“With my man Two-TECs to take over this projects/They call him Two-TECs, he tote two TECs/And when he start to bust, he like to ask, "Who's next?" - The Notorious B.I.G. "Everyday Struggle"

The Intrasec building was inconspicuous; grey, with no logo or company name, positioned on 30,000 square feet of factory space just off the Florida Turnpike.

Those driving passed saw a regular stream of about 50-60 people, most of whom were Cuban-Americans, or immigrants from other Latin American countries, coming in and out, as they hopefully made enough money to chase down the so-called "American Dream."

Inside, these same workers were also producing an American-made nightmare.

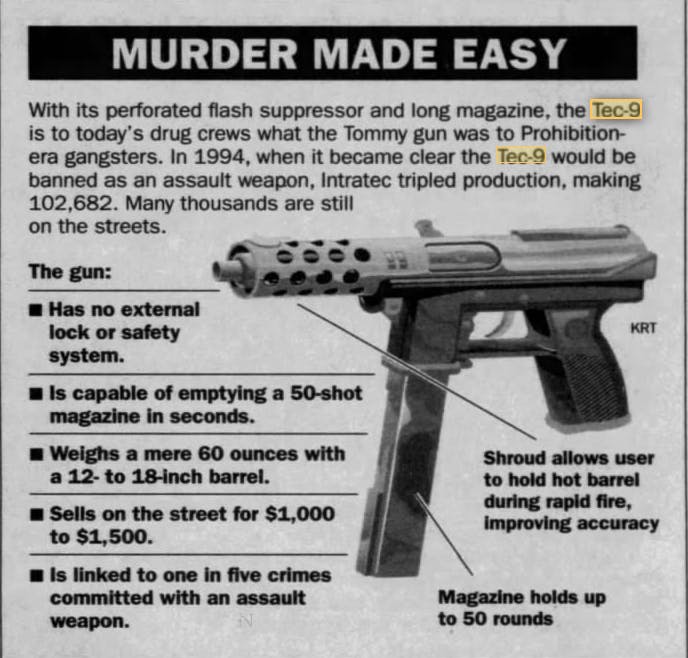

To a layperson, the weapon had a futuristic quality. It could be perceived as the type of gun a soldier of fortune from the future would use to exact revenge on a sadistic ruler from another planet. For gun enthusiasts, the real world applicable specifications — like 5-inch barrel, perforated flash suppressor, and 32-round magazine — me it yet another poster children for 2nd Amendment rights.

Retail price for the TEC-9: $210.

For years, big name companies like Colt Remington and Smith & Wessson — all located in Connecticut's "Gun Valley" — ruled the industry. By 1993, Florida was producing 80,000 firearms a year thanks to the rush on the TEC-9.

Intratec founder, Carlos Garcia, started producing the TEC-9 in the early 1980's when he acquired rights to the weapon’s design from a Swedish designer, George Kellgren, who had made improvements on a submachine gun originally designed for the South African government.

When South Africa decided that they didn't want to purchase his prototype, Kellgren turned to the only market that allowed civilians to purchase assault weapons: the good ole' USA.

Garcia, a Cuban immigrant, came to the United States with his family in 1962. His father, Miguel, a grocer by trade, had stayed behind. Like so many during Fidel Castro's stranglehold on the island, Miguel Garcia was imprisoned for three months, but after he was released, he was able to join his family in Miami.

To makes end meet, Miguel worked double shifts, and Carlos stood in traffic selling newspaper amongst the scent of diesel fuel and vaca frita.

The family's first-hand experience with tyranny would become a major rallying cry when both law enforcement, and politicians, criticized Carlos Garcia's weapon.

"As it happened in Cuba, as it happened in the Soviet Union, as it happened in China... it can happen here."

After a stint in the US Marine Corps, Carlos Garcia opened his first gun shop, Garica’s National Guns, in 1983 on SW 22nd Avenue in Little Havana in a store that had one time been Harold Goodman Furniture.

Garcia's National Guns was in a large, white building. Outside, a sign read, "Take your boy hunting. You'll never have to hunt for your boy." Inside, racks and racks of rifles lined the walls alongside shoebox-sized bins full of ammunition.

