demanding. He demands this and this and this.’ And frankly, for historians too, for somebody who is so rigorous about the way he’s written about, talked about, perceived, it would become a turnoff for people. They would say, ‘Well, I could do a great show by this other guy who frankly isn’t as important, but I can actually do it without too much resistance.”

PHASE 2 ORIGINAL SLIDE

Farewell

PHASE 2 passed away on December 12, 2019, after a lengthy battle with ALS. COCO 144 witnessed the devastating effects of the illness firsthand. He took solace in knowing that, although the disease had ravaged his body, his best friend of nearly 50 years was lucid enough to know that he was there by his side.

According to David Schmidlapp, only his immediate family and a couple of his closest friends saw him during his final days. He is hopeful that despite the challenges we now face as a society, he will never be forgotten.

"The ACA galleries were planning to have a solo PHASE 2 exhibition in March 2020," Schmidlapp says. "Though PHASE was as private about his illness as he was about his personal life, his demise came kinda sudden the last few months. When he lost movement in his right hand, he continued with his left until he couldn’t draw or write anymore."

Schmidlapp insists he is working with PHASE's heirs to sort out his business and to continue building on his legacy.

The formal services took place on December 20 at Barney T. McClanahan Funeral Home in New Rochelle, New York. What was supposed to be a small, intimate gathering grew in scale as writers heard the news and wanted to formally pay their respects to the icon.

“Everybody in the family shared something about him,” says COCO 144. “Then some of the people that knew him — or had some kind of upbringing with him — said some things. I decided not to say anything at all. I just sat back and just listened to everything. I was choked up, and I just felt that sometimes saying nothing says a lot more. I feel that as long as you got memories of people, they still live.”

* Banner Image: PHASE 2 / PHOTO: MICHAEL LAWRENCE & HERBERT MIGDOLL