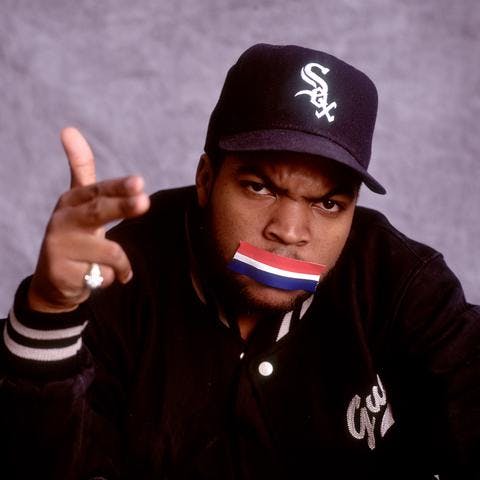

Credit to: Al Pereira/Getty Images/Michael Ochs Archives

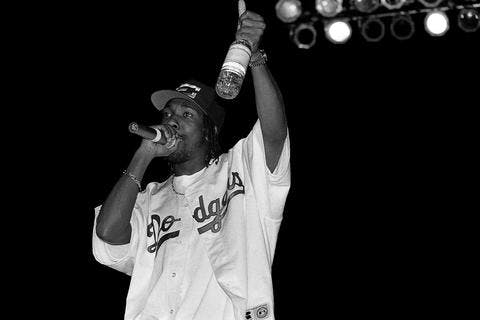

Credit to: Al Pereira/Getty Images/Michael Ochs Archives

A Brief History of Police Commentary Songs

Who Protects Us From You? A Brief History of Police Commentary Songs

By Soren Baker

Published Thu, September 17, 2020 at 10:00 AM EDT

N.W.A’s “Fuck Tha Police” shined a light on one of America’s ugliest and longest-festering injustices. Released in 1988, the seismic song helped expose how innocent young black men, in particular, were often being brutalized and harassed by racist police officers, many of whom were white. Although the song was released via a partnership between then-tiny independent labels Priority Records and Eazy-E’s Ruthless Records, the song quickly spread throughout the country.

“No matter where you were from in the United States, being black or Latino, that song magnified it,” Brooklyn, New York rapper O.C. says today. “It meant a lot for us.”

Since “Fuck Tha Police,” there has been an unrelenting cascade of high-profile incidents where unarmed black men and women have been killed or seriously wounded at the hands of the police. At the same time, rappers have released a cascade of songs addressing police brutality and bringing a steady stream of attention to this horrific phenomenon. In 1989, for instance, Boogie Down Productions released “Who Protects Us From You?” The Bronx-based group fronted by KRS-One highlighted the hypocrisy many police officers use while they say they are enforcing the law, when the bigger question of who protects the black community from the police is also raised.

Getting pulled over, harassed and arrested is the theme of LL Cool J’s 1989 cut “Illegal Search,” which initially appeared as the b-side of his smash single “Jingling Baby” and was subsequently included on his groundbreaking Mama Said Knock You Out album in 1990.

Back in California, Compton’s Most Wanted released in 1990 “One Time Gaffled Em Up,” a first-hand account of the harassment group members faced. The group called police “One Time” because it only took them one time to get you.

“It’s something that I wrote about at the time because it was something I was going through on a daily basis, or every two to three days,” Compton’s Most Wanted’s MC Eiht says today. “It was a conflict that we had growing up in the neighborhoods of Compton, Long Beach, Watts, LA. It didn’t matter the section. It was a county-wide thing. We never looked at it as anything that was out of the ordinary for those of us who grew in the neighborhoods. One Times gaffled. We dealt with it. They gang sweeped on Tuesdays. We dealt with it. They just patrolled the neighborhoods and if they felt like, ‘Hey, you don’t look right,’ you were going to jail that day. You’d spend the day in jail and they’d let you out 2, 3 o’clock in the morning. That’s what the song was based off of, the realism of what we had to go through every day of dealing with police harassment and racial profiling.”

The next year, Main Source’s “Just A Friendly Game Of Baseball” and Cypress Hill’s “Pigs” became two more significant tracks to call out unjust actions from police, while Ice Cube’s 1992 track “Who Got The Camera?” referenced the beating of unarmed black California motorist Rodney King, whose March 1991 beating was caught on camera by an onlooker and broadcast around the world, putting a magnifying glass on the police harassment that N.W.A, Boogie Down Productions, LL Cool J, Compton’s Most Wanted and others had been rapping about for years.

“The Rodney King [video] was the evolution of it,” O.C. says today. “Prior to that, it was seldom seen or seldom heard that you caught somebody on camera and exposed it. It’s being exposed and it’s still hard to convict these police officers. That’s scary, man.”

In 1993, KRS-One's timeless "Sound Of Da Police" likened the police officer to a descendent of the overseer on a plantation presiding over slaves, while O.C. portrayed the type of fear many people of color face when confronted by police on his 1994 song “Constables.”

“There’s nothing wrong with being fearful of something, especially if it’s unknown,” O.C. says today. “We know what harassment is, but we don’t know what death is and some of us don’t know what jail is. Some of us are not built for jail. Some of us are not built for things like that, so I think I spoke for people in general who get harassed by the police and are naturally afraid if you get caught walking up the block at night by yourself from the train stations. I used to walk from the train station. When I was a teenager, I was stopped a couple of times and was carded for my ID and I didn’t do anything wrong. That’s scary, especially as a teenager. But grown men get scared, too. We get afraid.”

The fear can go both ways. In 1998, Cypress Hill took a remarkable step with “Looking Through The Eye Of The Pig.” On this track, B-Real imagines what is it like being a police officer tasked with finding corpses at work and having to seriously consider whether or not he’s going to make it home to his wife and children. But the officer acknowledges that he’s worse than some of the people he locks up and his character spirals deeper into corruption as the song continues.

Even with these powerful songs, the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others at the hands and knees of the police continues. For their parts, rappers have continued sounding the alarm. In 2014, Vince Staples released “Hands Up,” a blistering track from his Hell Can Wait EP that voiced many of the same concerns, frustrations and outrage that N.W.A, Boogie Down Productions, LL Cool J, Compton’s Most Wanted, and others articulated in the late 1980s and 1990s.

“There’s been no change if you’re somebody like me who dealt with that on the regular,” MC Eiht says today. “It’s not as shocking anymore, unfortunately. Now that we see the videos, everybody can see how the black race is being stalked or killed or innocently shot by the police. It’s something that we’ve been going through forever. Even though now that everybody’s got video camera, camera phones, everybody is standing up for Black Lives Matter, it just goes to show that behind closed doors nothing really changes. People vote people in. We get new Presidents every four years, new Congress, new laws, new Senators and whatever, but behind closed doors and the reality in the neighborhoods and for the poverty-stricken people, nothing has changed in 30 years. This is stuff that I’ve been seeing since I was 12, 13 years old.”