Garcia had no gun manufacturing experience, but he had a knack for marketing, and he liked the paramilitary look of the handgun Kellgren sketched.

Together, he and Kellgren formed Interdynamics Inc. — producing their handgun and selling it at Garcia's store. They called it the "KG-9." The K was for Kellgren, and the "G" was for Garcia — describing it as a weapon, "combining the high capacity and controlled firepower of the military submachine gun with the legal status and light weight of a handgun.''

While other companies touted their "Made in America" pedigree, Intratec were thrilled to announce a more regionally specific point of pride: "Made in Dade." However, the gun was notoriously inaccurate.

The KG-9 cost about $70 to produce because it only required a lathe and a vertical milling machine. Kellgren and Garcia were soon producing 100 guns a week.

The KG-9 was sold as a semiautomatic, firing one bullet with each squeeze of the trigger. But when federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms agents examined it, they found that the KG-9 could easily be converted to a submachine gun, shooting a stream of bullets with a single compression.

In 1982, under pressure from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, Kellgren and Garcia changed the KR-9 to make conversion harder. However, the new KG-99 came with an extended forward grip — advertised as an "assault grip" that let a shooter hold it with two hands and fire it like a machine gun. The ATF informed hem that thea assault grip was also illegal.

In 1984, Kellgren left the business, and Miguel Garcia joined his son in what was now a family business. Together, they renamed the corporation Intratec Firearms. Despite previous warnings from the ATF, father and son introduced a "Hell Fire" switch which gave users the ability to fire off 300 rounds in a minute. Carlos Garcia touted that his product was half the price of the next cheapest assault weapon.

"At two-thirds the weight ad price of an Uzi, the TEC-9 series clearly stands out among high capacity 9mm assault type pistols," magazine copy stated.

Business was good. From 1985-1988, Intratec produced almost 53,000 TEC-9's. Carlos Garcia owned a 14,516-square foot Mediterranean-style home in Coral Gables (assessed for $2.9 million), leased a fleet of luxury cars, and owned two, 37-foot speed boats. However, his success was built upon a questionable foundation.

According to The Atlanta Journal Constitution, one out of every five assault guns traced to a crime in 1989 was a TEC-9. That same year, the Bureau of Tobacco Alcohol and Firearms revealed that they had received 694 police requests for traces — more than for any other gun. For context, the Bureau ran 448 for UZIs, and 485 for Mac-10's.

Garcia denied any responsibility for the perceived connection, telling The Palm Beach Post, "I know some of the guns going out of here end up killing people. But I'm not responsible for that. The ultimate user is you the public. It is up to you how responsible you are in using that firearm, your car or what have you."

That February, a TEC-9 was used to kill Broward Sheriff's deputy Jack Greeney, who was trying to stop an in-progress robbery at Church's Fried Chicken. When one of the suspects, Lancelot Armstrong, was apprehended, he still had the sales receipt for the gun in his pocket. When he had purchased the TEC-9, he was wanted in Massachusetts on two counts of assault with intent to commit murder.

Despite Garcia’s insistence that the TEC-9 was intended to end up in the hands of law-abiding citizens, Intrasec's advertising, instead, suggested that they were speaking to a criminally-inclined user.

Its sales brochures stated that various models of its weapons were made with "Tec-Kote,” a special finish that, "provides a natural lubricity to increase bullet velocities" and, "excellent resistance to fingerprints."

The company produced more than 14,000 TEC-9 pistols in 1991 — a 700 percent increase from the previous year. By 1992, 99 percent of the guns on New York City streets originated from out of state. Florida alone was responsible for 35 percent. Intrasec's TEC-9 often sold on the black market for 300 times the sticker price at a time when a kilo of heroin went for just 10x.

"The Tec-9 is the weapon of preference for drug dealers here in New York City," said Lieutenant Kenneth McCann, co-commander of the New York Police Department's Joint Firearms Task Force. "It gives the impression of being a fully automatic Uzi or machine gun, and that's the way it is interpreted on the street. We're coming across them more and more frequently."

A series of drug-related murders in Washington DC in 1992 led to renewed scrutiny on the TEC-9. Lawmakers argued that the gun was, "Abnormally and unreasonably dangerous and pose risks to citizens of and visitors to the district." Garcia responded by renaming the TEC-9 the TEC-DC9. He later testified that the "DC" stood for "Defensive Carry."

36,000 more guns were sold.

On November 17, 1993, the Senate voted to ban the manufacture of 19 types of assault weapons, but allowed sellers to distribute guns that had already been made. This included Intratec's TEC-9, the AK-47, Striker-12, the Beretta AR-70, and the TEC-DC9. It would also prohibit copy cat guns of copies of the 19 weapons to prevent manufacturers from skirting the ban by making slight modifications and changing the product's name.

Florida senators split on he ban; Democract Bob Graham was for it, and Republican Connie Mack was against. For Democrats, it was the biggest victory since congress banned mail-order sales of rifles after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Senatory Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated in 1968. The 10-year ban was passed by the US Congress on September 13, 1994.

Not surprisingly, the TEC-9’s pervasiveness in culture began showing up in Hip-Hop. The gun was famously name checked on songs like “C.R.E.A.M.,” “Flava in Your Ear (Remix), “Da Graveyard,” “Natural Born Killaz,” “Buckin’ Em Down,” “Tonight’s Da Night,” and many more. In a genre where authenticity was paramount, specificity was a wordsmiths most potent weapon. In many ways, Hip-Hop songs served as free marketing for Carlos Gacia’s gun.

There was a small pushback from radio and print in regards to the reference. For example, in 1993, WBLS in New York instituted a policy against any lyrics they deemed advocated violence. Former Def Jam President, Bill Stephney, said at the time, “Filas went out of fashion. African medallions went out of fashion. And so will TEC-9’s and the TEC-9 will go out of fashion.”

In response to the congressional ban, Intrasec tripled production: making 102,682 models in a calendar year. It also stockpiled 50,000 magazines that could hold 32 bullets. Those, too, had also been banned.

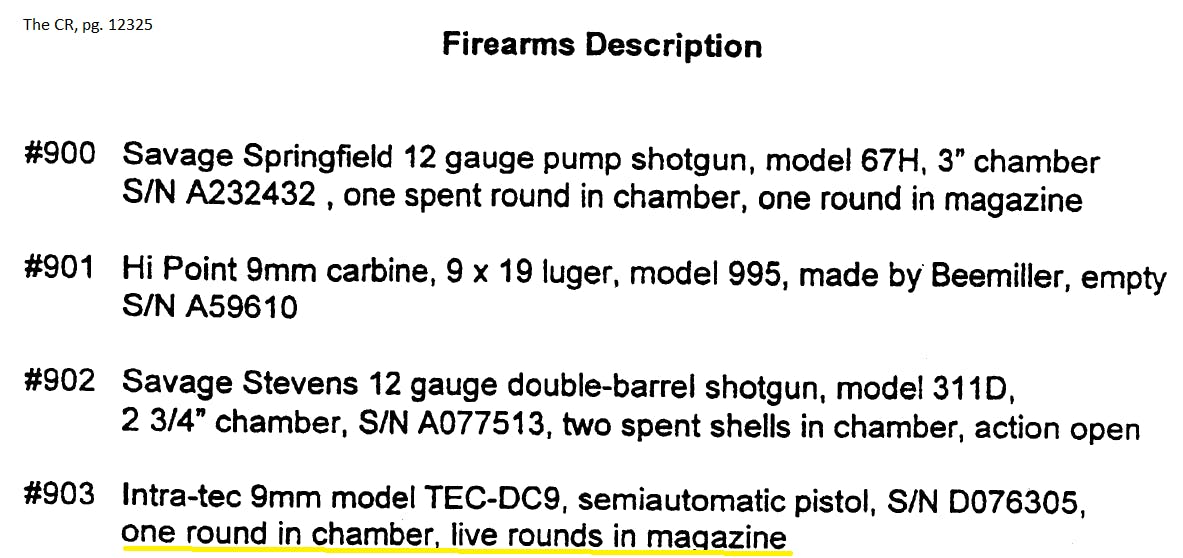

During this production flurry, model No. D076305 was created. The gun had several owners: Royce Spain, Larry Russell, Mark Manes, and finally, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, who would carry out the then largest school shooting in US history at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. 13 people were killed, and 20 people were wounded. Investigators said it could have been much worse, had Klebold’s TEC-DC9 not jammed during the slaughter.

Asked to comment of the school shooting by The Wall Street Journal, Garcia said, “I try not to follow the news.”

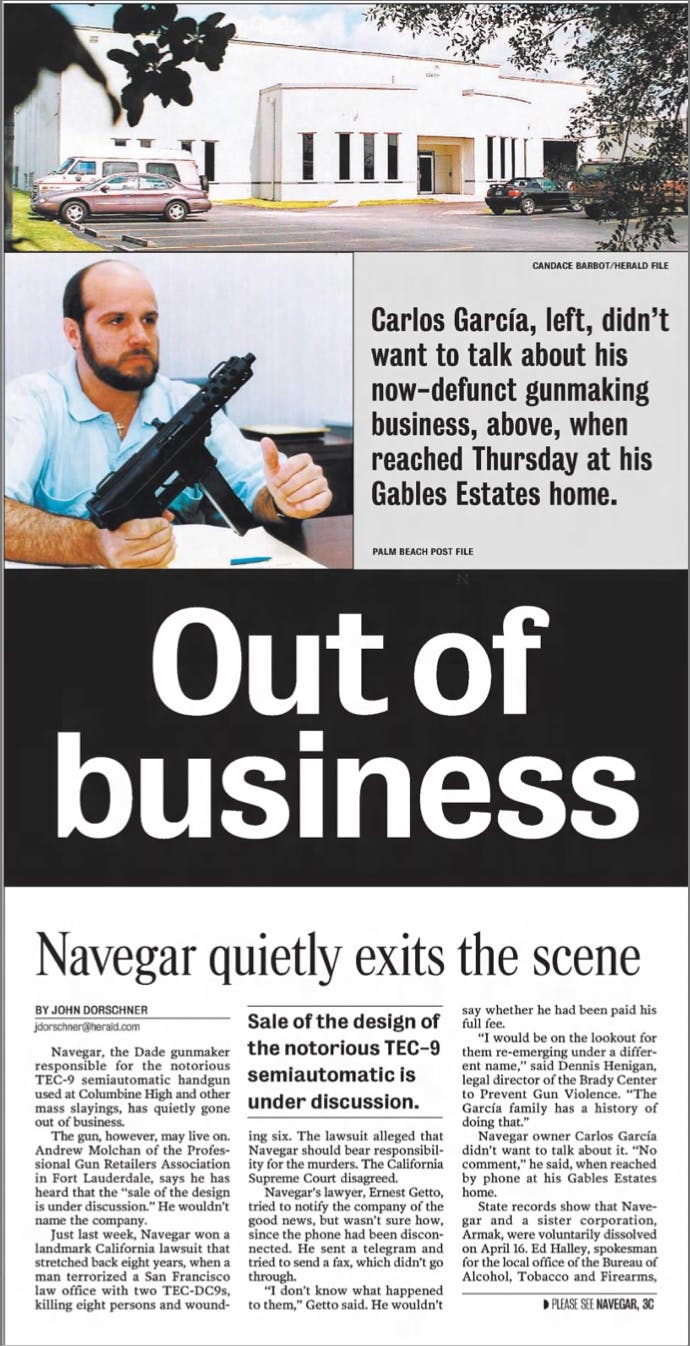

In April 2001, Navegar (what Instrasec rebranded to), went out of business. Experts theorized that the company had disbanded for two reasons: One, the expense it incurred as a result of the many lawsuits filed on behalf of victims hurt or injured by their products, and two, the Brady Act had banned features like the 32-bullet magazine, and threaded barrel that could accept a silencer. Simply put, the gun was no longer “fun enough” for enthusiasts.

"Its market was people like criminals and soldiers of fortune who wanted to fire a lot of rounds very fast," said Dennis Hennigan, legal director of the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence. "When they lost that capability, what did they have? A cheap, not very accurate gun."

Despite Navegar’s dissolution, the TEC-9 still has a consistent usage in contemporary Hip-Hop lyrics. It’s ironic, in many ways, because other proper nouns from the early ‘90s aren’t nearly as prevalent. Perhaps, it’s more reflective of the ongoing gun crimes in this country, than it is an affinity for the product itself.